Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

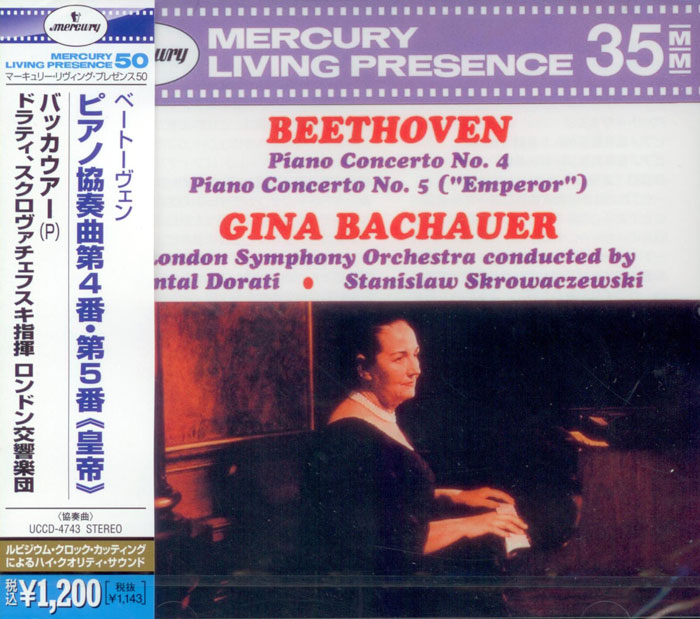

BEETHOVEN, Gina Bachauer, Antal Dorati, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski

Piano Concertos 4 and 5 'Emperor'

- Gina Bachauer - piano

- Antal Dorati - conductor

- Stanislaw Skrowaczewski - conductor

- The London Symphony Orchestra - orchestra

- BEETHOVEN

REWELACJA! 'The great Gina Bachauer was a magnificent pianist'

Płyta wyprodukowana z wykorzystaniem technologii Rubidium Clock Cutting, pozwalającej zdecydowanie odświeżyć, zrewitalizować i oczyścić nagranie!

RBCD jest w stanie - zdaniem niektórych melomanów - dorównać jakości dostępnej tylko dla płyt SACD.

*****************

The scope of her personality, the expanse of her transcendent musical expressiveness, the sheer magic of her presence, could never be adequately communicated by words of the page.

– Graham Wade, biographer

Gina Bachauer (1913-1976) was a Greek pianist often regarded as the greatest female pianist of the 20th century. A student of Cortot and Rachmaninoff, she enjoyed a long and successful performing career, and wooed the toughest of critics with her Romantic repertoire. She developed a close bond with the people of Utah and performed frequently with the Utah Symphony, even facilitating their first international tour. Due to this bond, her legacy lives on in Utah in the form of the Gina Bachauer Archives and the Gina Bachauer International Piano Foundation.

Gina Bachauer was born May 21, 1913 in Athens, Greece, of German and Austrian heritage. Young Gina’s interest in piano began at age 5 after attending a concert of Emil Sauer. Afterwards, she informed her parents that she wanted to be a pianist, and they eventually consented by furnishing her with lessons from a local teacher.

When young Gina was 9 years old, the Polish pianist Woldemar Freeman fell in love with Greece and settled in the country. Gina’s father took her to Woldemar to see if it was wise for her to continue to study the piano. “Freeman heard me play and said, ‘Yes, I will work with her,’” Mme. Bachauer recalled. “So I worked seriously with him, finishing my studies at the Athens Conservatory when I was 16 years old, winning the Gold Medal in 1929.”

“Because Woldemar Freeman, who had been a pupil of Busoni, had a German technique and approach, he wanted me to go to Paris to work with Cortot,” Mme. Bachauer said. “He wanted me to hear French music and to work with a master who was a great specialist of French music.” Her parents paid for her to attend the Ecole Normale de Musique in Paris, where she studied for 3 years under Alfred Cortot.

During her studies, she met Sergei Rachmaninoff, from whom she received virtually the only lessons he taught after his self-imposed exile from Russia. Regarding her illustrious teachers, Mme. Bachauer said:

“[Cortot] knew Ravel and Debussy and I think that no other pianist could have given me a better undemanding of their music, of their specific sounds. On the other hand, Rachmaninov was an amazing pianist, with superb hands, and an uncanny technique. He did not attempt to teach me, he was not really a teacher. If I asked him—and this happened very often—‘How do you do that passage?’ the answer was always the same. He sat at the piano, illustrating it, and saying: ‘Like that.’ He could not explain what he wanted me to do. He would always add: ‘Don’t try to copy what I am doing. You must try again and again until you find your own way of doing it. When you will show me what you want to do with that phrase and if you can convince me, then it is right.’ He made me realize that there are several ways to interpreting the same phrase, as long as it is convincing, as long as this comes from one’s own judgement. He was very demanding and quite strict when it came to phrasing and rhythmic vitality and he wanted, above all, a complete involvement in the music.”

When Mme. Bachauer’s funds ran out, she returned to Greece to try to make a living as pianist. Her debut in 1935 with the Athens Orchestra under Mitropoulos did not launch her performing career as she had hoped, so she taught at the Athens Conservatory until she had saved up enough money to embark on a concert tour of Europe. However, World War II broke out during her tour, and she was left stranded in Cairo for its duration. Mme. Bachauer became a “kind of pianist-in-ordinary” for the Allied troops in the area, playing roughly 630 recitals in camps and hospitals. One soldier wrote:

“I have just returned to the camp after Madame Gina Bachauer’s concert, so thrilled and so elated that I feel I must write to you at once, although it is near midnight, while I am still under the spell of her music… How right you were to praise Mme. Gina! She is superb! She was like an orchestra.The Concert Hall was full to overflowing with people who applauded her with enormous enthusiasm. Mme. Bachauer had to give three encores to satisfy her acclaiming listeners, another proof of her kindness as she must, by that time, have been very tired.”

While in Egypt, she also married John Christodoulo, who died suddenly in 1950.

After the war, Mme. Bachauer traveled to London where she was introduced to orchestra conductor Alec Sherman, who engaged her as a soloist. The two eventually married, and Sherman gave up part of his career to become her manager, saying there are many conductors, but only one Gina Bachauer.

Mme. Bachauer’s London debut was at the Albert Hall in 1947, and her New York debut was at Carnegie Hall in 1950. She also gave the first solo recital, as Founding Artist, in Washington D.C.’s Kennedy Center. She maintained a demanding concert schedule, playing 110-120 concerts a year on six-month tours alternating between the USA and the rest of the world.

Gina Bachauer traveled to Utah many times and formed a close bond with her audiences and the Utah Symphony, which she performed with under Maurice Abravanel. On one occasion, Mme. Bachauer played with the Symphony accompanied by her pupil, Her Royal Highness Princess Irene of the Hellenes. Mme. Bachauer became a close friend of Maestro Abravanel and spoke very highly of the Utah Symphony. She helped make their first international tour a reality in 1966 when the symphony traveled to Greece, Yugoslavia, Austria, Germany, and England.

Mme. Bachauer’s outstanding capabilities as a concert pianist endeared her to famous New York Times music critic Harold Schonberg, who wrote, “She is one of today’s pianistic originals. That means her technique and her interpretations are sui generis. One does not have to see her to recognize her playing. Ten measures would be enough for any trained listener to put his finger on what constitutes a Gina Bachauer performance. Certain traits are immediately apparent. There is the enormous technical solidity, including a bravura, when necessary, that is hair-raising. She makes piano playing sound very easy. There is the curiously penetrating tone…so well manufactured, weighted, and measured that it sounds enormous.”

After a recital at Carnegie Hall, Schonberg declared, “Governments rise and fall, and the seasons change, but Miss Bachauer’s playing remains a constant. She represents the romantic tradition in piano playing—she, with her enormous technique, her big and penetrating tone, her love for the piano as a steed upon which to ride…Gina Bachauer continues to be one of the great pianists.”

Theodore W. Libbey, Jr., classical music editor of High Fidelity, wrote “Her pianism had the sort of energy and scale and sweep that a listener, once he had experienced it, could never forget. Today, nearly ten years after her death, the memories are still vivid. The mind’s ear still recalls the sound she produced, the brilliant tone, the intensity of her passage work, the weight and clarity of, for instance, the opening chords of the Rachmaninoff Second Concerto. Few pianists of either sex make such an impression when they perform; fewer still make it in a way that lives on after they are gone.”

Mme. Bachauer died in Athens on August 22, 1976. In addition to her pianistic genius, her friends remembered her benevolent personality and lively character. “She has a presence that can irradiate a restaurant,” Martin Mayer wrote, “and a laugh that booms pleasure through the area within earshot. She sits severely erect, a big woman with square shoulders, her dark hair caught back tight in an enormous bun. She makes relatively few gestures when she speaks, and the magic is done by a very mobile expression and incredibly lively, darting eyes.”

In addition to her vivaciousness, she was also very hard working. She often showed up to concerts early to push the piano into place, and completely memorized pieces before attempting them. “Music is an art that is full of beautiful moments [and] extraordinary experiences,” she said, “but it is an art that demands that you give and give. It doesn’t take half measures, you must devote all your life… And certainly…music also needs a little madness. If you aren’t a little mad, you will never undertake this life!”

To preserve the legacy that Mme. Bachauer left behind, her husband bequeathed her personal papers, recordings, photos, and over 200 scores to the Brigham Young University library, which created the Gina Bachauer Archives. Among the scores are the original manuscript copy of Michael Tippett’s oratorio A Child of our Time, and many personal greetings, dedications, and annotations from composers.

Brigham Young University was also the first home of the Gina Bachauer International Piano Competition. In its over 30 years, the Gina Bachauer International Piano Competition has held festivals and competitions every June, bringing the best pianists in the world to Utah to perpetuate the pianistic art which Mme. Bachauer so graciously shared with the world.

https://www.bachauer.com/about/the-life-of-gina-bachauer.html