Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

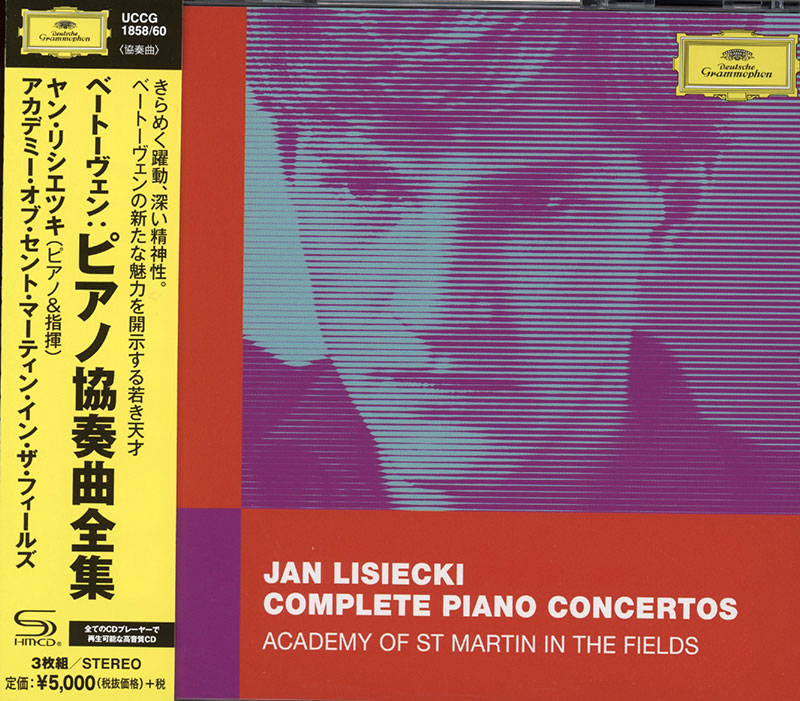

BEETHOVEN, Jan Lisiecki, Academy of St. Marin in the Fields

Complete Piano Concertos

Jan Lisiecki, at the age of 24, already has an impressive discography of recordings of old warhorses by Chopin, Schumann and Mendelssohn (the latter reviewed in these pages). Now he turns his attention to the complete piano concertos by Beethoven, Directing the Academy of Saint Martin in the Fields from the keyboard, thus strays into a difficult territory of pianist/conductor, like Leif Ove Andsnes and Howard Shelley, the conductor of his Chopin Concertos. Beethoven’s first concerto starts with promise in the orchestral tutti, but this is sadly short-lived. Tempo choices across all three movements are brisk, the architecture is not fully realized and dynamics lack subtlety. Continuing in the same vein, all the movements of the Second Concerto exhibit monochrome expression. In the second movement, the piano tone is unduly bright while the Haydnesque wit of the third movement’s Rondo theme becomes repetitively tiresome. Lisiecki’s Beethoven’s Third Concerto has more color and, generally speaking, is more musically convincing. Yet the articulation is not as stylistic as in Paul Lewis or Howard Shelley’s versions, nor does the performance unfold in the same way; it’s all rather matter-of-fact and slightly dry in the first movement. The slow movement is an admirable reading, but lacks the sense of drama in the key changes, followed by a slightly aggressively edged finale. The booklet eludes to the fourth concerto as the one Lisiecki has the greatest affinity with, and his engagement in this Concerto is, indeed, the most apparent, as well as the most impressive synchronization with the orchestra compared with the rest of the concertos. But Lisiecki’s bright tone, even from the opening chords that no two pianists play the same, detracts from the air of mystery, which never fully establishes in this groundbreaking piece. In the fifth concerto (“Emperor”), whilst there is a grandeur in both the orchestral and piano playing, the majesty isn’t fully realized. The slow movement is hastily ensembles, negating its serene calmness, while the excessive speed of the Finale prevents from any sense of buoyancy to sneak in. Lisiecki’s tone is not consistent, especially in the upper register of the piano, which at times is harsh and brittle. This softens considerably (but not intrinsically), in the Fourth and Fifth concertos. Some balance of the hands leans excessively to the right, at the expense of left-hand details, in the first and fifth concertos especially. Unison passages are occasionally labored too, notably in the second concerto. Ornaments, instead of being a small embellishment to the melodies, become overly prominent. Recording all of Beethoven’s five Piano Concertos live is a tour de force. Taken at the Konzerthaus, Berlin in December 2018, the engineering falls short of the expected standards from DG. The recording balance does nothing to enhance Lisiecki, the ASFM or Beethoven’s textures. The small body of strings in the first concerto often sound misplaced, and second violins are frequently too far away. This is also a significant problem in the Fifth Concerto. Woodwinds are occasionally overbearing, with the flute in the First and Second concertos especially piercing. Timpani often sounds distant. Quieter sections are troubled by hissing, while there are distractions from the audience and platform alike, most significantly throughout the third and fifth concertos. The booklet disappointingly lacks both style and substance. The color scheme is striking but jarring. The liner notes, starting with the fourth Concerto, lack flow and sense of cohesion, but do reveal some of Lisiecki’s views on the Concertos. The early concertos especially, with their narrower emotional range, take a highly experienced pianist to seek out the most detailed subtleties. Commendable cycles by Perahia and Uchida bring classical sophistication to their refined performances. Uchida’s slow movements are poetic masterclasses of pacing and expression. Lewis’s darker, more serious approach offers a different perspective. Shelley brings something of himself, as he does to everything he plays, the breadth of his repertoire and experience are indisputable. Andsnes ‘Beethoven Journey’ with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, in which he took time to get to know these works intimately, finds the meaning within. Andsnes understands the Mozart parallels and plays his cycle with a pristine vision throughout. Lisiecki’s performances are full of youthful naivety, but having the ability to play the notes is not sufficient in this repertoire. There is much to be said for mastering one skill at a time; pianist, communicator, director. These three very different attributes don’t unify easily and here they fail to convince. From a musician so admirable this is quite disappointing.

Płyty SHM-CD do odtworzenia we wszystkich typach czytników CD oraz DVD. Gwarantują niespotykaną wcześniej analogową jakość brzmienia, odwzorowują wszystkie walory taśmy-matki. Zdaniem specjalistów - ten nośnik i ta technologia najlepiej - bo natywnie, przenosi na krążek CD wszystkie walory nagrania analogowego. |