Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

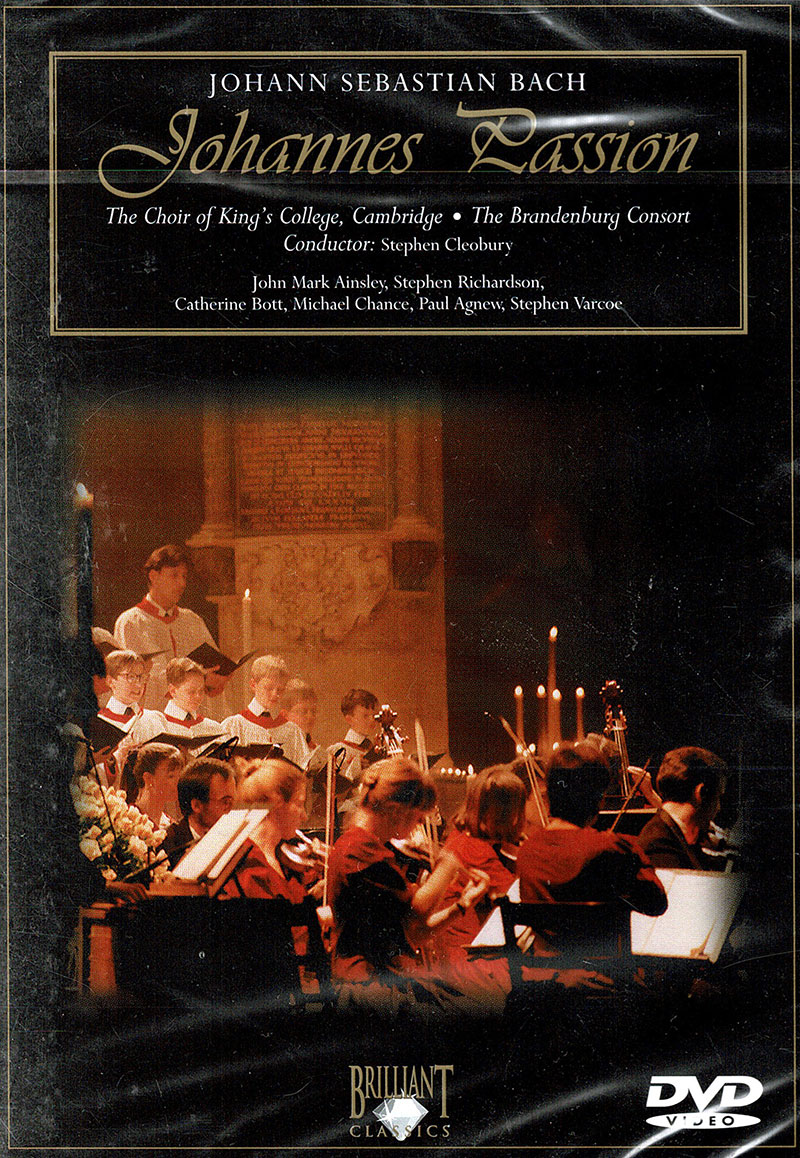

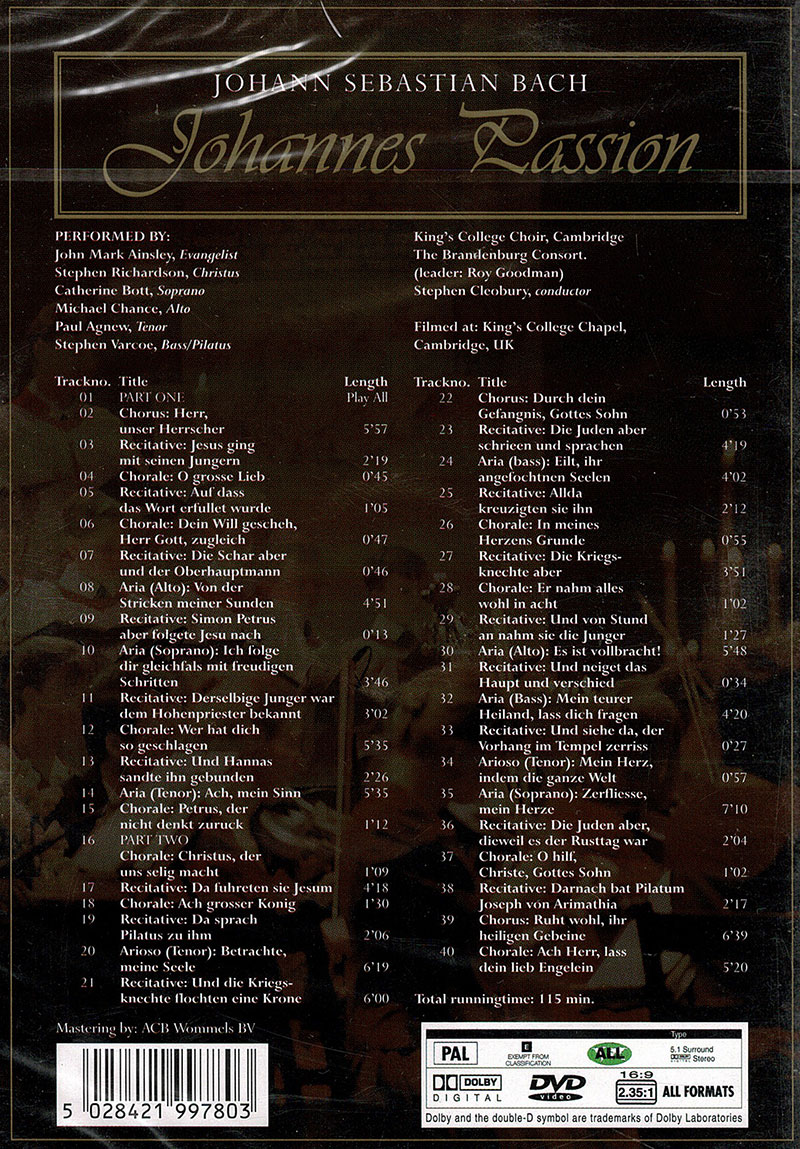

BACH, Choir of King's College, John Mark Ainsley, Brandenburg Consort, Stephen Cleobury

Johannes Passion

Both performances have been reissued several times, mostly by Brilliant Classics, but on other labels as well. The CD set gives no other information, save for the year of the original copyright, 1995. The case also is unclear about what version is being performed. In fact it’s a recording of the more oft-encountered recorded 1724 version, which was premiered in the St. Nicholas Church in Leipzig on Good Friday, 7 April 1724. The DVD, on the other hand, presents the version premiered one year later in the St. Thomas Church, Good Friday, 1725. Moreover, the CD includes an Appendix with the five movements that changed between the 1724 and 1725 versions. So, with a little programming, you can listen to an audio recording of either version. The excellent notes, by Bach scholar Malcolm Boyd, address the two versions, but the libretto is printed in German, without any translations. Nevertheless, Brilliant Classics have created a very capable package with this issue. It is fascinating to compare the two versions, as well as - what I presume to be - two differing performances by the same forces. Boyd writes in the liner-notes that the 1725 version was meant to “shift the emphasis of the work from an assertion of Christ’s majesty through his crucifixion to a recognition of human sin and repentance perhaps more in keeping with orthodox Lutheranism.” That is clear right from the opening: “Herr, unser Herrscher” (1724 version) is a massive da capo polyphonic chorus, the text proclaiming “Lord, you are our master”. The 1725 version begins with a simpler, more subdued setting of the text “O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß” (O mankind, mourn your great sins). This chorus was later transposed and used at the end of the first part of the St. Matthew Passion. Both readings feature truly wonderful playing from The Brandenburg Consort. Tuning is immaculate, and on the DVD we see how much eye contact and listening goes on amongst the players, resulting in playing that is both exacting and passionate in equal measure. The many instrumental solos are, without fail, beautifully realized. Special mention must be made of the cello soloist for her work in the unfamiliar Bass aria, “Himmel reisse, Welt erbebe” (Heavens tear apart, the world quakes) from the 1725 version. The writing for both the cello and tenor is fiercely angular and disjunct, fully capturing the text’s imagery, and thrilling realized by the unnamed cellist and Paul Agnew. It is a shame not to have the names of the players listed, as their obbligato passages add immeasurably to the soloists’ music. John Mark Ainsley’s Evangelist is a vivid storyteller, ever aware of the need not only to tell the story but also to convey the meaning of the story. His moments of high drama, particularly Peter’s weeping after his denial of Jesus and the scourging of Christ, have overwhelming impact. Stephen Richardson’s Christus is affecting, more so on CD then DVD. The DVD audio somehow distorts Richardson’s dark vocal timbre, making it sound muffled. Catherine Bott’s soprano sometimes develops a steely edge, though it sometimes is perfectly suited to the text she is singing. Michael Chance is in fine form, the added warmth of King’s College Chapel acoustic making his “Es ist vollbracht” more poignant than his earlier recording with Gardiner and the English Baroque Soloists on Archiv/DG. Stephen Varcoe contributes wonderful singing, and makes the most of his role as Pilate, allowing us to see a ruler struggling to grasp the difficult position in which he finds himself. The singing of the Choir of King’s College Cambridge proves to be a conundrum. In both performances their singing is accomplished, with excellent intonation and diction. Yet the tragedy of the story is only intermittingly caught in the DVD. Too often the singing seems disconnected. Yet on the CD it is more consistently intense; is it possible that the DVD was made first when the choir had only rehearsals of the work under their belt? Whatever the reason, the choir’s performance is markedly superior on CD. The DVD production is basic - there are no extras and no subtitles. Ainsley was apparently asked by the director always to look into the camera while singing. Perhaps this is meant to draw the home viewer into the story, but I found it disconcerting and distracting. Cleobury is clear and efficient, though hardly inspirational to watch. I derived a great deal of enjoyment watching some of the more unusual instruments in performance (the viola da gamba in “Es ist vollbracht” and the oboe da caccia in “Zerfliesse, mein Herze). Despite the excellence of these performances, neither would be a prime recommendation. For a DVD version, I would seek out the one by the Bach Collegium Japan, conducted by Masaaki Suzuki on Euroarts. On CD I would go for John Eliot Gardiner most especially the later one on his SDG label. Made after the famous Bach Pilgrimage, the performance, warts and all, is filled with a special insight that comes from spending so much time with the music of Bach. John Mark Ainsley (tenor) - Evangelist; Stephen Richardson (bass) - Christus; Catherine Bott (soprano); Michael Chance (alto); Paul Agnew (tenor); Stephen Varcoe (bass) - Pilate King’s College Choir Cambridge The Brandenburg Consort/Stephen Cleobury