Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

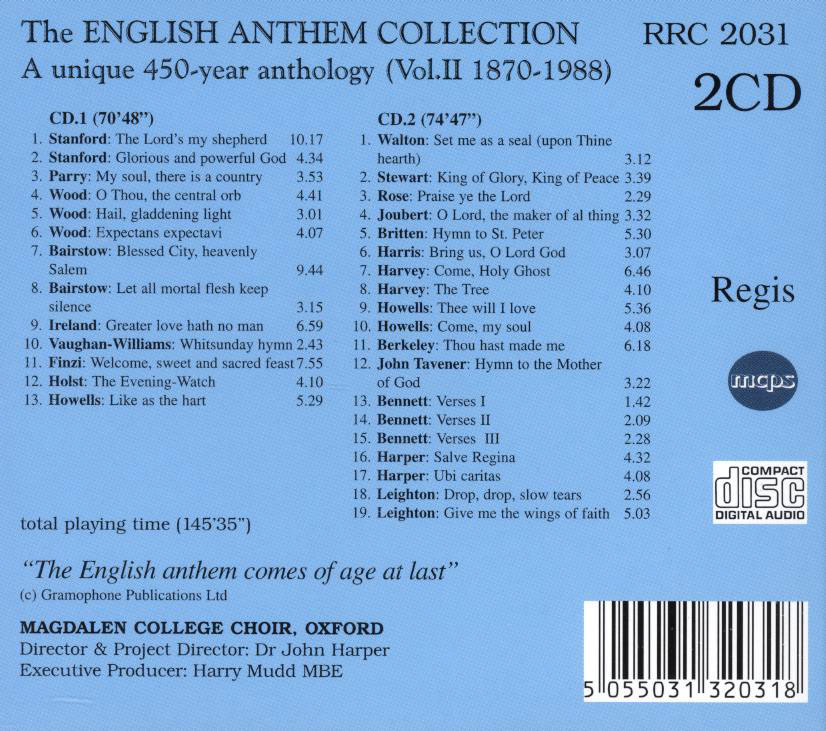

STANFORD, PARRY, FINZI, BRITTEN, VAUGHAN-WILLIAMS, Choir of Magdalen College Oxford

Anthology of English Anthems 1871- 1990

- 1. Stanford: The Lord's my shepherd 10.17

- 2. Stanford: Glorious and powerful God 4.34

- 3. Parry: My soul, there is a country 3.53

- 4. Wood: O Thou, the central orb 4.41

- 5. Wood: Hail, gladdening light 3.01

- 6. Wood: Expectans expectavi 4.07

- 7. Bairstow: Blessed City, heavenly Salem 9.44

- 8. Bairstow: Let all mortal flesh keep silence 3.15

- 9. Ireland: Greater love hath no man 6.59

- 10. Vaughan-Williams: Whitsunday hymn 2.43

- 11. Finzi: Welcome, sweet and sacred feast 7.55

- 12. Holst: The Evening-Watch 4.10

- 13. Howells: Like as the hart 5.29

- CD.2 (74'479')

- 1. Walton: Set me as a seal (upon Thine hearth) 3.12

- 2. Stewart: King of Glory, King of Peace 3.39

- 3. Rose: Praise ye the Lord 2.29

- 4. Joubert: O Lord, the maker of al thing 3.32

- 5. Britten: Hymn to St. Peter 5.30

- 6. Harris: Bring us, O Lord God 3.07

- 7. Harvey: Come, Holy Ghost 6.46

- Choir of Magdalen College Oxford - choir

- STANFORD

- PARRY

- FINZI

- BRITTEN

- VAUGHAN-WILLIAMS

Much scorn has been poured on nineteenth century English music, and on English church music above all. Its sentimentality and its spinelessness, its dependence on foreign models and its lack of taste have been ready targets. But whatever the perceived flaws of most of the repertory of nineteenth century church music there are striking moments in many of the best works; and in its attention to formal planning, compositional craft and careful declamation of text this repertory identifies readily with a Church that was building on solid and optimistic foundations, the product of composers with a strong pedagogic element in their careers. Cutting across the divisions of style, idiom, resource and aesthetic is the choice of texts. There are three categories: translated hymns, seventeenth century texts (prose and verse), and biblical texts. Of the hymns translated from Latin, Bairstow set nineteenth century translations, but Vaughan Williams Whitsunday Hymn is one of a group of Coverdale settings, and Joubert set a sixteenth century version of the Compline hymn Te lucis. The number of seventeenth century texts reflects the attention accorded to this period of English literature at this time (1900-1960). Both Finzi and Holst set poems by Henry Vaughan, Stewart chose George Herbert and Harris the prose prayer by John Donne. Of the biblical texts, Walton used the Song of Songs (a ready source for a wedding anthem), Ireland turned to St John, and Britten drew on the antiphon for St Peter's day (a compilation of texts). Both Howells and Rose turned to the Psalms (Howells to Psalm 42, Rose to Psahn 149 but in the Authorized Version). The unaccompanied partsong was widely cultivated in Victorian England, and it forms the starting point for the unaccompanied anthems by Parry and Stanford. Charles Wood's Hail gladdening light is scored for two four-part choirs, and depends on spatial antiphony. Wood's accompanied anthems are both conceived on a relatively contained scale. Both display the assured craft of a composer working in the period after Brahms. Stanford's The Lord is my shepherd is a larger work written some thirty years earlier (1886). It too bears the influence of the Viennese symphonic tradition. The twentieth century was a period of rapid musical change, and - for all its conservatism - English music reflected that change. Though there was nothing avant-garde to be found in the repertory pre-1960 of this anthology, there are important signs of modernism. Alongside this is the tradition and craft of choral writing most easily identified in the unaccompanied works of the organistcomposers - Bairstow, Stewart, Harris and Rose. There is not space here to discuss the music itself in detail, but it seems important to single out one composer for comment. Set against the international stature of Vaughan Williams, Holst and Britten, it is easy to underestimate the modernism of Howells. Because he has written so much for the church it has been easy to pass over his contribution to the exploration of musical expression in England. Howell's understanding and treatment of voices, organ, modal melody and harmony, and acoustic are widely influential and original. As a collection, the early twentieth century anthems seem distant from the liturgy (all the music stands up regardless of a liturgical context), let alone from the turmoil that affected the church (from the failure of the 1929 Prayer Book to the human devastation of two World Wars). That detachment seems to be a reflection of the age as a whole rather than of the music. But beneath this surface appearance there is a discernable and deep humanity, and human spirituality. In a number of instances the spirit seems religious rather than specifically Christian, and that too reflects the age and some of the composers. The background of chant and, more generally, of modal melody, is important in a number of works included here. The improvement in choral singing in the twentieth century and the desire to be free of the organ are also apparent: a large proportion of these pieces are unaccompanied. A wistful lyricism is present in a number of the works, notably those by Ireland, Vaughan Williams, Finzi, Holst, Howells and even Walton. More robust are those by Bairstow, Stewart, Joubert, Rose, Britten and (in a restrained context) Harris. To see post-war works by Joubert and Britten in this second category may be no surprise, but it is significant that this more positive aesthetic is adopted by the organist-composers. The last thirteen pieces in this anthology of the English Anthem were all composed post 1960. It seems important that music of our own time and generation should be represented in its own right. Historically this is also an important time: within the church there have been far-reaching changes in the forms and styles of worship, and several new departures are evident in music written for the church. Placed in a wider context, the trends in composition in the English-speaking denominations seem to be encouraging, even though the choral institutions themselves are subject to constant scrutiny and questioning relating to their function and worth. Throughout Europe the zenith of church patronage passed in the seventeenth century. Since that time the composers have (in general) devoted less of their time to liturgical composition. In England the Commonwealth (1649-1660) effectively broke the continuity of liturgical music with the disbanding of choral foundation and the suppression of much music in worship. The flourish of activity that followed the Restoration of the monarchy (1660) was largely confined to Royal foundations in London. In England and throughout Europe the general preference has been for a conservative idiom in church music, often deterring those composers who were or are active Christians from writing for the liturgy. This has been particularly the case in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with one striking exception: Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) was a composer who had been at the forefront of modernism, and in all his music Christian theology and mysticism were ever-present forces. There has, of course, been other religious music that has prospered in the Christian church (notably hymnody in the broadest sense). But, in general, each wave of liturgical reform has challenged and weakened the place of music in worship since the sixteenth century. And the period since 1960 has been one of the most turbulent times of liturgical reform since the Reformation, with revisions of rites and language as well as of theological and pastoral emphasis. In carrying out these revisions, the displacement of `art music' for trained musicians and singers has been widespread: in some Christian denominations texts and music used for centuries has become redundant almost at a stroke. Much that has replaced the `old' music has pastoral vigour but often lacks intrinsic worth: it draws frequently on secular idioms but often in a watered-down, derivative manner. The same criticism may be levelled at some of the traditional church music of the past century or more, but in recent years there have been more optimistic signs. Part of the challenge of liturgical reform has been that established choirs and musicians have questioned and revalued their work and role. Though there are fewer well-established church choirs, even in England, many are technically more competent than in the past. Some clergy have been enlightened in fostering the contemporary arts in the church, including music; and some composers have responded. Jonathan Harvey is a contemporary English composer of international standing, well acquainted with avant-garde techniques of composition. He is also a Christian with strong commitment to the place of music and the arts in the spirituality of the church. During the 1970s he formed an association with Winchester Cathedral (especially with the then Bishop, Dean and Organist) which led to a series of commissions. Winchester Cathedral Choir, at the same time, increased its technical capacity to sing advanced music. Some of the fruits of all this may be heard in two works written for Winchester - Come, Holy Ghost and The Tree. Come, Holy Ghost (1984) is a series of variations on the Pentecost hymn, and demonstrates important features of Harvey's style. Its use of a plainsong hymn melody provides modal stability (with no compromise in the harmonic language); it is written from the middle of the texture outwards; and it employs aleatoricism in the last main section. It is a taxing work with up to sixteen independent vocal lines, and yet it is both lyrical and spiritual. By contrast, The Tree (1981) is scored for boys' voices and organ: only in the last phrases does the vocal line divide. Here again there is lyricism, but within the framework of a 12-note chromatic pitch series. The Winchester connection also led to John Tavener's Hymn to the Mother of God (1987). Since he moved from the Roman Catholic to the Orthodox Church, Tavener's music has been affected strongly in both aesthetic and idiom by the Byzantine tradition. This short hymn demonstrates these features. The static quality of the piece gives a sense of timelessness, and of profound, but intimate spirituality. The idiom of harmonized choral chanting is taken over from the Orthodox Church, and Tavener achieves the specific effect in this piece by superimposing the same music sung by each of the two choirs in canon. A Winchester association persists in Harper's Salve regina. This was written to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the death of the founder of Magdelen College, Oxford (William Waynflete, Bishop of Winchester and Chancellor of England) and was sung by Magdelen College Choir at his chantry in Winchester Cathedral in July 1986. It is the only work in this modern group with a text entirely in Latin, and makes use of the plainsong melody and tropes found in the medieval Use of Salisbury. It is included as a reminder that the original anthem (or antiphon) was a feature of the pre-Reformation Latin Rite, a song sung in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary, most often at the end of Vespers or Compline. Its popularity in England led to numerous polyphonic choral settings in the fifteenth and earlier sixteenth centuries. And of all the texts sung, Salve regina was the most common and well loved. Ubi caritas (1988) was also written for Magdelen College Choir. It is a macaronic setting: the refrain of the plainsong is sung in Latin, but the verses are sung (and spoken) in English. The whole work is a decoration of a chord of F sharp major. These two works are a reminder that much of the choral repertory of the church throughout the ages has been composed by organists and choral directors for the resources available to them, and for the liturgy of the ecclesiastical institutions they serve. Much has gone by the wayside, but the best circulates and survives. The remaining music is by established composers, and reflects an idiom that was especially characteristic of the 1960s. By comparison with the underlying lyricism and consonance and the overlaying of voices and textures evident in the works discussed so far, the other works tend to emphasize clarity of line, have more forward drive, and a grittiness that even tends towards the aggressive. In some ways these features echo the brutalism of some progressive architecture of the period. Lennox Berkeley's setting of John Donne's sonnet Thou hast made me was written in 1960. Though Berkeley had a preference for Latin sacred texts and made no secret of his regret at the passing of the old Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church, he composed a number of English anthems of which this is one of the best. The driving, scherzo-like middle section is flanked by more wistful writing, so characteristic of Berkeley, with powerful moments of climax. Kenneth Leighton wrote a great deal of church music for both English and American choirs, some of it deliberately functional (like the Communion Service in D), some very demanding. The moving, unaccompanied setting of Drop, drop slow tears comes from the choral cantata Crucifixus pro nobis (1961). Give me the wings of faith (1962) is one of his most widely sung anthems. It demonstates his use if strong vocal lines (often paired), his organ writing, and the bold harmonic language with the frequent use of chords based on fourths. Richard Rodney Bennett is an eclectic composer and performer. The three settings of verses by Donne are comparatively early works (1965), but demonstrate the best of his highly disciplined style, here austere and yet compelling, well suited to the serious mood, and sensitive to the high literary quality of the texts. The importance of Howells' restrained and individual modernism is argued above. In his later years his style changed a good deal, becoming more angular and forceful. Though he lost none of the sense of line or mood, the expression seems less languid, more astingent. The driving metre of Thee will I love (1970) is especially striking - far removed from the reflective mood of Like as the hart. And Come my soul (1978) is a significant example of his late writing for unaccompanied voices; and a telling text to be set by a man in his eighties. © original notes by John Harper, edited for new collection by James Murray