Logowanie

ABSOLUTNIE OSTATNIE!!!!!

SpeakersCorner - OSTATNIE!!!!

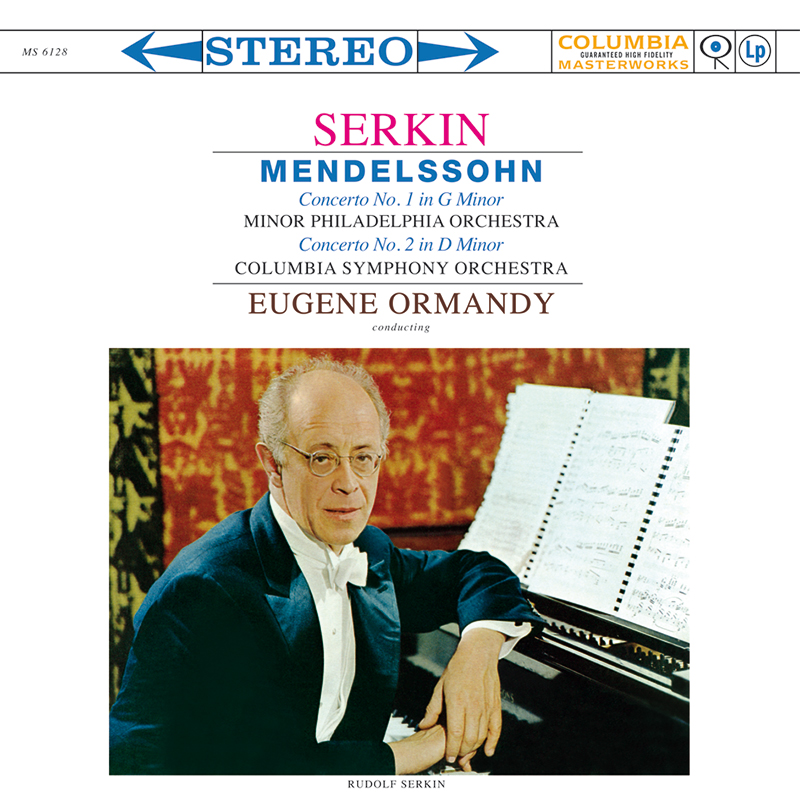

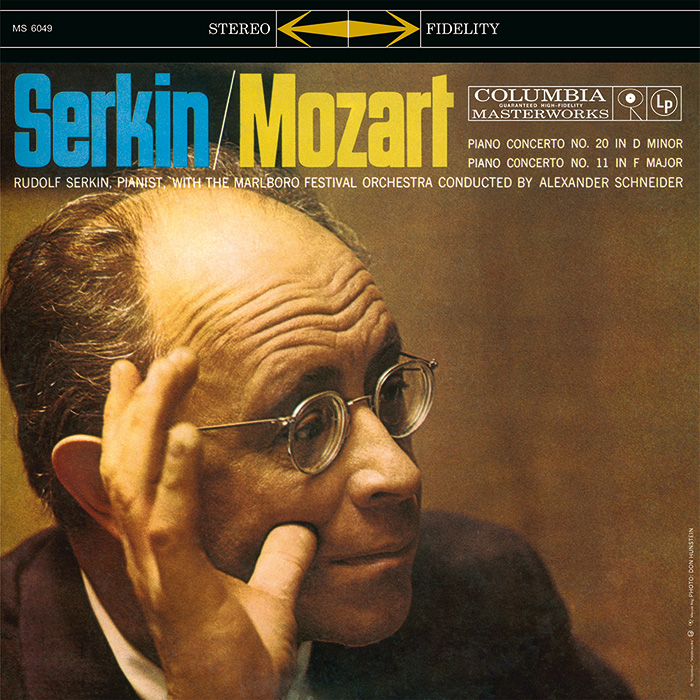

MOZART, Rudolf Serkin, Alexander Schneider, Marlboro Festival Orchestra

Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor / Piano Concerto No. 11 in F Major

Columbia Masterworks

Wzorcowe

Carmen Gomes

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 5 - Reference Songs

- CHCECIE TO WIERZCIE, CHCECIE - NIE WIERZCIE, ALE TO NIE JEST ZŁUDZENIE!!!

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Gregor Hamilton

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 2 - Love songs from Gregor Hamilton

...jak opanować serca bicie?...

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 1 - Leonardo Amuedo

Największy romans sopranu z głębokim basem... wiosennym

Lils Mackintosh

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 4 - A Tribute to Billie Holiday

Uczennica godna swej Mistrzyni

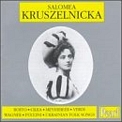

PADEREWSKI, VERDI, Salomea Kruszelnicka

Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 1. The Piper's Song op. 18 Nr. 2

- Komponist Ignaz Paderewski

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 2. Halka: I Wish I Were A Lark

- Komponist Moniuszko

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 3. Peer Gynt op. 23: Solveigs Lied

- Komponist Edvard Grieg

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 4. Tosca: Vissi d'arte (Nur der Schönheit weiht ich mein Leben)

- Komponist Puccini

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 5. Mefistofele: L'altra notte in fondo al mare (Dort im Wald in trüben Lachen)

- Komponist Boito

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 6. Adriana Lecouvreur: Ecco...lo son l' umile ancella (Sehen Sie...Ich bin nur die Magd)

- Komponist Cilea

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 7. Die Macht des Schicksals: Pace, pace (Frieden, Frieden)

- Komponist Verdi

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 8. La Wally: Ebben, me ne andro lontan (Nun denn, so laß mich ziehen)

- Komponist Catalani

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 9. Aida: Ritorna vincitor (Als Sieger kehre heim)

- Komponist Verdi

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 10. Adriana Lecouvreur: Poveri fiori (Ihr armen Blumen)

- Komponist Cilea

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 11. Loreley: Allor, che tutta noi...

- Komponist Catalani

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 12. Die Walküre: Hojotoho, hojotoho

- Komponist Wagner

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 13. Die Walküre: Tanto fu triste

- Komponist Wagner

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 14. Madame Butterfly: Un bel di vedremo (Eines Tages sehn wir)

- Komponist Puccini

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 15. Die Afrikanerin: Von hier seh' ich das Meer

- Komponist Meyerbeer

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 16. Wiwcy moi wiwcy

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 17. Zcerez sad wynohrad

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 18. Oi, de ty idesz

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- 19. Oi, letily bili husyn

- mit Salomea Kruszelnicka

- Salomea Kruszelnicka - soprano

- PADEREWSKI

- VERDI

The first thing to agree on about this singer is her name. For present purposes she is Salomea Kruscelnicka, but in Italy, where she made her career, she was Krusceniski and it is in that form that she is entered in most encylopaedias (including The New Grove Dictionary of Opera) and most indexes (such as that of Michael Scott's The Record of Singing). Occasionally she turns up as Kruscelnickaya, and a Kh to start with is not unknown. Her place in history (see The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera under Krushelnytska) is as Italy's first Elektra and as CioCio-San in the first successful performance of Madama Butterfly, withdrawn after the fiasco of its first night at La Scala, Milan, revised and reintroduced at Brescia later in 1904. Her place on the record collector's shelves is a doubly honoured one, her records being as good as they are rare. She was one of those pre-electrical sopranos who do not sound pre-electrical (Celestina Boninsegna, q.v. GEMM CD 9980 and 9219, being the most obvious of her counterparts in this). She is also a singer for whom modern listeners, with modern expectations, do not have to make too many major adjustments: she sings, for the most part, with attention to the details of the score and takes care to make verbal, as well as musical, sense with her phrasing. These last points, it must be admitted, cannot be said to apply to the record of Solveig's Song and the `Vissi d'arte' made in 1902. In the Grieg she is slack on the dotted-note figure of the verses' second half, and in the Puccini she hurries from "Sempre con fe sincera" onwards but still takes a breath and so breaks the phrase in "Diedi fiori agli altar". She was at that time a leading soprano in Warsaw and an artist with international experience. A great difference is notable, however, in her next set of recordings, made at Milan in 1906. By then she was well established in Italy and South America, had no doubt learnt much from singing under Toscanini, and was all set for what were to be the great years of her career, opening on the Christmas Eve of that year with her debut at La Scala. The recordings show her fully ready for it. The four operatic arias recorded in those November sessions represent a great singer in her prime. The voice has a distinctive mezzo-soprano colouring, yet the high notes are of fine quality too, especially in the `Pace, pace, mio Dio' from La forza del destino. The technical fluency of her arpeggios and cadenza in Margherita's prison aria from Mefistofele is masterly, and her trills (often shirked by Italians in this aria) are well spun. This is also a voice of considerable power, and the conditions of recording, which inhibited many sopranos in those days and prevent the listener from gauging the effect such a voice would have in the opera house, seem not to affect her. The fullness of her tone in the upper-middle register is particularly satisfying in her Adriana Lecouvreur aria. At the start of that she impresses as a natural recording artist, ready to move (after the tragic darkness of the Mefistofele) in voice-character from one role to another. Occasionally an unevenness of vibrato obtrudes, as on the climactic note of the aria from La Wally and, also occasionally, there is a very slight flattening (some examples in the Mefistofele). But her performances are the real thing: they are events, times of deep feeling and intense concentration. She has a lovely sense of when and when not, how much and in what manner, to use portamento, the `curve' from one note to the next, so little understood by singers nowadays and so vital for singing as an exercise in expressive humanity. In this respect the Wally aria is supreme: a most hauntingly tender, convinced performance, with every stylistic feature serving an artistically emotional end. When the orchestra (no mistaking the pre-electrical sound there) comes in to supplant the pianist in 1907, we find the singer recorded slightly less to her advantage. By way of compensation, Aida's 'Ritorna vincitor' is granted what was then the luxury of two sides (or two discs). Accordingly, there is no rush, and the full range of feeling in this solo can be explored. In the second of the arias from Adriana Lecouvreur we have possibly the most perfect of Kruscelnicka's recordings, with a very feminine softening of the tone, a restrained mood of brooding fatality, and in the final °e fmita" an emotional fulfilment uncheapened by the melodramatic manners that were all too common among the singers of such `verismo' operas. The gap of five years between those and her 1912 recordings is of course lamentable, but only one of many such sad lacunae in the history of recording. In between had come the Elektra premiere, a succes d estime rather than anything else with the Milanese, and not heard again in the house till 1932. The 1912 recording sessions have nothing of that in them, though they do bring to notice another of Kruscelnicka's activities, namely the prominent part she played during those years in introduc ing and confirming the later Wagner as an acceptable composer with audiences in both Italy and South America. The samples we have of her Walkure Brunnhilde suggest what we may well have suspected, that hers was a lyric-dramatic but not an heroic soprano. T Tie steel and amplitude of tone, the sturdy fullness of lower notes, are suitable for an Aida, a Sieglinde maybe, but not quite for Brunnhilde. Nevertheless, these are performances that win respect - nothing is fudged in the Battle Cry, and the plea has genuine warmth. The aria from Catalani's Loreley (one of the last roles she sang before retiring from opera in 1920) suits her better, as does 'Un bel di', the sole memento of her part in the great revival of Butterfly's fortunes at Brescia. Most remarkable, however, is the hallucinatory solo of Selika in the last scene of Meyerbeer's LAfrlcaine. This has some brilliant florid passages, again hard to think of as sharing a recording session with Wagner. It shows clearly enough the capacities of this exceptionally varied singer and makes all the more regrettable the fact that, with it, Kruscelnicka ended her career as an opera singer on records. She did not entirely terminate her association with the record industry, however. Her reappearance on the fists of American Columbia in 1928 is one of the oddities in `the record of singing', comparable (or almost) to that of the legendary MeiFigner at roughly the same time in Russia. Kruscelnicka was then aged fifty-five: `only' fifty-five, we might say, but it seemed older in those days. She had started a new life as a concert singer, making tours of Italy and other parts of Europe, South America (where she had a longestablished reputation) and now the United States, where she was singing for the first time. She drew on a wide international repertoire, and one of her specialities was a selection of popular Ukrainian songs for which she would play the piano accompaniments herself. These must have attracted the attention of the recording company in Chicago, mindful, perhaps, of the ethnic groups in the city and elsewhere. Eight titles were recorded, all extremely rare in their original form and with words that have defied efforts at translation. The four included here (all with accompaniment by an instrumental ensemble) show the voice in good repair though hardly tested in range; more impressive, perhaps, is the spirit, the gaiety and, in the more serious mood of the third song, something remaining of the great opera singer of the past. Kruscelnicka died in 1952 at Lemberg (or Lwow) in Poland, where she taught at the Conservatory and where, eighty years earlier, she had been born. The acorn, they say, does not fall far from the oak; but this acorn had travelled far and wide before returning to homeground. Something of an infant prodigy, she had been sent away for study in Italy as a young girl. She had been a fully professional singer while still in her teens, and in her twenties had sung in opera houses from St. Petersburg to Chile. She had become a favourite singer of Toscanini, had been chosen for the world premiere of operas by Cilea (Gloria) and Pizzetti (Fedra), and had undertaken some of the most challenging roles in the operatic repertoire (Isolde, Brunnhilde, Salome, Elektra) introducing them to audiences in countries where the general preferences of the public lay elsewhere. It was an honourable career and an adventurous life, commemorated in all too limited a way by the recordings which still testify to a rare distinction of voice and artistry. J.B. STEANE Producer's Note: This superbly voiced and versatile soprano is, alas, another of those irritating artists who took no account of the limitations of the CD medium (cf. Graziella Pareto - GEMM CD 9117). As I wrote then "too much for one, not enough for two." Kruszelnicka is worse, however, in that she duplicated no less than six titles in her limited output, some of them salon trifles (although delightful) by such as Tosti and Quaranta - not to mention Grieg's (boring?) Solveig's Song. As far as playing speeds are concerned, I was interested to note that her G & T records were recorded at the same speed as her first Fonotipias (76 rpm) - a pure coincidence, of course. The speed of her 1928 Columbias is more conjectural, the music being (to me) totally unknown. I have pitched them in believable keys, bearing in mind the relatively advanced age of the singer. Thanks are due to John Paul Getty, Denys Harry and Bill Shaman for the loan of rare records, and to W.R. Moran for his help and information. KEITH HARDWICK