Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

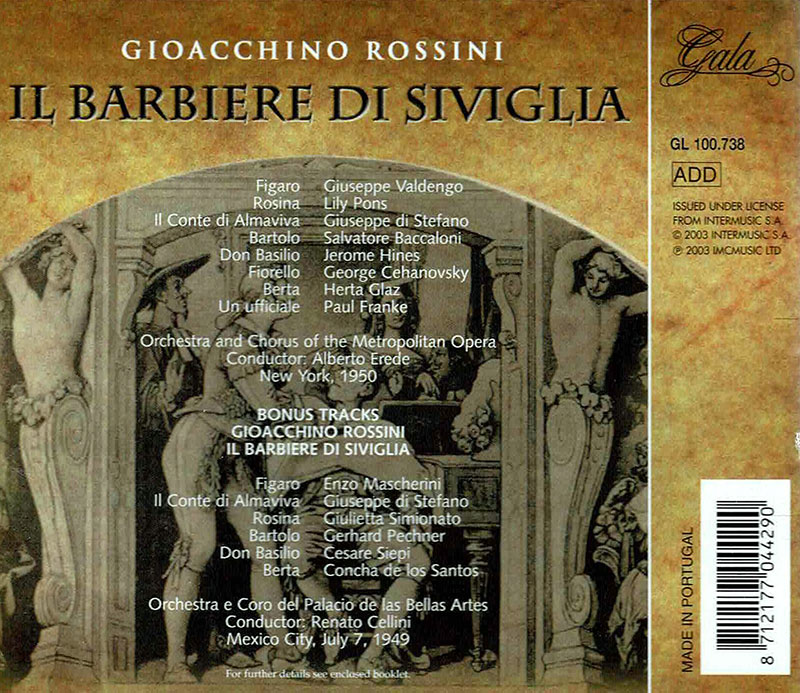

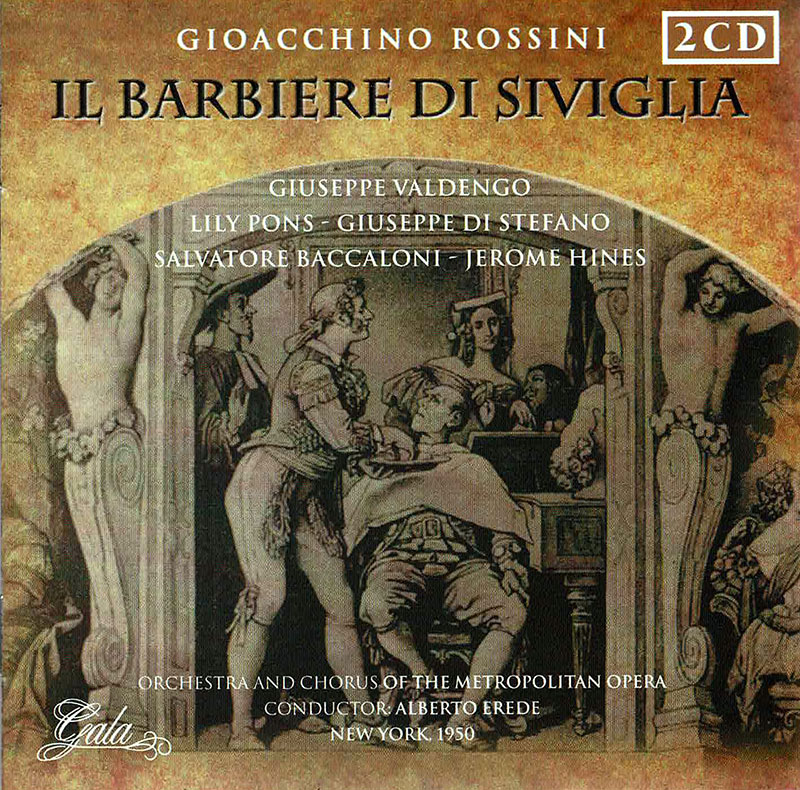

ROSSINI, Giuseppe Valdengo, Lily Pons, Giuseppe di Stefano, The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus, Alberto Erede

Il Barbiere Di Siviglia

this live recording of the December 16, 1950 radio broadcast is newly remastered from the original sources. Soprano Lily Pons sings the role of Rosina, with the young tenor Giuseppe di Stefano as Count Almaviva and baritone Giuseppe Valdengo as Figaro. Alberto Erede conducts the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus, with a cast that includes Salvatore Baccaloni (Don Bartolo) and Jerome Hines (Don Basilio). **** ROSSINI Il barbiere di Siviglia • Alberto Erede, cond; Giuseppe Valdengo ( Figaro ); Lily Pons ( Rosina ); Giuseppe di Stefano ( Almaviva ); Salvatore Baccaloni ( Dr. Bartolo ); Jerome Hines ( Don Basilio ); et al.; Metropolitan Op O & Ch • During the early 1940s, Sir Thomas Beecham. who was scheduled to conduct a performance at the Met, hailed a taxi and told the driver to take him there. The cabby explained that, because of World War II regulations, he could not take Sir Thomas to “a place of entertainment.” “My boy,” said the conductor, “I assure you … the Metropolitan Opera is not a place of entertainment.” I don’t know whether Sir Thomas got his lift or not, but I think he was wrong. Listen to the applause and laughter at the 1950 Barber of Seville listed above and it’s pretty difficult to say that the audience was not having a good time listening to the singing and (especially) observing the onstage antics of the cast (too bad it’s not a DVD). But it’s time for another quote: Observing the celebrated charge of the Light Brigade as it was shot to pieces by Russian guns, an appalled French military observer exclaimed, “It is magnificent, but it is not war!” A drawing-room comedy starring, say, the Three Stooges might, in its perverse way, be “magnificent,” but it would not be a drawing-room comedy. For at least 20 years, I have believed that it has become easier to cast a Barber of Seville, or something of that ilk, than it is to cast an Aida , or something of its ilk. Thinking it might be unfair to compare this Barber with more recent versions, I auditioned several from the 1950s, 60s, 70s, and one from 1983. Then, assuming it would prove my point, I listened to the 1992 Naxos recording, with Will Humburg leading a cast of (to me) mostly unknowns. It did. It’s easily superior in singing and staging to any of the others I auditioned. As for the earlier ones, I may occasionally make references to the recordings led by Erede/Decca, Marriner/Decca (formerly Philips), Galliera/EMI, Leinsdorf/RCA, Abbado/DGG, Gui/EMI, Varviso/Decca, and Levine/EMI. First of all, let me point out that Giuseppe di Stefano, Lily Pons, and Salvatore Baccaloni did not become famous because they were boring singers. Di Stefano, even in the long downward phase of his career, could nearly get by on charisma and charm—he was an imaginative, impassioned performer. Pons, the epitome of operatic glamour during her prime, even had a little town in Maryland (and the road that leads to it) named after her, and Baccaloni’s flair for comedy eventually got him into the movies ( Full of Life, Merry Andrew, Fanny, The Pigeon That Took Rome , etc.) after his opera days were over. For that matter, this performance’s Basilio, Jerome Hines, had a l-o-n-g, useful career as a star bass at the Met, and Giuseppe Valdengo, if not one of the stars of the day, was good enough to sing leading roles on a couple of Toscanini’s recordings. I am pointing out these things because, really, this performance, however “entertaining” it may have been, is merely an approximation of The Barber of Seville. Casting a coloratura soprano as Rosina, instead of a mezzo-soprano, is the least of its sins. Pons, like most sopranos (but not Maria Callas or Victoria de los Angeles on the otherwise flawed Galliera and Gui recordings) transposes “Una voce poco fa” up a half-tone and adheres to the old tradition of interpolating something other than Rossini’s music into the lesson scene (in this case, what sounds like elaborate variations on Adam’s Variations on “Ah, vous dirais-je Maman”). If she doesn’t ornament her part as much as, say, Roberta Peters (Leinsdorf) or Beverly Sills (Levine), she certainly takes her share of liberties. She can still squeeze out a high F but not without obvious effort. Di Stefano had sung the part of Almaviva elsewhere prior to his Met appearance. I assume it was soon dropped from his repertoire. I don’t know how much influence Alberto Erede had over him but I can’t believe all the arbitrary use of rubato and fluctuating tempos (i.e., slowing down to tackle some difficult passages) was the conductor’s idea. In 1950, the tenor’s voice was in good shape and, to give the devil his due, there are times when he caresses his music with such lovely tone that one is temporarily seduced, but, like everyone but Pons, he just can’t handle the rapid passages and most of the ornamentation, sometimes even when he slows down. Bartolo’s showpiece, “A un dottor della mia sorte,” is mercifully shortened, for Baccaloni by 1950 has to fake his way through the fast stuff. He does manage to spit out the rapid-fire words more clearly than most of the recorded competition, which says little for the other Bartolos. Hines and Baccaloni were probably an amusing Mutt-and-Jeff pair to look at. Hines, in young, booming voice, is a crude Basilio with little flair for comedy or even characterization. “La calunia,” too, is shortened, as are a lot of the recitatives. Valdengo is a light, not-too-clownish Figaro, actually the soberest singer in this dizzy cast, but he can’t handle the coloratura, either. Although the performance is on the sloppy, slapsticky side, maybe Erede deserves some credit for even managing to usually stay in touch with the singers. In a way, it’s a virtuoso piece of conducting, but not much else. Of the recordings I listened to, in addition to the excellent Humburg, the only uncut ones were those of Leinsdorf and Levine, but they, too, have some vocal problems. If you must have a performance with singers of the 1960s and 70s, I’d say get Marriner’s or, perhaps, Abbado’s, which have strong virtues to go along with their defects. As for this 1950 performance, in its sloppy, eccentric way, I suppose it’s some kind of magnificent, but it is not Il barbiere di Seviglia. On the other hand, in the 1950s and 60s, casting a Tosca wasn’t much of a problem and the Met had its choice of several more-than-adequate singers who could be put in the leading roles; in fact, I think this 1962 broadcast is competitive with the better studio recordings. Price, in lush voice here, made an outstanding studio recording with Herbert von Karajan and the Vienna Philharmonic. I’m less fond of her later one. At the time, it seemed to me to be a nearly perfect match of conductor and work, although his later recording disappointed me, too, but on his Decca CD (formerly an RCA LP), I think he finds the perfect balance of refinement and melodrama. Karajan once said that Price’s voice gave him goose-pimples, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he got them during the recording sessions. Kurt Adler (not to be confused with Kurt Herbert Adler), at the time the Met’s choral maestro, conducts a similar, if tamer, performance in 1962, and Price is almost as good for him as she would be for Karajan five months later with the advantage of retakes. Adler is very accommodating to his Cavaradossi, Franco Corelli, on one of his high-note-happy days—but they are awfully good high notes; he holds onto “vitto-o-o-o-o-o-riaaaah” forever but, sadly, “E lucevan le stelle” degenerates into a sloppy, desperate bid for applause (he gets 30 seconds’ worth). Still, he’s in great, ringing voice throughout the performance. In his own somewhat clumsy way, he projects virility and passion, which is what Cavaradossi is basically, about. As for Cornell MacNeil, he’s a Scarpia who can actually sing the role without shouting and still project the slimy, alternately fawning and bullying character of the violent, brutal man he’s portraying. It’s a pleasure to hear his powerful deep baritone voice applied with such discernment. A pity that he never made a studio recording. There are the usual competent Met comprimarios. The broadcast is monaural but so is the legendary de Sabata recording (Callas-di Stefano-Gobbi) with which it competes. I still admire that one above all others, but the stereo competition from Karajan (Price, di Stefano, Taddei) and Molinari-Pradelli (Tebaldi-del Monaco-London) is really formidable. After them, I think my choice might actually be this one, a broadcast that was well worth issuing. There is no libretto, but anyone who buys this set almost certainly has one already. FANFARE: James Miller