Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

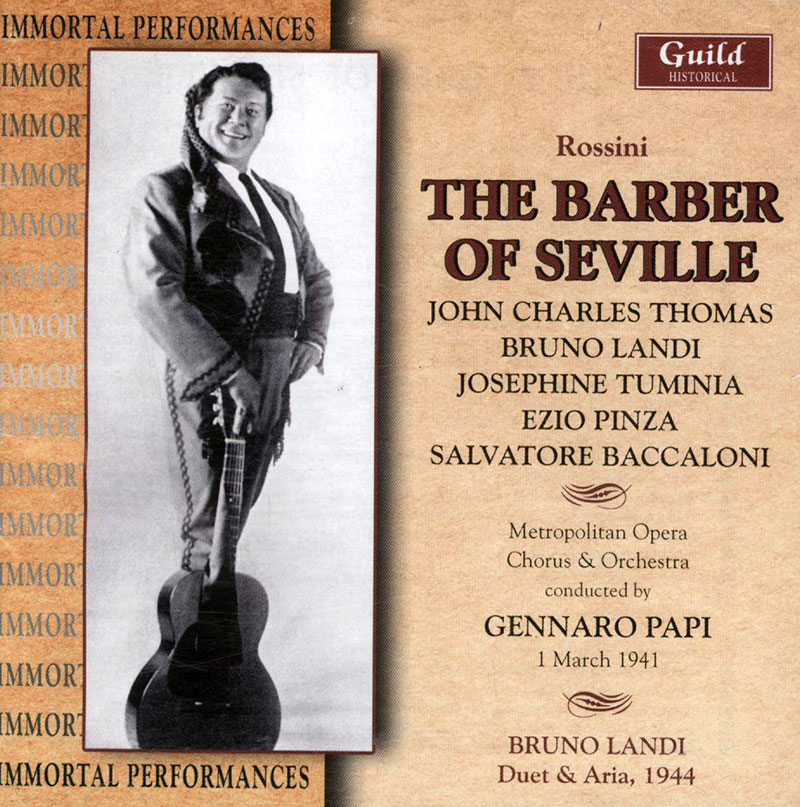

ROSSINI, John Charles Thomas, Ezio Pinza, The Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus, Gennaro Papi

Il Barber of Seville

International Record Review December 04 The Barber of Seville from the Met in 1941 boasts Pinza once more as Basilio, and the ripe Salvatore Baccaloni as Bartolo; but it is disabled by the Rosina of Josephine Tuminia, who had a Met career of almost unique brevity. The very fact that you are unlikely to hear a performance anything like this today is justification for hearing this one. … MusicWeb Thursday November 04 04 I’d read about such things, but not heard them. This issue gives us a peep into a lost world of opera production. Let me explain. Nowadays, when you put on the “Barbiere” and it’s like you get out your most recent Ricordi edition, carefully revised by Alberto Zedda and, taking your cue from Claudio Abbado’s classic DG recording, you pay scrupulous attention to every detail of the text, performing the music with elegance, refinement, vitality and a certain basic seriousness. Just as if it was by Mozart, in short. Sixty years ago the score (unrevised) was a peg for a theatrical show. It’s not just a question of cuts, though these become increasingly ferocious as the opera goes on, so that in the latter half of Act 2 we get not so much a performance as a whistle-stop tour. Against these are to be weighed frequent added lines, particularly by Baccaloni as Bartolo who ends most of his lines with a leering “eeeeh!”, mimics Rosina’s lines before actually replying to them and generally keeps up a sort of muttered commentary while others are singing their parts. But if Baccaloni is an extreme example, the others are not far behind. Whether these are personal gags on the part of the individual singers, or traditional accretions, I don’t know, but I am sure the basic practice was normal at the time. And then the notes themselves of the recitatives are scarcely respected. Entire sections are actually done as dialog, and in others the singing is a kind of Sprechstimme reminding us of Noel Coward or even of Rex Harrison’s performance in “My Fair Lady” which succeeded in raising “non-singing” almost to a noble art. But “My Fair Lady” wasn’t an opera. Furthermore, this style of comic non-singing even continues in the ensembles, much of the finale of Act One being resolved as semi-pitched “parlando”. One other “liberty” was traditional at the time; when Rosina has her singing lesson the music she takes out of her portfolio is not the aria Rossini wrote for inclusion at this point but Proch’s “Deh torna mio bene”. This lends unusual point to Bartolo’s comment that “the aria, all things considered, was pretty boring; music was something else in my days”. So where does this leave us? The set is claimed as valuable above all for Baccaloni and Pinza. As a theatrical performance Baccaloni must have been terrific – the public rock with laughter whenever he’s on stage. The voice is a firm and authoritative one though the singing as such – not that there is much – does not seem particularly remarkable. Pinza certainly was a great singer with a great voice and his account of “La Calunnia” is both histrionic and musical. It is perhaps the finest I have heard and rightly brings the house down. But, apart from this, Basilio does not have all that much to do in this opera. John Charles Thomas (1891-1960) was a Met stalwart, much appreciated as Germont and Amonasro. He is thoroughly at home in Italian and gives a comic pantomime performance along similar lines to Baccaloni’s. The voice itself seems a bit rough and cavernous. Bruno Landi (?1905-1968) was a genuine “tenore di grazia” with a sweet, honeyed line in lyrical passages and untroubled high notes (as we also hear in the Flotow extracts). Had he been born a generation or so later when the Rossini-Donizetti revival was in full swing his early training would have included agility too; as it is he pecks around the edges of many passages where modern ears demand accuracy. Today’s taste prefers a mezzo Rosina, though since Rossini provided variants and transpositions for a soprano Rosina we cannot actually say the latter is inauthentic. A soprano Rosina is better suited to the essentially frivolous conception of the opera current at the time and the Italo-American Josephine Tuminia has a bright and shallow soubrettish voice with easy coloratura and an ability to hold top Cs and Ds almost indefinitely. In its way it’s an attractive assumption of the role but others have given so much more and Tuminia, having sung Gilda and Rosina over two seasons, was not called back to the Met. Irra Petina is a caricatural Berta. The conductor Gennaro Papi was an old hand at the Met and his rough and tumble approach suits the pantomime conception well enough. Besides, it would have taken a Toscanini to impose order on his principals and insist on observance of the score, though the Leinsdorf recording of a decade or so later shows that the Met Barber Show, if still not quite embracing authenticity, was to get a beneficial spring-cleaning. Two things have to be said, though. The first is that this performance does enshrine an approach to the business of performing a comic opera the roots of which, if not the substance, go back to Rossini’s own days. In other words, he might have been sarcastic about some of the ways in which his notes were being treated but he might not have disowned the general style. The other is that people maybe enjoyed their evening at the opera much more than we do today. The Met public plainly never have a dull moment. This is a point to be weighed against the serious refinement of an Abbado. All the same, it belongs to an epoch when Rossini was patronised as the composer of a few good tunes rather than a musical dramatist not so far behind Mozart and deserving of the same respect. Still, the very fact that you are unlikely to hear a performance anything like this today is justification for hearing this one. The recording catches the voices reasonably well and is really remarkably good for what it is. The less said about the soprano in the Flotow duet the better and in Guild’s place I’d have issued only the aria. The booklet, like others in this series, has a detailed essay and mini-biographies of the singers and conductor. It’s a pity they manage to spell Rossini’s name wrongly (“Giaocchini”!) twice over, on the back cover and under his portrait, but there is a mystery to clear up since both the Concise Grove and the Italian Garzanti encyclopedia spell it “Gioachino” while the Ricordi score prefers “Gioacchino”. The double C is normal in modern Italian (the name is equivalent to the German “Joachim”) but was not so in Rossini’s own days. Christopher Howell