Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

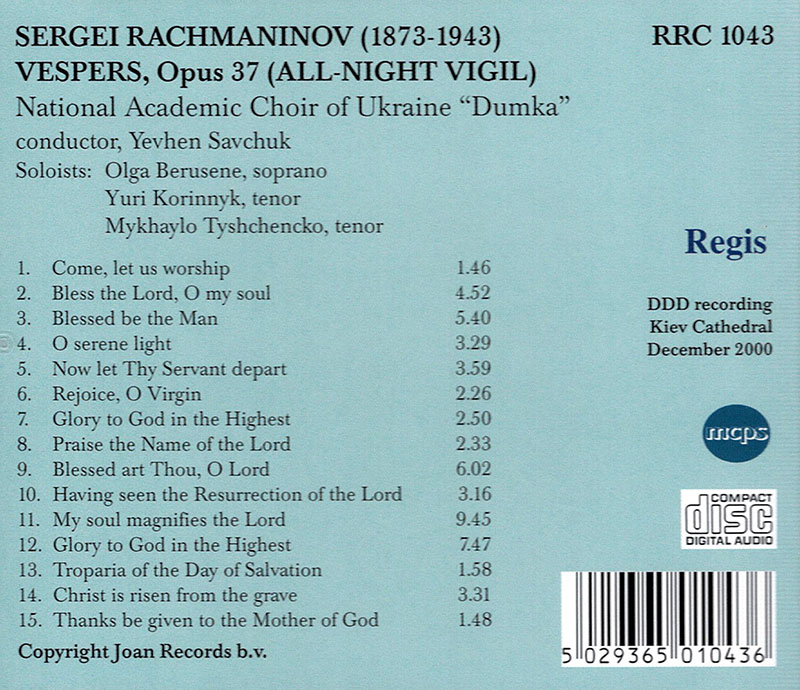

RACHMANINOV, National Choir of Ukraine 'Dumka', Yevhen Savchuk

Vespers Op.37 ('All NightVigil')

- 1. Come, let us worship 1.46

- 2. Bless the Lord, O my soul 4.52

- 3. Blessed be the Man 5.40

- 4. O serene light 3.29

- 5. Now let Thy Servant depart 3.59

- 6. Rejoice, O Virgin 2.26

- 7. Glory to God in the Highest 2.50

- 8. Praise the Name of the Lord 2.33

- 9. Blessed art Thou, O Lord 6.02

- 10. Having seen the Resurrection of the Lord 3.16

- 11. My soul magnifies the Lord 9.45

- 12. Glory to God in the Highest 7.47

- 13. Troparia of the Day of Salvation 1.58

- 14. Christ is risen from the grave 3.31

- 15. Thanks be given to the Mother of God 1.48

- National Choir of Ukraine 'Dumka'

- Yevhen Savchuk - conductor

- RACHMANINOV

Rachmaninov Vespers ("All Night Vigil") Prior to the introduction of Western-style musical notation on horizontal staves, Russian chant, known as znamenny, was shown in books by a series of upward and downward movements above and below the Gospel texts. These books dating from the eleventh century had been brought to Russia from Byzantium by Greek singers and prior to their manufacture of the books, the chants were passed down orally. Predictably there has been a huge problem in deciphering these marks, which are believed to represent the movement of the conductor's hand (indicating the required expression) more than a series of musical notes. That we can decipher them at all is due to Tikhon, a patriachal treasurer (died 1706) who managed to transcribe some of these chants onto staves prior to their disappearance from Russian churches during the Great Schism that occurred in Peter the Great's reign, when like much of Russian societv, western influence was introduced and indeed encouraged. Dissenters from this new church living beyond the Urals and in other distant parts of Russia, known as Old Believers, continued to use znamenny but elsewhere Western notation became the norm. In 1772 the Holy Synod allowed an antiquarian named Byshkovsky to publish some books of old chants using Tikhon as his model. Interest was further sustained into the late nineteenth century when Stepan Smolensky, director of church music at the Synodal School and the Moscow Conservatoire, encouraged his students, (among whom were Scriabin and Sergei Rachmaninov), to examine these chants and the notation, known as neumes as part of their studies in composition. That others of the same generation as Smolensky were interested in the old chant (and in the traditions of the Orthodox church in general) can be seen from Tchaikovsky's writing in 1877 9 also love Vespers. To stand on a Saturday evening in the twilight in some little country church, filled with the smoke of incense; to lose oneself in the external questions, whence, why and whither; to be startled from one's trance by a burst from the choir; to be carried away by the poetry of this music; to be thrilled with quiet rapture when the Royal Gates of the Iconostasis are flung open and the words ring out, `Praise the Name of the Lord' - all this is infinitely precious to me! One of my deepest joys!' Tchaikovsky's appreciation stemmed from the efforts of eighteenth century musicians of the Court Chapel to set the Psalms to music, but in his Liturgy, of St John Chrysostom he attempted to get closer to the Byzantine sound. Whilst this work is noticeably more restrained than his usual style, it cannot be said that he showed true awareness of the znamenny chant and it was not until Rachmaninov (1873 - 1943) composed his Liturgy in 1910 and the Vespers (more properly called the Allnight Vigil) in 1915, that a modern understanding of these old chants was reached. Sergei Rachmaninov's decision to move his family to the relative peace and quiet of Dresden in 1906 and away from the violence and suppression which was increasingly engulfing Russia gave rise to some of his finest orchestral pieces such as the Second Symphony and The Isle of the Dead. Upon his return from Dresden he spent ever more time at his wife's family estate Ivanovka, in the southern steppe. Able to compose in relative seclusion his style became more inward-looking and an interest in religious music which he had developed whilst a student in Moscow was rekindled. With the Liturgy Rachmaninov attempted to set the lengthy service in its entirety but was not entirely satisfied with the result. Neither were the ecclesiastical authorities, for although this work was unlike any other composition by Rachmaninov to date, his music was nevertheless deemed too beautiful for performance in a church context. Five years later he made an attempt to improve upon the style of the Liturgy, and in the All-night Vigil he utilised znamenny plainchants in six of the canticles (numbers 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 14). Two canticles use chant stemming from Greece (2, 15) and two from the Kiev region (4, 5) and the remainder are original compositions by Rachmaninov, called by him 'conscious counterfeits'. Rachmaninov achieves a proper ecclesiastical sound at the outset by means of parallel motion between parts and with modal chord progressions. The second canticle (Psalm 104) features the solo contralto alongside the massed male voices interspersed with brighter sound from the women. The canticle closes with one of many famed descents for the basses. Psalms 1 - 3 provide the texts for the following canticle. 'tenors and altos provide the narrative to which the entire choir responds with 'Alleluia'. Although these Alleluia's rise in tone, they also get progressively quieter. The Vesper hymn '0 Joyful light of Heaven' has the tenors singing a descending fourth followed by an upward climb, being joined by first the lower women's voices, then the basses and finally a solo tenor. The Nunc Dimittis follows with the solo tenor supported by rocking ostinatos. After the central climax the basses slowly sink to a bottom D flat. It was this section of the work that Rachmaninov wished to have sung at his funeral. A lovely meditative Ave Maria follows, bringing the Vesper section of the All-night Vigil to a close. The Russian Orthodox Vigil is observed on the eve of holy days, beginning at six o'clock on a Saturday evening and continuing through to nine o'clock the following morning. The remaining nine pieces are therefore classed as Matins. These open with a rich setting of the Gloria showing, (aside from the close), a gradual change from contemplation to celebration. No. 8 (whose text is similar to Psalms 134 and 135 - Laudate Dominum) contrasts the higher voices singing quietly against an intoning znamenny chant from the altos and basses. No. 9, a Resurrection hymn, forms the dramatic core of the work and begins harshly before becoming more melancholy. Following the tenor's announcement of glad tidings the singing becomes more animated. In No. 11 male and female voices are pitted against each other. similarities between this chant and the opening of Piano Concerto No. 3 have been noted by Barrie Marlyn in his biography of the composer (1990). A lengthy Magnificat follows with a melody moving up the voices and including a hymn of praise to the Virgin for the higher voices. A further setting of Gloria recalls music from the third canticle and makes much play of wide rhythmic and dynamic contrasts. The following two sections are both Resurrection hymns which return to the more rapt devotional textures of the Vespers' half of the All-night Vigil. The final section, derived from Greek chant, is a joyful hymn to the Holy Mother. Rachmaninov dedicated this work to the memory of one teacher, Smodensky, and sent it, as always, for approval to another teacher Taneyev, who wrote back encouragingly. Sadly it was to be the last score Taneyev received as he died four months afterwards. The 1917 Revolution effectively ended any prospect of performance in Russia for some considerable time whilst outside Russia Rachmaninov faced insuperable problems raising a choir able to do it justice. © 2001 James Murray