Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

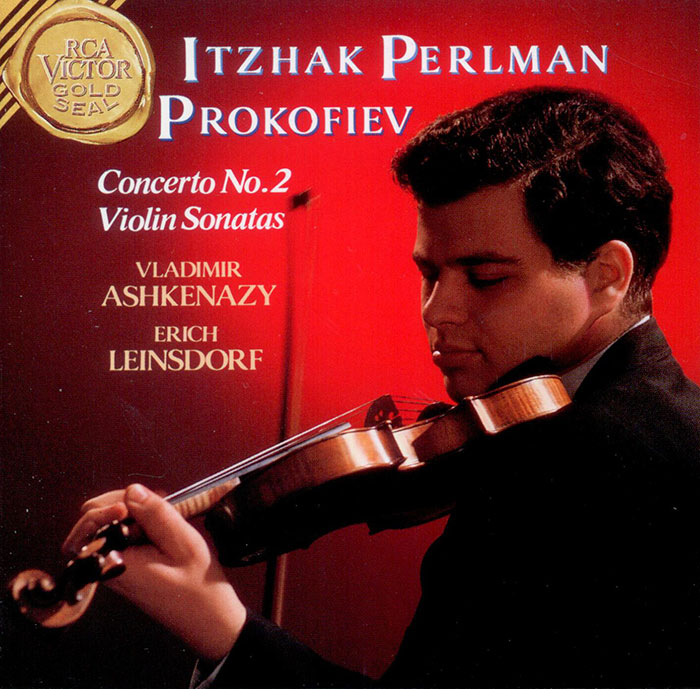

PROKOFIEV, Itzhak Perlman, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Erich Leinsdorf, Boston Symphony Orchestra

Violin Sonatas; Concerto No. 2

- Itzhak Perlman - violin

- Vladimir Ashkenazy - piano

- Erich Leinsdorf - conductor

- Boston Symphony Orchestra - orchestra

- PROKOFIEV

For a startling premonition of Arvo Part's unmistakable brand of heterophony, cue 3'16'' into track 1 of Kontrapunkt's disc See album (or 3'09'' into the same track on the RCA reissue) and the evidence is clear as day: a weeping incantation that, if taken out of context, could easily have grown among the pages of Part's more recent instrumental works. Eight years in the making, Prokofiev's F minor Sonata—surely his greatest chamber work—opens bleakly, then flowers to harmonic richness before switching to a sharp-edged Allegro brusco, a deeply introspective Andante and a closing Allegrissimo that recalls (or anticipates, depending on its precise chronology in Prokofiev's thinking) the finale of the great Eighth Piano Sonata. David Oistrakh was the work's dedicatee and his recordings of it (there have been at least four over the years, of which only one on Praga—(CD) 250041—is currently available) exhibit such tonal and interpretative distinction that any newcomers will need to summon all their powers to compete. Of the two performances under review, Perlman's is the more securely focused—an immensely assured, sweet-centred reading, delicate where needs be (the ''wind in a graveyard'' passages of the first movement, for example) and yet with a Heifetzian resilience that both sonatas willingly respond to. Nikolai Madojan, a highly gifted product of Zacha Bron's school in Novosibirsk and still only in his early twenties, favours more neutral colouring but has a natural feel for the 'right' inflexion: of the two performances, his is the more thought-provoking (in that respect, Madojan is more akin to Kremer or Oistrakh than to Perlman), while Perlman's has the more rounded tone production. Furthermore, both pianists are ideally suited to their partners—Ashkenazy being the more incisive and percussive, Westenholz refreshingly tender-hearted and imaginative. When it comes to the delightful Second Sonata—of rather less import, and a second-hand utterance (the original was for flute and piano)—Perlman and Ashkenazy play with astonishing virtuosity and here their visceral virtues win hands down, especially in the Scherzo. Madojan and Westenholz are more restrained and although their innate musicality pays high dividends (especially as heard immediately after the intensely private Melodies), the second and fourth movements are marginally under-characterized. Kontrapunkt's CD is a good one and will not disappoint those who are attracted by the programme. Kremer and Argerich offer an identical coupling, but their distinctive bravura (cerebral as well as physical) may not be to everyone's taste. Oistrakh's version of the First Sonata is essential listening, although Praga's recording is less than ideal, while Viktoria Mullova offers a first-rate alternative account of the Second Sonata. However, the first-time collector has a real bargain in RCA's mid-price coupling: it may not dig quite as deep as some rivals, but the playing has real class, the recording is clean (if rather brittle) and there's a substantial bonus in Perlman's accomplished 1966 version of the Second Violin Concerto, where Leinsdorf and the Boston Symphony trace and characterize the score's every subtle detail—especially among the woodwind. That, for me, is the disc's most indelible interpretative feature. -- Gramophone [9/1994]