Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

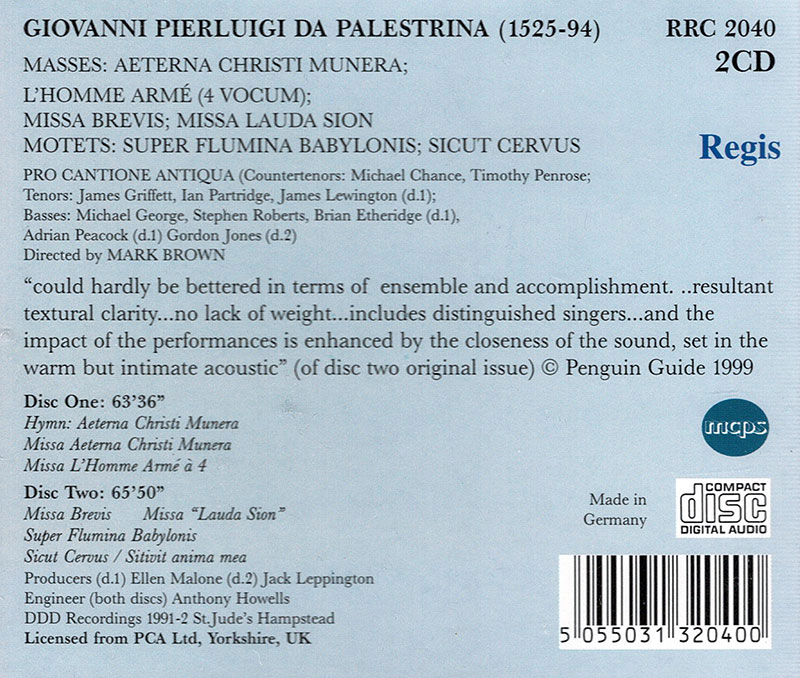

PALESTRINA, Mark Brown, Pro Cantione Antiqua

Masses & Motets

Palestrina: Hymn: Aeterna Christi Munera / Masses: Aeterna Christi Munera / L'Homme arme a 4 / Missa Brevis / Missa Lauda Sion / Motets: Super Flumina Babylonis / Sicut Cervus The Proper for Aeterna Christ Munera is that of St. Andrew the Apostle, and that for Missa L'homme arme is Commune unius Martyris non Pontificis. Palestrina's understanding and love of plainchant clearly shows in the textural quality of his melodic writing, which is a perfect and subtle match of verbal and musical accentuation, to the extent that bar-lines are sometimes a barrier to a full appreciation of his achievement. Many times he based his masses and motets on plainsong, but he also occasionally used secular material, and the two L'homme arme masses are the best known examples. The 4-part mass heard here was published in his Fourth Book of Masses (1582), but would have been composed much earlier (though later than the 5-part setting which appeared in the Third Book). The tune had been well-known throughout musical Europe since the middle of the 15th century, and attracted at least 31 mass settings by almost as many composers, including Dufay, Ockeghem and Carissimi. It is a robust, symmetrical tune, offering good opportunities for polyphonic treatment. The words, from a late 15th century Neapolitan manuscript, do not, however, present similar liturgical possibilities. They refer to a crusade against the Turks: "Fear the armed man; word has gone out that everyone should arm himself with a hauberk of mail." The song appears in every section of the mass, and its strength and simplicity are reflected in Palestrina's treatment. The opening Kyrie, for example, has the theme stated boldly in the Cantus part and echoed three bars later by the bass (with a final statement in the tenor), while alto and tenor elaborate on different parts of the melody. The second Kyrie has the altos part using the second stanza of the tune as cantos firmus, and in the Gloria each voice in turn states the melody, the altus a fourth lower. Palestrina's method of moving to new material by means of a homphonic cadence is frequently in evidence here, as, at Gratias agimus, tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam, leading into Domine Deus. The Credo is longer than that of Aeterna Christi Munera. There is less overlapping of words, and his setting of Est incarnatus est is entirely homophonic compared to the imitative polyphony at this point in the later mass. The same is also true of Est iterum venturus est. The Benedictus is, as usual, in three parts, but the Hosanna preceding it is notably shorter (barely four bars) and the following one notably longer than in Aeterna Christi Munera. The variety of colour is remarkable too, the high-voiced Benedictus trio contrasting with the usual addition of a second bass in the lovely 5-part Agnus Dei II. Palestrina used every available form and technique in his masses. Some were freely composed, some used the (by then) old-fashioned cantus firmus, some were `paraphrase' masses and some, like Lauda Sion, were in the form he employed most (54 times), that of `parody' or imitation, based on either his own, or other composers' material. Both the masses on the first disc are "paraphrase" masses, that is to say, they take existing monodic material and treat it polyphonically. Aeterna Christi Munera is based on the Matins hymn for the Common of the Apostles (heard before the Mass), variations of which date back to the 12th Century. Palestrina closely follows the syllabic version known to him, and its three themes occur in all voices throughout the mass; the first in Kyrie I, Sanctus, Hosanna and Agnus Dei, the second in Christe Eleison, Domine Deus, and Benedictus, and the third in Kyrie II and Pleni sunt celi. Moreover, the ABCA form of the hymn is echoed in the mass. The Sanctus, for instance, doubles that form, the Hosannas representing the return of A, and the second BC the trio Benedictus. The second Hosanna is an extended and more elaborate version of the same material used in the first, a feature which also occurs in the 4 part "L'homme arme" mass. Aeterna Christi Munera was published in 1590 in the Fifth Book of Masses, and its ingenuity, clarity and simplicity, epitomise the refinement of Palestrina's late works. It is also extremely beautiful, and reminds us that in his letters to Duke Gonzago, he repeatedly stresses the importance of the sound of the music. It is a short mass, shorter even than the Missa Brevis, and the Credo, despite the length of that text, is, as Jeremy Roche has pointed out, not much longer than a lengthy motet. This brevity is partly achieved by repeated overlapping of words, a feature also of the Gloria, and much fugal treatment which further emphasises the strong thematic links. If Palestrina's masses were once described as `vocal symphonies' (he wrote no instrumental music), this one is very much a string quartet, and one that had excited the attention of other composers, from Palestrina's contemporaries, to Beethoven and Debussy. Henry Coates has even suggested that Wagner's intensive study of the work in Dresden led to the beginnings of his leit motif system. Other writers have noted the way Palestrina's fugal techniques have influenced those of later composers, such as Bach in his Choral Preludes, though, unlike Bach, Palestrina's expositions present a series of related ideas rather than the development of one. Above all, however, Palestrina's inspiration, the balance and symmetry of his work, springs from his deep familiarity with, and understanding of, his texts. He set the Ordinary so many times (104 published masses) that the liturgy became less a restrictive framework than a constructive musical element, so that the words became phonetic material upon which he lavished his skill and imagination. Stravinsky, writing about his own setting of the Latin text of Oedipus Rex, puts it precisely: "The composer can concentrate all his attention on the primary constituent element of the text, that is to say, on the syllable. Was not this the method of treating the text that of the old masters of austere style? This too, has for centuries been the Church's attitude towards music, and has prevented it from falling into sentimentalism and, consequently, into individualism." The Missa Brevis falls into the first category. It was published in 1570 in his Third Book of Masses (which also contains his earlier 5 part L'homme arme mass) and was clearly as popular then as it is now, as much for its ingenious musical qualities as for its suitable liturgical length. "fhe title means just what it says, though other explanations have been offered; that the nota brevis is the first note of the mass, or that `brevis' could be synonymous with `sine nomine', a title sometimes given to works based, as this is, on original motifs. The resemblance of some of the Missa Brevis themes (except the Benedictus) to those of a motet by Goudimel, Audi filia, throws doubt on to the latter supposition, though, in fact, several themes are undoubtedly derived from the fragments of plainsong. Indeed, it is a remarkably melodic mass. Palestrina's technical perfection and the restraint and serenity of his writing sometimes make one forget that he himself set most store by the sound that music makes. In a letter to the Duke of Mantua in the same year as the publication of this mass, he offers practical advice about the Duke's own composition: "I have marked a few spots where it seems to me that the music could have a better sound;" and later: "the strict interweaving of imitative parts sometimes obscures the text so that hearers cannot enjoy it as in less strictly written music." This is not dry, academic criticism, it is a reminder that music is to be heard, not seen, that technique is the means, not the end. For example, the theme of Christi Eleison reappears wonderfully as the Saviour bearing the sins of the world in the Gloria, and again in the Credo, at the words Crucifixus etiam pro nobis, but it is our ears that tell us this, not our eyes. Both the Gloria and the Credo have an attractive simplicity, the latter rather less homophonic than the former, and the Sanctus has cascades of descending figures against the first three notes of the Kyrie theme, but even finer melodic beauties are to be found in the delicate three part Benedictus. Aguus Dei I is equally beautiful, and in Agnus Dei II, Palestrina is at his greatest, an extended canon for cantus I and If as part of a 5-voice fugal exposition. The Chant used for the Proper of the mass is In Nativitate Domini with appropriate transpositions, since the Ordinary is sung at a pitch which enables what were known as sopranists to sing the cantus line. The same is true of Missa Lauda Sion, the Proper chant for which is that of the Feast of Corpus Christi. This mass, from the Fourth volume, published in 1582, is a parody based on Palestrina's own motet of the same name written in 1563. The sequence Lauda Sion comes, of course, from the mass of Corpus Christi, and Palestrina made two 8-part motet settings; the one on which this mass is based was not published in his lifetime. The Missa Lauda Sion is about the same length as Missa Brevis, but shows different aspects of the composer's genius, though it is no less beautiful. Palestrina's melodic line usually confines itself almost exclusively to movements of no more than 3rds, 4ths, 5ths and ascending minor 6ths. In the alto part of both Agnus Deis however, there are several ascending octave leaps. There are many other striking moments; the contrary motion entry in the Gloria; the beautiful Qui Tollis; the lively decorations at Et ascendit; and the characteristic rhythmic variation of the same brief theme of both cantus and tenor parts of Aguus Dei I, which gives the music both subtlety and vitality. The Benedictus is, like the Missa brevis, in three parts, and not for the first time, Palestrina gives some of his loveliest music to the tenor (he was one himself). Also, not for the first time, he lets himself go in Agnus Dei II, keeping a particularly lovely effect of ascending and descending figures for the very end, at the words Dona nobis pacem. Both the motets, Super Flumina Babylonis, and Sicut Cervus, come from the 1581 Book of Motets (the 5th of seven books he published), and are masterpieces of the highest order. As with the masses, Palestrina's object is to draw the listener's attention to the significance of the text, and the wider variety of texts in he motets naturally elicits a wider variety of descriptive expression. His method, however, is the same. A phrase, or a sentence, inspires a musical idea taken up by each voice, and this process, sometimes overlapping, more often broken by cadence, continues throughout the work. Super Flumina Babylonis is a perfect example. It is the poignant lament of a captive nation, and the long opening phrase, moving almost entirely in major and minor seconds, immediately suggests desolation. Cadences on the words Illuc sedimus lead to the central section, a tense development of the setting of Dum recordaremur tui, Sion, an evocation of anguish unsurpassed anywhere in music, joined seamlessly to the imitative entries on n salicibus, and, finally, Suspendimus organa nostra. The opening theme of Sicut Cervus, written to be sung at the blessing of the baptismal font on Holy Saturday, is an instance of the almost mathematical melodic balance typical of Palestrina. The treatment of the words in the first part is totally fugal, each new section overlapping the last, and the second part, Sitivit anima urea, is almost entirely canonic. The reshness and grace of this motet alone justify Vincent; Galilei's saying of Palestrina "quel grande mitatore della natura". Peter Bamber 1991-2