Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

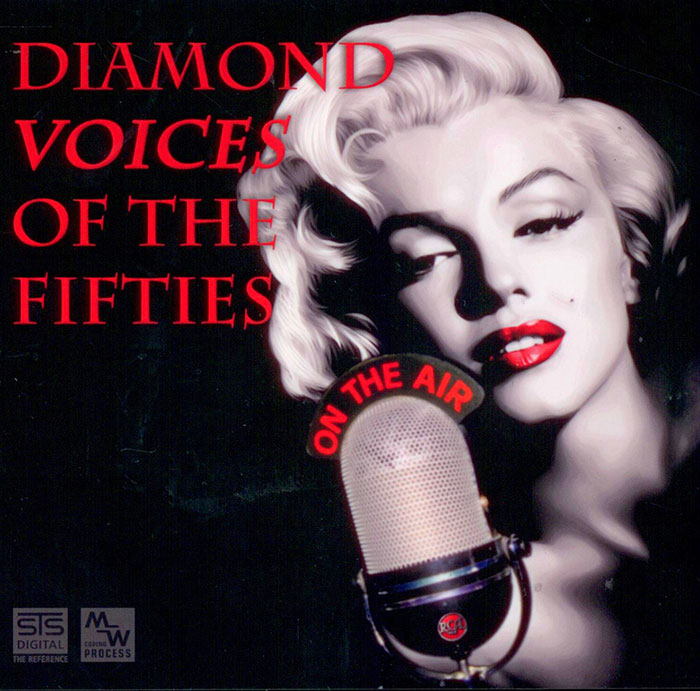

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

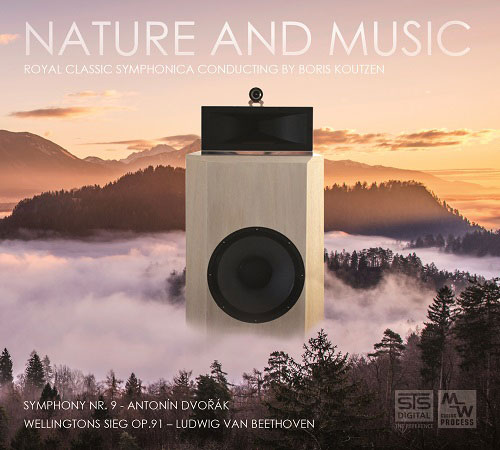

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

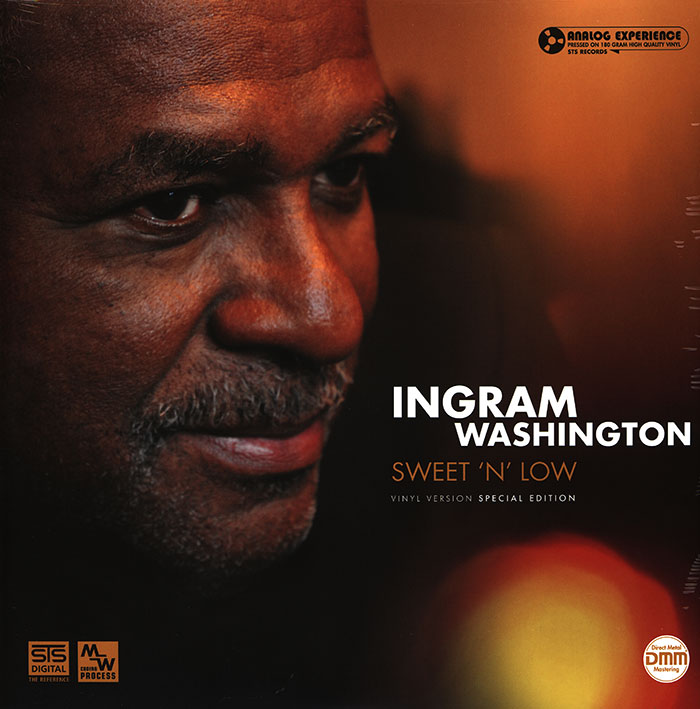

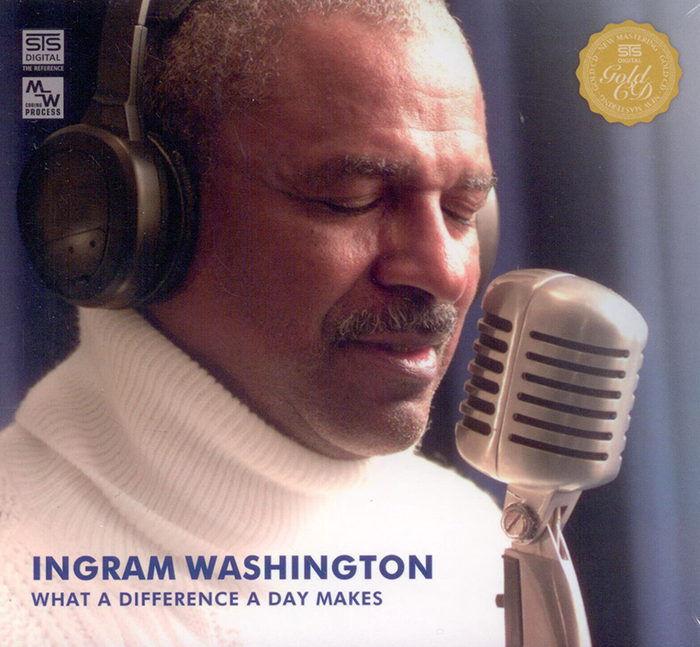

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

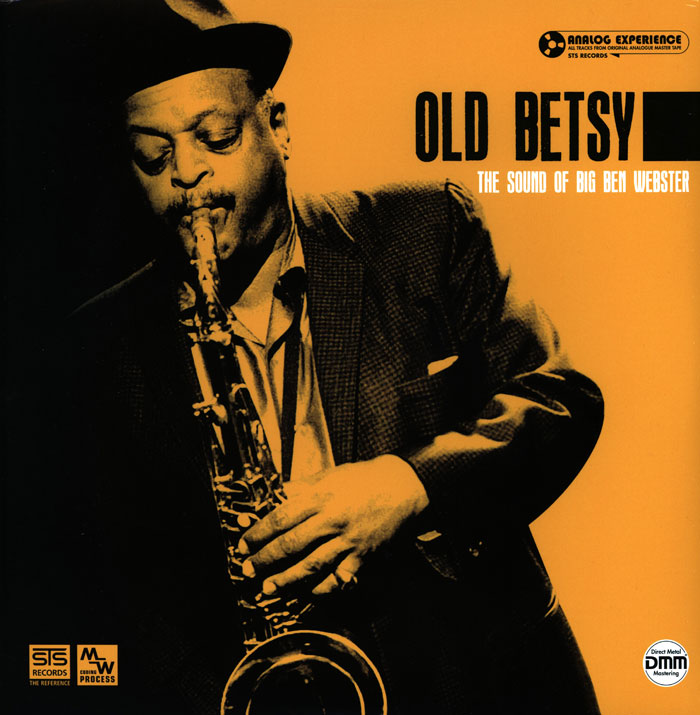

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

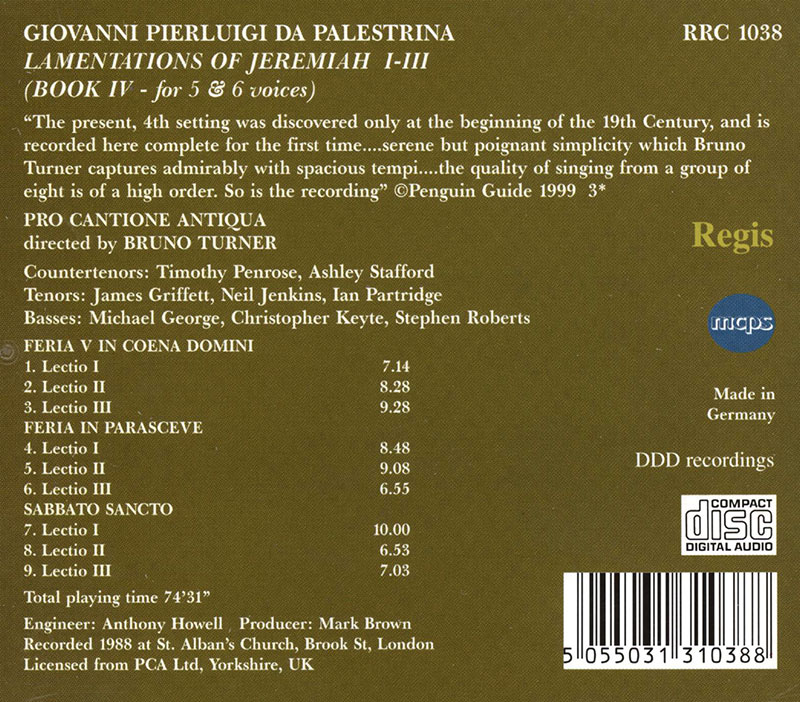

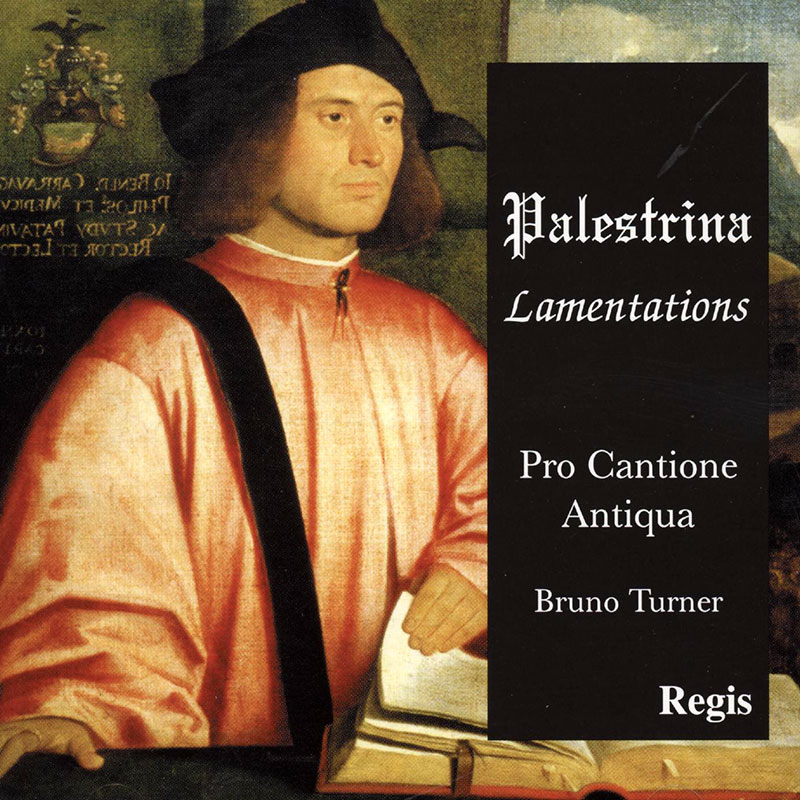

PALESTRINA, Pro Cantione Antiqua, Bruno Turner

Lamentations of Jeremiah the Prophet, Book IV for 5-6 voices

- Pro Cantione Antiqua - group

- Bruno Turner - conductor

- PALESTRINA

"recorded here complete for the first time... serene but poignant... quality of singers of a high order" Penguin Guide 3*) Palestrina: Fourth Book of the Lamentations of Jeremiah RRC 1038 The name of Palestrina is inextricably bound up with our images of the Counter Reformation, the Tridentine Latin Mass, the revision and perfection of the Roman liturgy. Palestrina has always been regarded as the ideal Roman composer, the musical paragon of that City. He is part of that link between Heaven and Earth which is the essential nature of the great Christian liturgies, now abused and in decline in the West. settings of these harrowing texts. The Hebrew letters are composed in countless ways, from tender sadness to the most majestic grandeur. This is another Palestrina. The harmonies are frequently minor, the melodic intervals are often minor, even when the tonality is in our terms major. There we have the sad lamenting master following in the tradition of the great Spanish composer Morales whose work Palestrina knew intimately. It has been unfashionable to proclaim these sentiments and equally so to persist in placing Palestrina at the centre of Catholic religious music. Musicologists tend to view him as just one important composer in a century crowded with talent and not short of men of genius. Yet, despite Palestrina's assumed hegemony of his time and all that has been written in nearly four hundred years, his music is only a little known to choirmasters and listeners alike. To most of us, his music is at least blandly perfect, and, at its frequent best, glorious, grand, brilliant and, as it were, shining with bright harmony. The great masses Assumpta est Maria*, Papae Marcelli *, and Ecce ego Johannes, resplendent motets like Surge illuminare Jerusalem, and the great cycles of Offertories and Hymns for the year's feasts give us an impression of major keys, of victory and joy. Palestrina was a prolific composer, there are more than twelve columns listing his works in the New Grove Dictionary of Music. Among them, passed over briefly in its articles and other books, are the cycles of Lamentations written for the First Nocturns or Matins on each of the three last days of Holy Week. Rarely performed, still less recorded, they have been neglected on the grounds that they are liturgically functional music in the homophonic falsobordone style, choral recitation interspersed with short sections of admittedly beautiful melismatic settings of Hebrew letters-Aleph, Beth, and so on-that preface the verses of Jeremiah's laments. The scholars do not appear to have read this great body of music with its true sound in their minds. They have missed the variety and subtlety of Palestina's deeply meaningful Not just once but five times Palestrina set the Lamentation Lessons for the Tenebrae service (Matins followed by Lauds) on Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. He published in 1588 a set that is his simplest; the others remained in manuscript, music preserved for the Roman choirs with which the composer was associated. Palestrina certainly wrote one of his sets in 1574 for the Sistine Chapel and had just completed another full cycle for the Cappella Giulia. Early last century the enthusiast and scholar Pietro Alfieri unearthed a collection which has now become known as Palestrina's Fourth Book of Lamentations. It is kept in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana and is now classified as Codice Ottoboniano 3387. This is the great cycle recorded here in what is the first full modern performance. It is a great amount of music and should really be heard in sections, as it is written, for the Triduum sacrum, the last three days of Holy Week. The Lamentations are written in nine Lessons, three for each of the days. Each Lesson is subdivided into verses, which are preceded by a letter of the Hebrew alphabet in the old plainsong settings, and have a short "wailing" motif. In Renaissance polyphonic compositions the authors wrote more or less elaborate contrapuntal vocalisations. Palestrina does exactly this, varying his material, his voices and their spacing with infinite variety. Musically, these `letters', Aleph, Beth, Vau, etc, serve as points of repose, interludes separating the verses in which the writing is densely packed with words, by no means always homophonically, often with strongly profiled motifs in imitation voice by voice. Emotionally, the Hebrew letters are enshrined in the most moving and awesome sounds, much more than the conventional plangent. Palestrina seems to have written them as little private sound worlds in which the listener may be swept up in the contemplation of the Passion. The Old Testament laments of Jeremiah are in the liturgy of the passio et mors Christi as symbols of the Church's grief and its call for redemption. The Lessons with the added (post-Biblical) call Jerusalem, return to the Lord thy God'. In these endings, Palestrina always seemed to contrive a feeling of strength, even a hint of optimism. At the very last, on Holy Saturday, he seems really to anticipate Easter. This Fourth Book of Lamentations is notated in the standard clefs of the Renaissance, and because it was for circulation in Rome, if not actually for one particular choir, we have assumed it to be for adult male voices including the traditional sopranists (falsetti). It is more likely that castrati were often used especially in the years after Palestrina's death. Certainly, Palestrina would have expected his music to be sung by a few expert choirmen, varied Lesson by Lesson, chosen from the singers present, basses and baritones, high tenors (altus) and the sopranists (many of them falsettists from Spain). His music in this Tooth Book' is mostly for five voices with sections for three and four. In the Good Friday Lesson II he employs six voices, and again six to great effect in the third and final Lesson on Holy Saturday, when, for the first time, he has two falsetto parts brightening his sounds. When we listen to this great collection in our modern way, just as music, even as nonbelievers, we might spare a thought and a little effort to the appreciation of its true purpose and context, also to the residual relevance of these words and music to our own times. Notes by Bruno Turner.