Logowanie

TYDZIEŃ z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

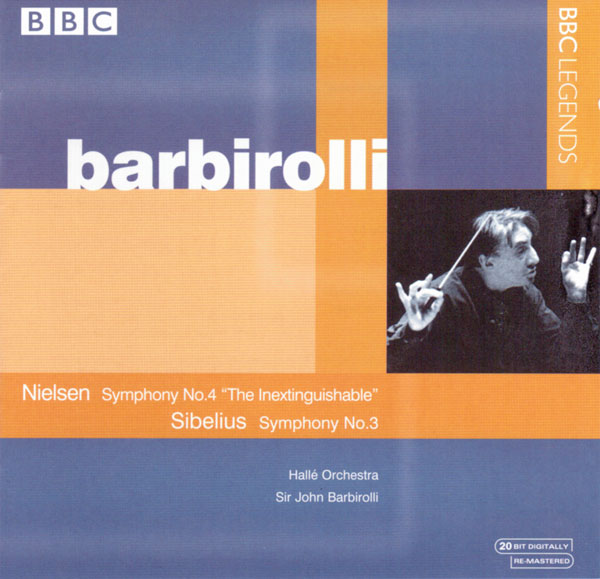

NIELSEN, SIBELIUS, The Halle Orchestra, Sir John Barbirolli

Symphony No. 4 / Symphony No. 3

The frenetic immediacy of Nielsen’s Fourth Symphony (30 July 1965) under Sir John Barbirolli (1899-1970) compels our undivided attention from the blazing opening: the composer’s harmonic and textural syntax remains distinctive even after half a lifetime of performance-familiarity under the likes of Bernstein, Blomstedt and Markevitch. In England, Nielsen’s energetic and muscular sound was unknown until 1950, then George Weldon took up the mantle of apostle. Having first mastered the Fifth Symphony, Barbirolli turned to the flamboyant Fourth, with its opportunities for the conductor and his Halle players to demonstrate their prowess. After the various torrents of the first movement, its graduated coda is an audible, ingenuous delight. The playful woodwind antics of the second movement, punctuated by string pizzicati, allow the Halle principals to demonstrate their airy textures, and the sound might suggest a moment or two from Mahler. The mood alters drastically in the slow movement in the form of an andante – a feverish, contrapuntally agonized movement not far from Bartok. As it becomes more martially inclined, the Halle trumpets and tympani make some pronounced points of their own. The frenzied segue to the final Allegro unleashes a yearning urgency with barely a breath for relief. The Halle tympanist earns his pay several times over with riffs worthy of Vachel Lindsay‘s poem Congo, while the Halle strings execute metric shifts and spasms of singular ecstasy. The coda enjoys a splendidly heroic peroration, to which the audience cannot help reacting long before the last chord has decayed. I have been ever in admiration of Barbirolli’s Sibelius, my having learned the elusive Third Symphony (which Karajan consistently avoided) via Sir John’s EMI LP and his entire cycle; another strong voice in this symphony was Paul Kletzki. Barbirolli called the 1907 C Major Sibelius’ “transition symphony,” aware that it marked a departure from the Russian (viz. Tchaikovsky) influence in the composer’s symphonic sense of both structure and harmonic syntax, especially as Debussy became a factor. The performance (8 August 1969) follows the tradition Barbirolli inherited through scrupulous examination of the score and of recorded performances by Robert Kajanus, the first of the great Sibelius acolytes. Vividness of execution and breadth of conception mark this dynamic realization, an almost Elgar-like girth and nobility of line. The heart of the symphony, the slow movement, Barbirolli urges along gently, without excessive dawdling. Gorgeous string ensemble from the Halle matched by equally pointed woodwind ensemble. The last movement develops an insistent march punctuated by flaring trumpets and busy bass fiddles. The tympanic rolls quite sweep us along between ether and Roman triumph. – -Gary Lemco