Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

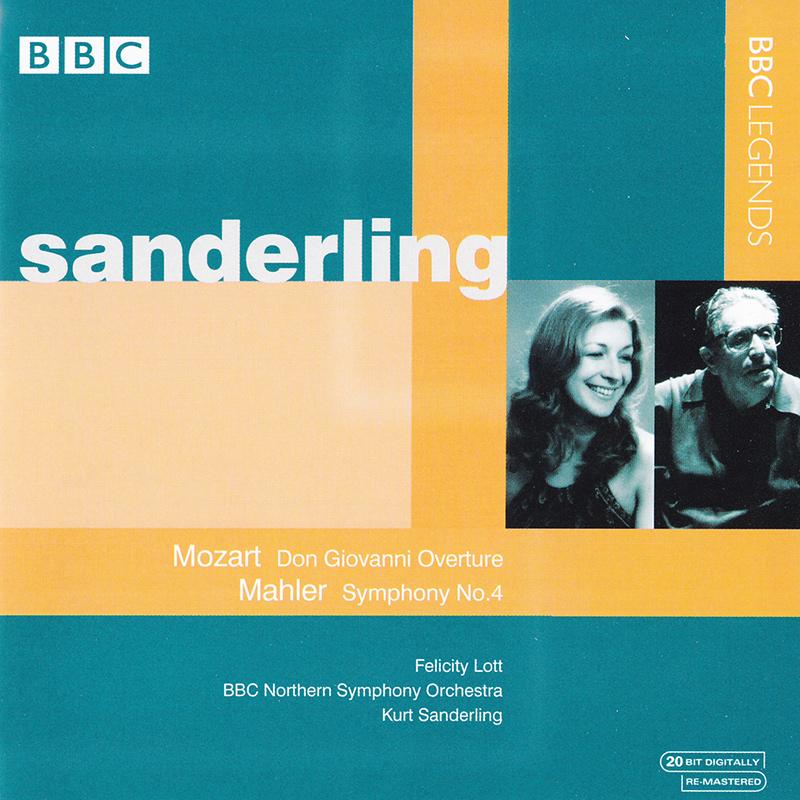

MOZART, MAHLER, Felicity Lott, BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra, Kurt Sanderling

Don Giovanni Overture / Symphony No 4 in G major

- Felicity Lott - soprano

- BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra - orchestra

- Kurt Sanderling - conductor

- MOZART

- MAHLER

Last year I reviewed Sanderling’s performance, with the same orchestra of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony. That impressive performance was made in 1982. Five years earlier, before the orchestra had been renamed BBC Philharmonic, Sanderling led them in this account of the Fourth symphony. I was interested to discover that the important violin solo in the second movement of the symphony is played by the orchestra’s then-leader, Dennis Simons. I had the pleasure of meeting Mr Simons on a couple of occasions in the late 1970s when he played concertos (Bruch and Brahms) with the amateur orchestra in which I played at that time. It’s nice to be reminded on this disc of his fine playing. I remember him also as a charming, courteous man and that comes across in the warm recollections of Kurt Sanderling which he contributes to the booklet note accompanying this release. The note also includes some comments by Kurt Sanderling’s son, Thomas, himself a distinguished conductor. He points out that the “psychological dualism” of this symphony fascinated his father. That will come as no surprise to those who have read Tony Duggan’s absorbing essay on this work in his synoptic survey of the Mahler symphonies on disc. As Tony writes: “Since this is Mahler's shortest symphony and the one with the prettiest and most tuneful textures it's earned its place as his most popular and approachable. But be careful about viewing it as entirely untroubled. There are dark shades cast on the filigree textures and piquant colours.” The impression I have is that Sanderling, for all the virtues of his performance, is perhaps a little too severe. I miss the charm, the naïveté, that other conductors have brought to this score. The first movement sounds quite straight and sober here. There’s not a great deal of evidence of Viennese rubato and the reading struck me as being somewhat lean and classical. The rhythms are well sprung and the music moves forward - quite briskly so at times. I think I’d sum up the reading as clear-eyed and purposeful. The second movement is light and dexterous. Dennis Simons’ violin solos are characterful without any unwelcome exaggeration. Mind you, it’s only fair to say that he’s not the only good soloist we hear. In this movement, and elsewhere, the woodwind principals and the first horn all distinguish themselves at regular intervals. Sanderling brings out the grotesque side of the music well but there are also some welcome examples of warmth, not least the lovely, romantic playing of the violins at around 7:00. However, the warmth always stays on the right side of indulgence. The beautiful slow movement is warmly lyrical at the outset and the BBC musicians offer their distinguished guest some dedicated playing. When the great climax arrives (17:18) the timpanist is superbly incisive – but is his playing also a bit too dominant? I have to say I felt a bit cheated at this point. The climax is over almost in a flash, it seems. The last thing one wants here is grandiosity but the passage should be like a momentary glimpse of heaven and I feel Sanderling’s approach to it is a bit matter of fact and misses the radiance of the moment. The finale features Dame Felicity Lott, who also appeared on Franz Welser-Möst’s EMI recording, a version that I’ve not heard. She sings nicely and Sanderling supports her well, bringing out also the slightly gothic elements in the orchestral passages between the soloist’s verses. But the concluding stanza (from 5:11 onwards) is a bit of a disappointment. The playing isn’t sufficiently hushed, nor is Dame Felicity’s singing. I miss the sense of magical repose that one gets, for example, with Judith Raskin and George Szell or from the luminous Lucia Popp with Klaus Tennstedt. I suppose, perhaps that these last few minutes sum up what, to me, is lacking in this reading, namely innocence and poetry. This is a reading that has many virtues – how could it not with a thoughtful musician such as Sanderling at the helm? Others may respond to it more positively than I have so far but right now it doesn’t feel like a recording to rank beside the very best available versions of the symphony and I don’t believe it’s quite as important an addition to the Mahler discography as was Sanderling’s view of the Ninth. Having said that, I’m not aware that there’s an alternative Sanderling performance of this work available on CD and that in itself makes its appearance worthy of note, especially since Thomas Sanderling says that, after the Ninth, this was the Mahler symphony most frequently conducted by his father. Before the symphony we hear a tautly controlled account of the Don Giovanni Overture. The coupling is apt, for this piece also has both a dark side and a lighter one. Sanderling’s opening is darkly imposing and he leads a muscular account of the main allegro. The playing of the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra is pretty good throughout, with only a few minor rough edges, and brought back for me some happy memories of concert-going in Yorkshire in the years around the time of these recordings. Good, clear BBC studio sound and a useful note complete the attractions of this disc. Though I have some reservations about Sanderling’s reading of the symphony he’s an intelligent and thoughtful Mahlerian and admirers of Mahler or of this conductor should hear this CD. John Quinn