Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

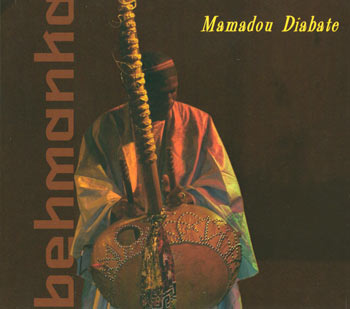

Mamadou Diabate

Behmanka

No other traditional instrument symbolizes the music of the “Mande” cultural region of Western Africa as much as the kora does, the African harp-lute. Its bell-like sound is just as unmistakable as its visual image: a long wooden neck attached to a soundboard made from a large calabash, with a wide bridge anchoring two rows of right-angled strings. The kora proudly symbolizes the richness of African musical traditions. Mamadou Diabate from Mali is a true kora master who bears a last name that comes as an obligation to commit oneself to the music and its traditional importance. Mamadou’s cousin Toumani Diabate is the most famous kora virtuoso of his generation. During the course of his great career, Toumani turned the kora into a powerful solo instrument, playing both melody and accompaniment at the same time. Now Mamadou follows track with an album that exclusively features solo pieces for kora. While the music to be heard on BEHMANKA remains true to the Diabate family tradition, it also is a testament to Mamadou’s individuality as a player and his desire to enrich the purity of the tradition with a contemporary kind of vitality and innovation. The musical result is marked by an atmosphere of great intensity and communicates a magical aura that’s simply irresistable. Just like the other famed kora players of his family, Mamadou Diabate is a jeli (griot). He stands at the end of a long line of professional musicians who have been an integral part of traditional African culture for many centuries. Traditionally, a jeli has been either a court-musician or a minstrel, born into a specific caste. Within the hierarchical structure of African societies, a jeli is a craftsman with special obligations and privileges concerning his relationship towards the upper caste of “nobles” and “freeborn”. For centuries, a jeli mostly worked for a patron who belonged to the aristocracy. He acted as a messenger of important information but was also expected to fashion songs of praise or to embellish social ceremonies with his art. To this day a jeli remains a highly respected figure because of his artistic prowess, even if his social functions have been changed somewhat. Ever since the Malian empire came to an end in the late 15th century and colonialism brought social change to traditional African society, a jeli’s art is also used for illustrating family rituals like weddings or baptisms. He may also work for businessmen or politicians or act as a mediator in a situation of conflict between individuals. A jeli is expected to guard his secret knowledge and be conscious about his special social status. While a great number of songs of praise have been fashioned by jelis in the past, an attitude of deference towards authorities is not desired. He is expected to be a proud man who is aware of his special importance. Moreover, the handing down of legends orally still remains an important part of African culture, with the jeli as a central figure, a moral authority and keeper of traditional social attitudes. He is expected to communicate a sense of history through his music, especially concerning the glories of the Malian empire, a past that stretches back into the 13th century. Traditionally, a jeli’s musical education starts in his own family. He is taught the traditional repertoire of songs and is expected to acquire musical skills. This holds true for Mamadou Diabate as well. He was born in 1975 in Kita, one of Mali’s cultural centers for the Manding people. Mamadou’s father Djelimory Diabate was a great kora player known as N’fa Diabate and a member of the Instrumental Ensemble of Mali. N’fa took part in many of the ensemble’s recordings for Malian National Radio and lived in Bamako where the ensemble was based. When he was just four years old, Mamadou lived with his father for a while, listening to the sound of the kora on a daily basis. It was then Mamadou became aware of the fact that the instrument would be his destiny. As a teenager Mamadou went public as a kora player in his own right, travelling his home region, accompanying singers, playing weddings and baptisms. When he was just fifteen, he won a regional competition and turned into a local celebrity. An apprenticeship in Bamako with his cousin Toumani was next and Mamadou’s ever-increasing performance schedule soon included more and more upscale work. He even acquired a nickname because of his height: “djelika djan” – tall jeli. In 1996, Mamadou Diabate had the chance of joining the Instrumental Ensemble of Mali for a US tour. He decided to stay in the United States and has been doing so ever since, living in Durham/North Carolina with his family. Mamadou has performed in some of the most prestigious institutions ranging from the United Nations to the Smithsonian in Washington DC. He has worked with blues musicians Eric Bibb and Guy Davis, jazzmen Randy Weston and Donald Byrd and folk/pop musicians like Ireland’s Susan McKeown or Angélique Kidjo from Benin. However, his father’s advice of paying special attention to all the great kora players has always remained Mamadou’s special interest. He has acquired a profound knowledge of the tradition and this knowledge is still central to his art today. He may also be an innovator of considerable importance but the Malian “keita” tradition of playing the kora has remained. Mamadou’s present style is marked by a magical combination of depth of spirit, technical brilliance and a tendency towards improvisation. It is for good reason that African folklore includes the legend of kora players being possessed by spirits sometimes, especially when playing at night. It’s a legend somewhat connected to the blues myth, wherein players make a pact with the devil to be able to play the blues. “Tunga”/”Adventure” was the name of Mamadou’s debut album released in 2000. It featured ensemble playing of the highest calibre and included some breathtakingly innovative ideas. While the sound to be heard on BEHMANKA is pure kora, the fusing of various traditions and playing techniques remains. Mamadou Diabate may be a player with one eye on the past and one on the present, but his creative outlook is firmly directed into the future. The music to be heard on BEHMANKA presents a contemporary version of the expressive powers and spiritual depth of African music, performed by a true master musician. BEHMANKA by Mamadou Diabate - solo music for kora on TRADITION & MODERNE. Mamadou Diabate about the music to be heard on “BEHMANKA” 1. Touma Moment. Everything has its moment in time. 2. Jamanadiera I expanded on this traditional song taught to me by my father, N’fa Diabate, and here I play it in my own style. It means both hospitality and beautiful town. 3. Behmanka I grew up listening to my grandfather play Behmanka on the ngoni and my father playing it on kora. It is played by griots to honor Alfa Yaya Jalloh, king of the Futa Jallon region in Guinea. Here I infuse this traditional melody with my creative variations. 4. Koraboloba Big hand of the Kora. The traditional version of this song is called Kuruntu Kelefa, which honors two kings of Gabu, Sanneh and Manneh. Using the original base line as my foundation, I add unique melodies and solos on top. 5. Kita Baro Kita is my birthplace and Baro recalls the communal pastime of coming together, sitting, talking, playing music, dancing, enjoying each other's company. Griots believe that opening the traditional ceremony with this song brings good luck. 6. Jarrabeekele My loved one. When looking for a loved one, men and women should seek someone who is a good match. 7. Sansenefoly Honors the great farmers, celebrates their productivity and their important contribution to society. My father was the first kora player to record „Sansenefoly“ for National Radio in the 1960s and here I kept the traditional style. 8. Djimbaseh Taking creative license, I play this lively dance tune, which was brought to Mali by way of Cassamance, Senegal, and is influenced by Senegal’s trademark dance, Sabar.