Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

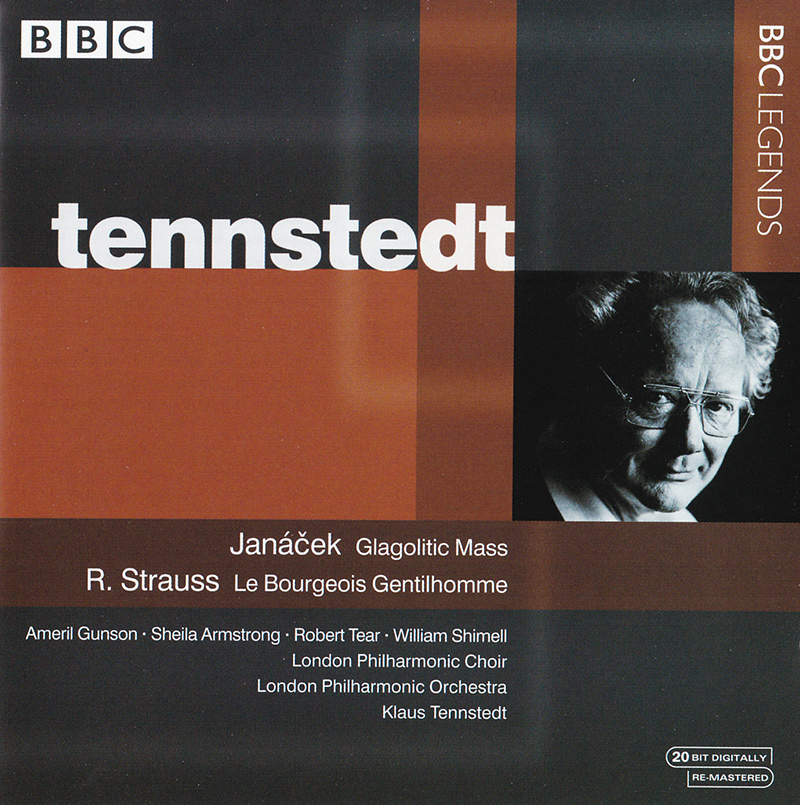

JANACEK, STRAUSS R., London Philharmonic Orchestra, Klaus Tennstedt

Glagolitic Mass / Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, op. 60

- London Philharmonic Orchestra - orchestra

- Klaus Tennstedt - conductor

- JANACEK

- STRAUSS R.

Ever since Klaus Tennstedt’s untimely death in 1998 there has been a steady trickle of live recordings on BBC Legends and the London Philharmonic Orchestra’s own LPO label, not to mention an indispensable EMI DVD of Mahler’s 1st and 8th Symphonies with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and LPO respectively. This latest Legends disc finds Tennstedt and the LPO on less familiar ground, certainly as far as the Janáček is concerned. Perhaps it’s not surprising the results are mixed - to say the least. The Glagolitic Mass had a long gestation. Janáček started work on a mass for chorus and organ as early as 1907-8 but put it aside and returned to it in 1926, using it as the basis for an orchestral mass. He eventually produced a full score but revised it twice, with the result that the 1907-8 contributions were much reduced. Janáček finished the final score at the end of December 1926 and seemed to lose interest in it until May 1927, when the premiere was mooted for December that year. Janáček revised the score yet again and produced a second authorised version but was forced to make changes to suit his provincial players. More unauthorised alterations were made when the score was published after Janáček’s death in 1929. Like most conductors Tennstedt opts for the traditional, revised version of the score, with the opening Úvod rather than the Intrada that begins (and ends) the original one.* The brass blaze out clearly enough here but it is the articulation of this movement that seems to cause the most problems for conductor and players. It is music that can so easily lapse into muddle and bloat – as indeed it does here – and the boxy recording doesn’t help. The descending basses and growling brass at the start of the Kyrie merely confirm the initial impressions of a lack of focus at the bottom end of the spectrum, although at the top the women’s prayerful repetitions of ‘Gospodi pomiluj’ are well caught, as are Sheila Armstrong’s soaring soprano lines. Unfortunately the muffled timpani spoil the music’s more serene closing bars. The surging rhythms of the Gloria need to be much more urgent and better articulated than they are here if the mood of heightened ecstasy is to be achieved. Mezzo Ameral Gunson sings authoritatively enough – she sings the part on Sir Simon Rattle’s earlier CBSO recording for EMI – while tenor Robert Tear sounds suitably transported in his solo, punctuated as it is by some febrile singing from the choir. The cascading ‘Amens’ are well done though, caught between a halo of brass and the low thunder of the organ. This is Janáček at his most transported; thrilling stuff. The Credo has some splendid contributions from soloists and choir, though the ripple of harps barely registers. Here one really needs more transparency if the many felicities of Janáček’s spiky orchestration are to be heard. Don’t forget this is the central movement of the work and, in terms of the mass setting itself, the central all-important statement of belief. Janáček creates a rising spiral of tension but Tennstedt and the LPO really struggle to propel the music forwards and upwards. For their part Tear, Shimell and the chorus do achieve a certain frisson at the close with their transported ‘Amens’, but this just isn’t enough to salvage the movement as a whole. As if this weren’t mountain enough to climb, the opening bars of the gently rocking Sanctus are sabotaged by a distracting cough from the audience. That said the performance has pretty much lost its way by now and despite the heroic efforts of the singers the Sanctus never really gets off the ground. Ditto the Agnus Dei, crowned though it is by some splendidly incisive singing from the chorus. While it is interesting to hear Tennstedt perform something other than Beethoven, Mahler or Wagner, Janáček simply does not play to his strengths; the Strauss most certainly does. Der Bürger als Edelmann is a strange beast. In 1911 Strauss and his librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal decided to combine the composer’s next opera, Ariadne auf Naxos, with spoken theatre based on the text of Molière’s play Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (1670). This ‘preface’, for which Strauss provided the music, didn’t work on the night, so he recast the music as a suite, first performed in 1920. This delightful piece, winningly played by the LPO, finds the composer in neo-classical mode, ripe Romanticism expertly blended with the more formal elegance of courtly dances. This is the Strauss of the late, lyrical operas – Capriccio and Der Rosenkavalier spring to mind – and the warm, expansive recording certainly suits the score. Tennstedt’s affection for this music is evident from the outset with an effervescent Ouverture, nicely articulated and recorded with all the transparency and colour so lacking in the Janáček. The music positively glows, with some glorious tunes for the brass. The two minuets and the courante are nicely sprung and played with a judicious mix of grace and gravitas, while the Fencing Master is portrayed with self-important swagger. The Dance of the Tailors has a more festive air and some delectable horn playing to boot but as the suite progresses it becomes all too obvious why the conceit failed in the theatre; this is just too substantial an hors d’œuvre, given that the main course, Ariadne, has still to follow. If you must hear Tennstedt, warts and all, this issue is self-recommending, but if you want a more cogent and thrilling performance of the Glagolitic Mass you must look elsewhere. Rattle’s much-lauded CBSO account is well worth hearing, notably for its rich, sumptuous recording (EMI Great Recordings of the Century 5669802). For something altogether more astringent, more authentically Slavonic, go for Karel Ančerl and the Czech Philharmonic. The recording dates from 1964 so the sound is typically coarse but this just adds to the raw excitement of the performance (Karel Ančerl Gold Edition, Volume 7, Supraphon SU36672). Both conductors use the revised version of the score so if you want Janáček’s original thoughts you will need to investigate Sir Charles Mackerras’s Danish National Radio recording (Chandos CHAN9310). Unfortunately it is a curiously lacklustre performance that really doesn’t show the original score to its best advantage. For that you will need to invest in the 1996 DVD of Sir Charles and the Czech Philharmonic in blazing form, combining the mass with excellent accounts of Jealousy and Taras Bulba (Supraphon SU70099). The notes themselves are rather basic and not that legible. As most of us don’t have 20/20 vision any more it would really help if recording companies tried a little harder when it comes to choice and size of font for their booklets. Chandos and MDG do a much better job in this respect, so it can be done. The Janáček is hardly an indispensable addition to Tennstedt’s recorded legacy but the Strauss is as genial and elegant a reading as you are likely to find. It is certainly the more successful item on this disc but neither work shows Tennstedt at his considerable best. Dan Morgan Note Paul Wingfield’s excellent book on the genesis of the mass and his reconstruction of the ‘ideal’ version of the score is mandatory reading for all Janáček enthusiasts. Janáček: Glagolitic Mass, Cambridge Music Handbooks, Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0 521 38901 1.