Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

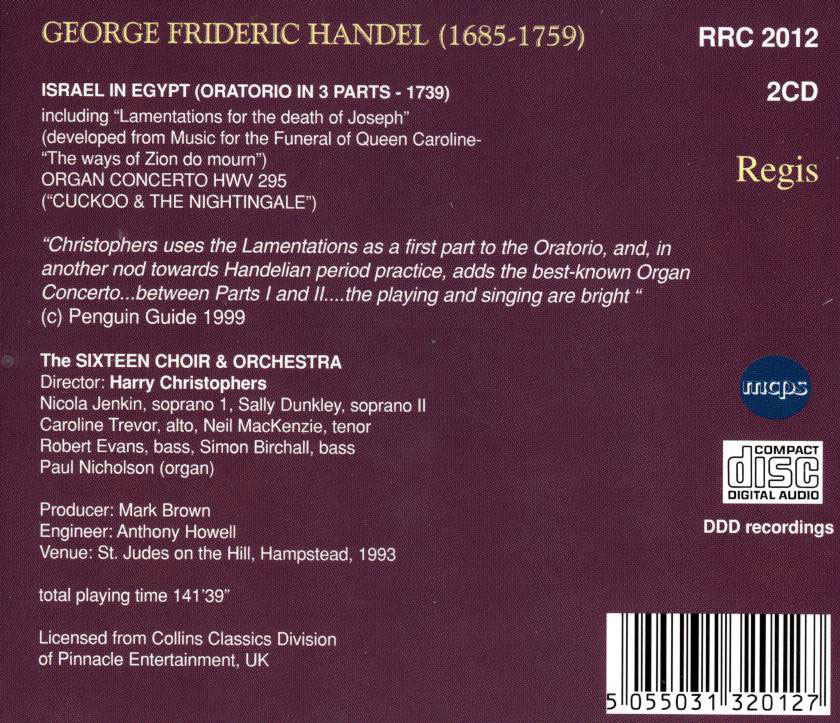

HANDEL, Nicola Jenkin, Caroline Trevor, The Sixteen, Harry Christophers

Israel in Egypt / Organ Concerto HWV 295

- CD.1(74'03")

- ISRAEL IN EGYPT: PART ONE

- "Lamentations for the death of Joseph"

- 1. Largo assai 2.13

- 2. The sons of Israel do mourn 6.35

- 3. He put on righteousness 2.16

- 4. When the ear heard him 3.08

- 5. How is the mighty fall'n 0.49

- 6. He deliver'd the poor that cried 5.41

- 7. How is the mighty fall'n! 0.53

- 8. The righteous shall be had in everlasting remembrance 3.45

- 9. Their bodies are buried in peace 5.39

- 10. The people will tell of their wisdom 2.01

- 11. They shall receive a glorious Kingdom 3.34

- 12. The merciful goodness of the Lord 3.47

- ORGAN CONCERTO in F (HWV 295)

- 13. I.Largo 2.16

- 14. II.Allegro 3.15

- 15. Adagio (ad libatum) 1.34

- Nicola Jenkin - soprano

- Caroline Trevor - alto

- The Sixteen - orchestra

- Harry Christophers - conductor

- HANDEL

"in another nod towards Handelian period performance, adds the best known organ concerto the playing and singing are bright" (Penguin Guide) Israel in Egypt (first named Song of Moses) was composed in October 1738 when Handel was 53 years old. It was calculated to appeal to both Christians and Jews as Handel expected that Christians would find it a suitable subject for Lent, whilst the sizable Jewish community in London would see it as being especially suited to Passover. The 1738 - 39 season saw the premieres of not only Israel in Egypt but also of two other new large scale works by Handel (Saul and a self-composed pastiche Jupiter in Argos). Unfortunately, the audience was rather more attuned to opera than oratorio and expected that Israel in Egypt would contain more solo singing - only four solos and almost forty choruses was not their idea of an exciting evening! At the second performance Handel substituted some songs for the slower moving choruses as well as cutting down on the work's length. There was however sufficient interest in the new work to run to a third performance. Handel though counted the work as one of his failures but blamed the audiences of the day for its lack of success: following a revival in 1756 he wrote that the oratorio `did not take, it is too solemn for common ears'. Israel in Egypt is a choral oratorio. Most of the interest lies in the choral portions of the work and the chorus provides the narrative. Into the piece Handel inserted an already existing choral anthem The Ways of Zion do Mourn, written for the death of Queen Caroline the previous December that, being of a sombre nature, had to be balanced later on by something more lighthearted. The work then became the story of the liberation of the Israelites from captivity in Egypt (the aforementioned funeral anthem for Queen Caroline being retitled Lamentations of the Israelites for the death of Joseph). Part Two dealt with the crossing of the Red Sea and the final part represented the rejoicing of the Israelites at the end of their ordeal. Despite the preponderance of choruses there is much to enjoy in Israel in Egypt. Many of these choruses and dramatic recitatives are compact, and the scoring and harmonies, particularly in the passages describing the various plagues, are highly original and imaginative. Indeed, a vivid imagination must have been almost obligatory in order to set a text which includes such lines as: `And with the blast of thy nostrils the waters were gathered together'; `The floods stood upright as a heap and the depths were congealed in the heart of the sea'; `they sank into the bottom as a stone'; `they shall be as still as stone till thy people pass over'; and `the horse and his rider hath he thrown into the sea'. Handel's orchestral effects in the passages surrounding the plagues of frogs, hailstones and flies also show a lively sense of humour. Perhaps the most vivid item is the short chorus `He sent a thick darkness over all the land, even darkness which might be felt' which Leichentritt in his essay Handel's Harmonic Art has asserted provides a link between Monteverdi and Wagner. Attempts at successfully staging this work have met with mixed fortune: the future Queen Victoria witnessed a performance at Covent Garden of The Israelites in Egypt which turned out to be basically Rossini's Mose with choruses selected from the Handel oratorio. A few months later, in October 1833 Mendelssohn gave a performance of the work with tableaux vivants. It is tempting to speculate upon the staging of the plagues! Mendelssohn wrote in a letter to his sister of his enjoyment of Handel's special effects in the finale: 'Miriam, with a silver timbrel, sounding praises to the Lord, and other maidens with harps and zithers, and in the background four men with trombones, pointing in different directions ... and when the chorus came in forte, real trombones and trumpets, and kettledrums, were brought on the stage and burst in like a thunderclap. Handel evidently intended this effect, for after the commencement he makes them pause till they come in again in C major.' In the 1850s the work was included in the `monster' concerts at Crystal Palace when allegedly some 2000 soloists and 500 instrumentalists took part! Handel, always under some pressure to finish works quickly, was an inveterate borrower, not only of his own works (such as the already mentioned Funeral Anthem for Queen Caroline) but also those of fellow composers. Donald Burrows has drawn attention to an indebtedness to the melodic and harmonic ideas of Alessandro Stradella (1639-1682) and Dionigi Erba, and also to a keyboard canzona by Johann Kaspar Kerll (1627-1693) which Handel used as the basis for his chorus `Egypt was glad when they departed', mainly to provide an intentionally archaic sound. On this recording Harry Christophers has also included another Handel work, the organ concerto known as The Cuckoo and the Nightingale, that was part of a set of concertos published in 1740, and which also borrows from Kerll's "Capricio Cucu". It is not known precisely who provided the libretto (taken from Exodus XV). Some sources maintain that Handel himself adapted the Biblical text, whilst others give credit to Jennens (1700-1773), an Oxford taught literary scholar and editor of Shakespeare who collaborated with Handel in Saul, Belshazzar and The Messiah. It is said that his huge collection of Italian operatic scores were placed at Handel's disposal for his `borrowings'. When Harry Christophers founded The Sixteen in 1977 he intended to perform early English polyphony, works of the Renaissance, and some twentieth century pieces. However when its accompanying orchestra The Symphony of Harmony and Invention, was created, this opened the way to performing and recording some of the glories of the Baroque period such as Handel's Israel in Egypt, Alexander's Feast, Esther and Samson. Accordingly their discography highlights their exploration of and excellence in every era of composition, from an award winning series of English Tudor music and a survey of the Masses of Victoria to works by Martin, Stravinsky, Tavener and Ives. (c) 2000 James Murray, Newquay