Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

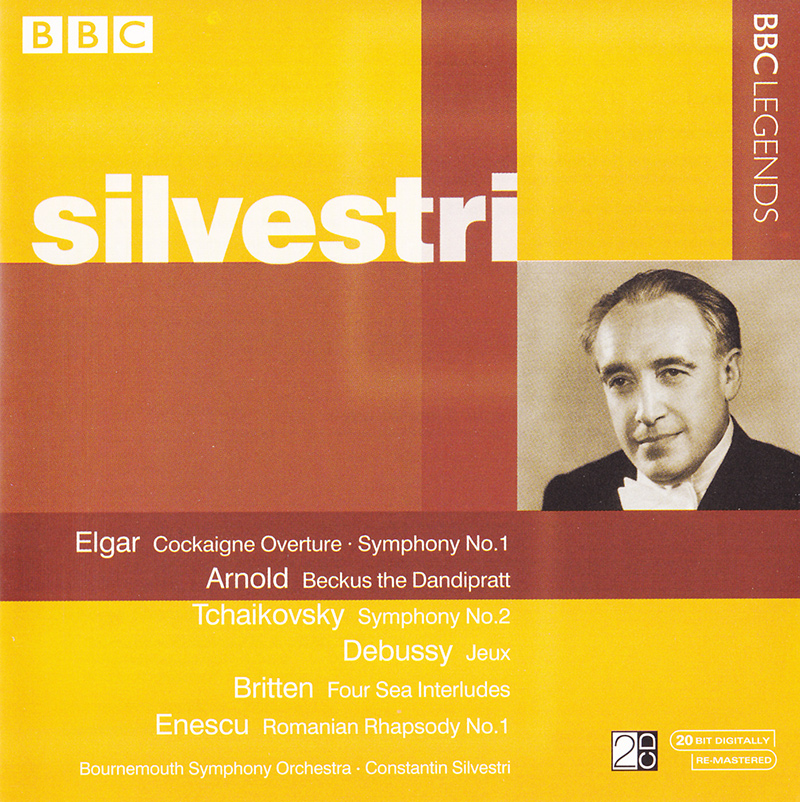

ELGAR, ARNOLD, TCHAIKOVSKY, DEBUSSY, BRITTEN, ENESCU, Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Constantin Silvestri

Cockaigne / Symphony No. 1 in A flat major / Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 17 / Four Sea Interludes

- Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra - orchestra

- Constantin Silvestri - conductor

- ELGAR

- ARNOLD

- TCHAIKOVSKY

- DEBUSSY

- BRITTEN

- ENESCU

During the last year it has been my good fortune to learn more of Constantin Silvestri (1913-1969) as a fully rounded musician, rather than just as a conductor. Performances of his music (review) and reading the only biography of him to appear in English (review) have no doubt been a great help in this, but for many Silvestri remains known exclusively as a conductor of some merit. This second BBC Legends set of Silvestri-led performances is a valuable one because it largely presents works that the maestro never recorded commercially, the exception being Enescu’s First Rhapsody. There were plans to record the Elgar symphonies and even maybe The Dream of Gerontius with the BSO for EMI, but Silvestri died before the sessions could take place. Another point of interest is the provenance of these recordings – each, with the exception of Arnold’s Beckus the Dandipratt overture, was recorded from radio broadcasts by Silvestri himself. His personal recording collection today forms part of the Wessex Film and Sound Archive, now the only available source for these recordings; the original BBC tapes appear to have been lost or deleted. That Silvestri found these performances worth preserving is the point. Whether he intended to use them for pure enjoyment’s sake or as private reference for future recordings, noting from them what worked well or not so well, is not known. Silvestri’s EMI recording of Elgar’s In the South has long held the interest of collectors and alerted listeners to the conductor’s credentials. His conception of Elgar to my ears is somewhat more hot-blooded than you get with, say, Adrian Boult. That does not suggest however that Silvestri cannot be just as persuasive. His Cockaigne overture (In London Town) is drawn across a fairly large canvas with bold gestures. You feel that this is perhaps not a native Londoner’s account, but Silvestri swaggers with confidence and affection along the city streets as he takes the BSO through the score. Elgar has never seemed to me the most natural of symphonists. Indeed, it is worth noting that Elgar himself took time to come to terms with his compositions in the genre. That Silvestri largely makes sense of the work and convinces me that Elgar is an impressive symphonist is much to his credit. The work doesn’t adopt the notion of contrasting ideas throughout its duration, but presents this idea in contrast with the slow evolution of phrasing from a germinal idea. Silvestri launches the opening movement by adopting a broad tempo that amply brought out the ‘nobilmente’ inherent in scoring and directive marking. The BSO plays with surging tone that carries a strong sweep to the line, and even slow-building premonition at times. That the orchestra has been well drilled is evident, with clarity of individual lines being important for Silvestri. He is not afraid to shade down more than other conductors (notably Boult) at times but the playing he secures falls squarely within the natural Elgarian tradition. The second movement is taken at a brisk striding pace with the brass and timpani coming well to the fore when required. Real enjoyment is captured in the music-making. The third movement is notable for the BSO’s luxuriant string tone and delicately spun wind lines – a fine testament to the level of playing Silvestri brought the BSO to during his tenure. The closing movement has a grandeur about it that still further bespeaks confidence in the playing, moving from passages tinged with shadows and half-lights recalling the opening movement towards a conclusion that carried forward by its own inevitability. Malcolm Arnold’s wonderfully titled Beckus the Dandipratt overture can easily be thought to be an English cousin of Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel. There’s certainly fun to be had here and Silvestri – a man of keen wit himself – leaves no joke untold. That the idiom of the piece seems resolutely to straddle the idioms of both English and continental Romanticism at times surely helps Silvestri’s cause. Just as in rehearsals he would flit between languages to get his point across, so it is with the music here. Who’s to mind if it’s a strange mix; it works wonderfully and one can sense the BSO’s enjoyment of the high jinx too. The LPO are about to release a recent live account of this overture under the direction of Vernon Handley. I’m willing to bet that it’s a close run thing between the two accounts; with stereo sound of some immediacy adding to the attractiveness of Silvestri’s account; this is a version that will take some beating. For me the high point of the set is found at the start of the second disc: Tchaikovsky’s Second Symphony. With the first and the third symphonies, or the latter two piano concertos, it has been long overlooked by the public, orchestras, conductors and music promoters. Silvestri makes a serious and cogent case for its place in the mainstream repertoire of any self-respecting orchestra. Unafraid to demand bold, though never harsh, playing from the BSO, Silvestri draws out the drama of the work in the grandest of gestures. The opening Andante sostenuto is immediately meditative in character, before contrasting with a rather livelier Allegro vivo second section. With his instinct for dramatic contrast, Silvestri makes much of the movement through investing it with strong rhythmic incisiveness whilst never neglecting sonority of brass parts in particular. The march rhythms evident within the second movement rise and fall in prominence throughout is span to create gentle contrasts with more lyric material. The brisk scherzo and trio third movement showcases some lively upbeat playing across all orchestral sections, often with delicacy being at the forefront of considerations. Silvestri however ensures that contrasting emotions are present as he builds the influence of certain and imposing passages. The final movement picks up on this notion with grandly phrased brass and timpani opening flourishes, before moving on to efficiently contrast three distinct sections and secure a powerful conclusion. Listen to how the piccolo line bounces jauntily along briefly to provide colour against the massed strings and percussion. Indeed, with all Silvestri’s undoubted affinity for the showy elements of music-making, there is much material here that suits his particular style of music-making. The BSO are more than willing to follow his lead. This is a reading I will revisit with much enthusiasm for the contributions of all concerned. As in the Elgar symphony, the sound quality is very clear. Climaxes are full and uncongested, with piano lines being well captured too. Debussy’s Jeux comes from an entirely different sound world, but one that Silvestri had some experience of as head of the Paris orchestra after leaving Bucharest. The quality of the sound does much to disrupt Silvestri’s game of tennis with Debussy, so much so that it seems one game short of being a full set played. With so much of the score reliant upon spatial clarity and the vivid interplay of voices it’s a shame that the somewhat congested acoustic does not let something more representative of Silvestri’s full interpretation to come through. Another mixed success is the recording of Britten’s Four Sea Interludes from Peter Grimes which is marred by significant audience coughing in places. Enescu might have grown to particularly resent that his youthful first rhapsody overshadowed more intricate and representative compositions, but Silvestri made it his calling card encore of choice around the concert halls of the world. Standing in the wings he would give a signal for the wind soloists to begin the freely spun opening, prior to Silvestri timing his arrival at the podium to bring in the first orchestral tutti. A clap-trap, sure, but then perhaps only a showy and mercurial genius such as Silvestri could pull it off with fresh abandon time after time. This account certainly makes his Vienna Philharmonic studio recording seem a touch lacking in willingness to push things to extremes. Underneath it all though is a feeling for the music and a joy in making it that is never in doubt alongside such evident affection for his homeland. Silvestri’s reputation as a serious and colourful maestro is well served by these vividly characterised performances: this 2 CD set is most enthusiastically recommended. Evan Dickerson