Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

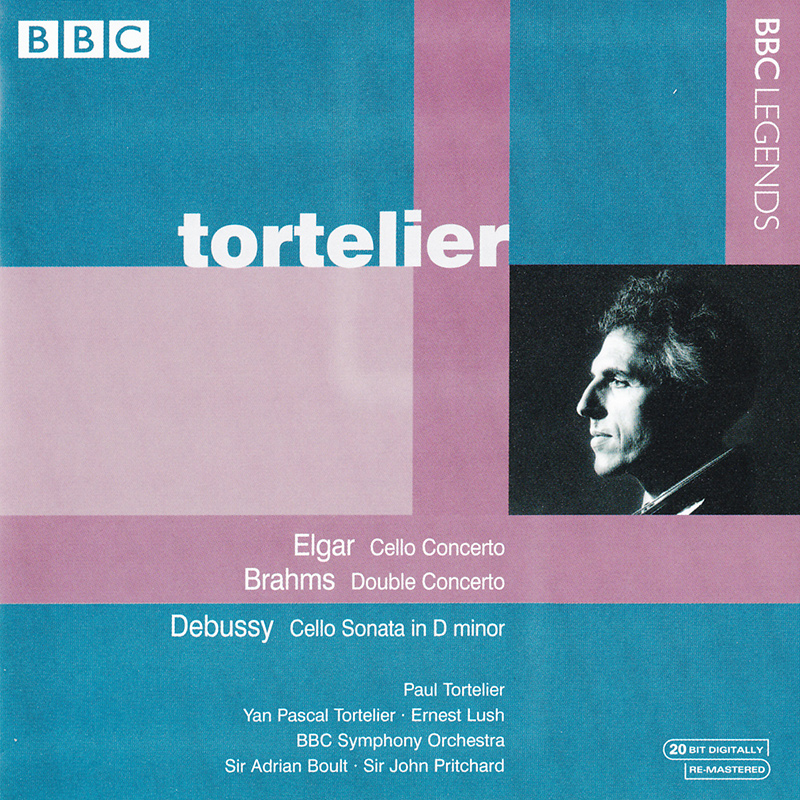

ELGAR, BRAHMS, DEBUSSY, Paul Tortelier, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Sir Adrian Boult, John Pritchard

Cello Concerto in E Minor, Op. 85 / Double Concerto in A Minor, Op. 102 / Cello Sonata in D Minor

- Paul Tortelier - cello

- BBC Symphony Orchestra - orchestra

- Sir Adrian Boult - conductor

- John Pritchard - conductor

- ELGAR

- BRAHMS

- DEBUSSY

I had the distinct pleasure of seeing and hearing cellist Paul Tortelier (1914-1990) perform the Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations at Carnegie Hall in the late 1980s, and I recall vividly his peerless tone and smooth style, and that mane of white lion’s hair he touted and threw back with such gusto, much as Stokowski had paraded his famous hands in profile. The BBC archives give us three discreet concerts, of which the Elgar Cello Concerto (14 November 1972) with Boult at the Royal Festival Hall proceeds with sizzling acuity, especially as Tortelier made a point of playing Elgar’s 9/8 main theme without any emotional slides or added note values. Tortelier’s large hand facilitates the sautille passagework of the Scherzo with discernible ease, so it becomes a blistering etude that calls for the bow to touch the string lightly and in constant motion. Tortelier chose to record the Elgar Concerto three times, once with Sir Adrian Boult, although my personal favorite remains that with Sir Charles Groves. It is to this last inscription that this performance owes a strong similitude, especially in the depths to which Tortelier plumbs the Adagio. Tortelier’s high singing line bursts into a jaunty song, almost a kind of hornpipe, which prefers to wax lyrical rather than frolic in ribaldry. The light, quick passages Boult tosses off with his own sense of flair, the brass figures blazing so as to maintain Sir Adrian’s repute as “the British Toscanini.” The extended meditations and accompanied recitatives prove quite hearty, Tortelier often underlining the phrases with an extra pressure on the cello strings, colored by a fast vibrato. The finale, a hail of musical bullets, sets off the audience in a frenzy of applause. Tortelier claimed that it was Serge Koussevitzky who taught him the Brahms style; here (17 April 1974), with Sir John Pritchard at the Royal Festival Hall, Tortelier joins his son Yan Pascal for a deliberate, studied rendition of the Double Concerto, a work Paul Tortelier had inscribed with Christian Ferras and conductor Paul Kletzki. Pritchard rouses the orchestra’s circulation for the first of the big tuttis, the gestures sweeping and lofty. Both a massive tour de force and an intimate chamber piece, the A Minor Concerto asks each soloist to weave his part into discreet sound groups, concertante with strings or among the winds and horns. Yan Pascal Tortelier packs a thin, nasal sound, the violin often projecting an oboe sonority. Some gorgeous harmonies from the brass section before the last big chords of the first movement coda. A suave Andante, eminently songful, with guided plaints from the French horn, flute, and clarinet in colloquy with the two string soli. The concluding Vivace movement several times assumes a Gallic transparency, although the tympani part asserts itself vigorously. The interior voices almost subsume the main thematic elements in the course of the development, with only the ritonello’s saving us from the contrapuntal mix. The last pages enjoy the blending of soli, flute, and French horn in elegant harmony, the Torteliers’ string tone persuasively sonorous to the final chords. The Debussy Sonata (10 February 1959) is a studio performance that complements Tortelier’s troubadour persona with the keyboard virtuosity of Ernest Lush, known for his work with contralto Marian Anderson. Each of Debussy’s movements exploits a different character of the cello, from high tessitura to col legno and pizzicati, to extended melodies and guitar effects. Tortelier makes sweet work of it all, with Lush a velvet glove at every turn. (One caveat: my copy had a cut in the opening chord of the Brahms, and the Brahms Andante‘s first chord was the piano chord that opens the Debussy Sonata.) –Gary Lemco