Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

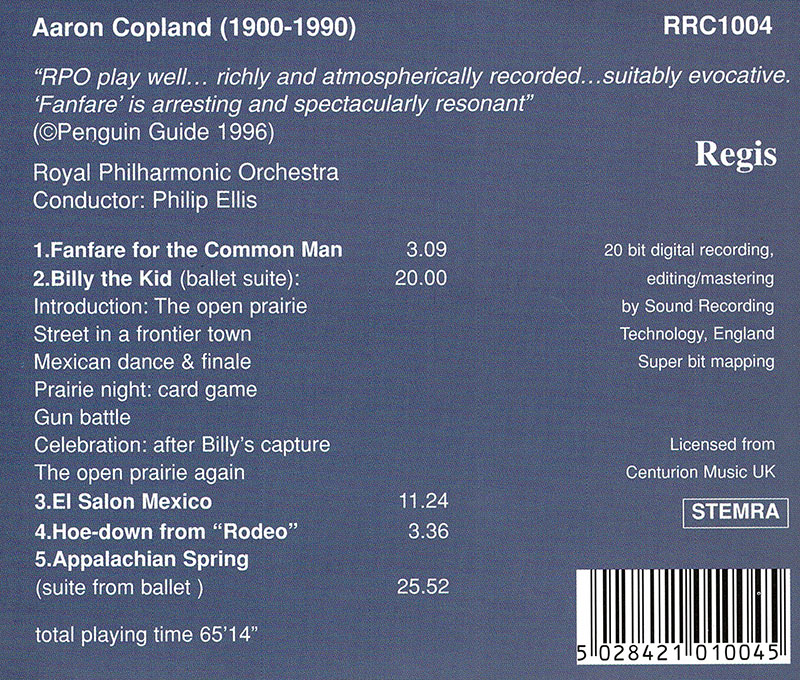

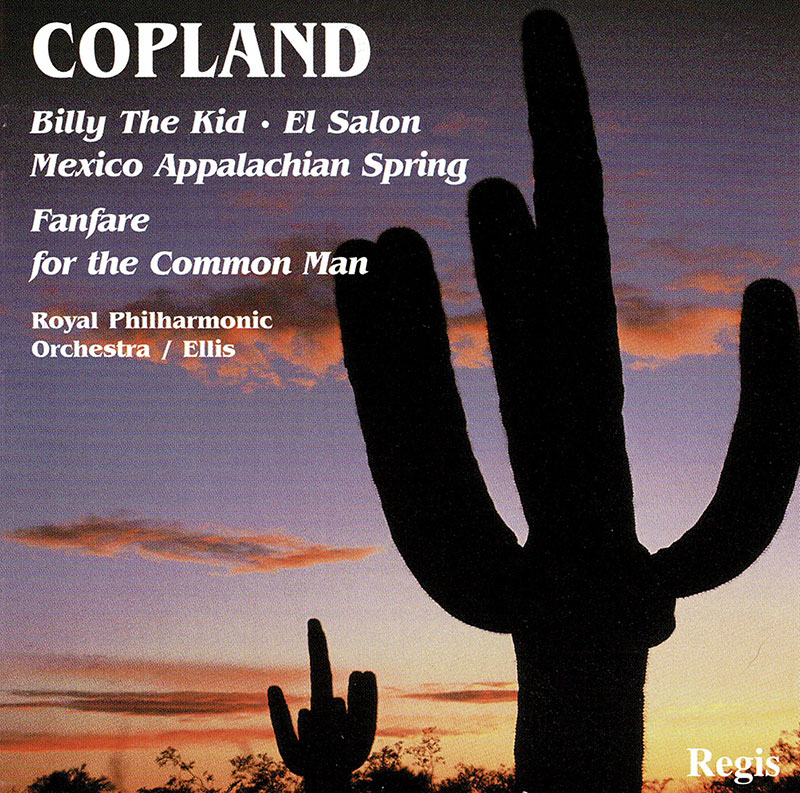

COPLAND, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Philip Ellis

Appalachian Spring

- 1.Fanfare for the Common Man 3.09

- 2.Billy the Kid (suite from ballet): 20.00

- Introduction: The open prairie

- Street in a frontier town

- Mexican dance & finale

- Prairie night: Card game

- Gun battle

- Celebration: after Billy's capture

- Open prairie again

- 3. El Salon Mexico 11.24

- 4. Hoe-down from "Rodeo" 3.36

- 5. Appalachian Spring (ballet suite) 25.52

- total playing time 65'14"

- Royal Philharmonic Orchestra - orchestra

- Philip Ellis - conductor

- COPLAND

The Great Depression ushered in a change in American classical music. Whilst hitherto American composers had either looked to Europe for inspiration or had had to appeal to the perceived sophistication of the city dwellers the dreadful plight of rural communities in the 1930s which was recorded on newsreel and in documentary film inspired composers to depict rural life in all its rawness. Several pioneering film scores from this period have outlasted their films such as those written by Virgil Thomson The plough that broke the plains (1936) and The River (1937). Later, during World War Two the larger studios were fired with patriotic fervour and reminded the folks back home of what they owed to small-town America, either by portraying the ordinary man as hero or by looking back through rose-tinted glasses to its Currier and Ives-like past. Post-war society as part of its rebuilding then became fixated with new convenient technology and suddenly the old rural values were cast aside just as American music which had been for a while dominated by the rugged wide open spaces became more impersonal. This attractive and dynamic selection of music by Aaron Copland (1900 - 1990) dates from the Depression and World War Two era, when, in collaboration with some of the then greatest figures in the world of dance such as Martha Graham and Agnes de Mille, Copland created such all-American classics as Appalachian Spring and Rodeo. His early career had seen him studying in Paris with Nadia Boulanger from 1921 and coming under the influence of jazz (as Symphony no. 1, Music for Theater and the Piano Concerto demonstrate). However, increasingly brittle and terse mannerisms crept in marking his works up to about 1933 (such as the Piano Variations and the Short Symphony which on first hearing resemble something between Stravinsky and Schoenberg). He then broke away from this form of musical modernism, changing direction with pieces inspired by Latin American and American folk dance. Not only were these works easy on the ear but were often designed for relative ease of performance much like the Gebrauchmusik such as was being fashioned by Hindemith or Orff in Europe at this time. The opening piece on this compilation Fanfare for the Common Man (1942) was Copland's contribution to several commissions meted out to a number of American composers by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra to introduce concert programmes during that particular season. This being the darkest period of the war for the Allies, something patriotic and uplifting was clearly expected and Fanfare fitted the bill! The 1938 ballet Billy the Kid employed actual American folk material in the form of the cowboy song "Goodbye Old Paint" set to an irregular beat to give a wonderfully lop-sided effect. Alongside the intended humour are some highly expressive passages that serve to intensify the pathos of this work portraying the life and death of one of America's most renowned outlaws. For El Salon Mexico (1933 - 36) we move joyfully south of the border, the work's title referring to a dance hall in Mexico City. Copland first visited Mexico in 1932 and noted at the time many typical Latin dance rhythms that later became absorbed into this piece. The next extract takes us back into the wide open spaces for the Hoe-Down from Rodeo, first performed at the Metropolitan Opera New York by the Ballet Russes de Monte-Carlo in 1942. This track forms the last part of an orchestral suite of the ballet. This selection of Copland finishes with his suite from the ballet Appalachian Spring (1944), depicting events surrounding a wedding in the Pennsylvanian farming community. From its slow opening the piece progesses through a love scene between the bride and her fiance, a revivalist prayer meeting, to the wedding itself when we hear variations on the familiar Shaker hymn "The Gift to be Simple" before the celebrations die down to a quiet and peaceful coda. Perhaps it is this work that most fully encapsulates Copland's style at this period - direct, unassuming, sincere but certainly not lacking in humour. His music seems to go hand in hand with the work of the great photographer Norman Rockwell, who made such memorable studies of everyday life in rural America. This richly original middle period came to a close with his Symphony no 3 (1946). Other works dating from this fecund period include the film scores for Of Mice and Men (1939) and Our Town (1940). A work that has worn less well is Lincoln Portrait (1942) - its text seems less relevant now than in the dark days of World War Two. Thereafter his style changed quite radically when he appeared to be embracing the twelve-tone system, but somehow he never seemed comfortable within its confines. Certainly these later works have never caught the public's imagination as did the great works of the 1930s and 1940s. Occasionally he attempted to return to that `open air' style as in his opera The Tender Land (1954), a mid-west drama set during the Depression but generally speaking, further successes proved few and far between. ©James Murray 2000 Review: "richly and atmospherically recorded" "Fanfare is arresting and spectacularly resonant" (Penguin Guide)