Logowanie

Dziś nikt już tak genialnie nie jazzuje!

Bobby Hutcherson, Joe Sample

San Francisco

SHM-CD/SACD - NOWY FORMAT - DŻWIĘK TAK CZYSTY, JAK Z CZASU WIELKIEGO WYBUCHU!

Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Elvin Jones

Speak no evil

UHQCD - dotknij Oryginału - MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

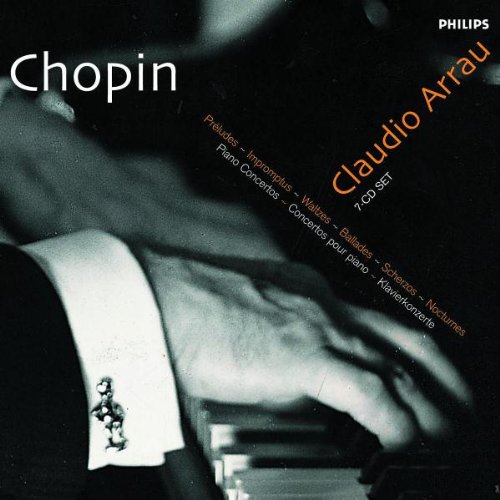

CHOPIN, Claudio Arrau, Eliahu Inbal, The London Symphony Orchestra

Chopin

- Claudio Arrau - piano

- Eliahu Inbal - conductor

- The London Symphony Orchestra - orchestra

- CHOPIN

Although Claudio Arrau (190391) was unquestionably among the greatest pianists of the 20th century (for one writer‚ ‘like God teaching Adam on Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel roof; liquid‚ mysterious‚ profound‚ alive’‚ for another ‘like Atlas holding aloft the universe’)‚ his epic view of Chopin‚ his way of leaving no stone unturned in his quest for poetic truth and gold‚ has always provoked controversy. ‘Giving blood’ (Arrau’s words) can have its downside in a composer who so elegantly and resolutely reconciled slavic passion with gallic nonchalance. Heard live‚ Arrau could exhaust and overwhelm his listeners with the towering rhetoric and intensity of his interpretations‚ but his later recordings in particular (Philips 7CD box is of performances dating from 197080) can prompt both awe and resistance. A diplomat in appearance‚ Arrau could be sharply critical (Rachmaninov – both as composer and pianist – Gieseking and Bolet were among his targets) and consequently he invited criticism in return. More positively‚ Arrau gives us a Fantasie combining fire with his more characteristic breadth and nobility. From him the music’s dark and welling undertow breaks out into a dazzling and heroic radiance. His eloquence‚ too‚ in the concertos‚ where he is superbly partnered‚ is formidable. He may put years on Chopin’s early ardour yet he makes it hard to resist such ripeness‚ such speaking eloquence. And if there are times‚ notably in the F minor Concerto‚ when one longs for a less overbearing manner‚ for a more natural grace and impetus‚ the riches are still infinite. I have already written about Arrau’s tortured but mesmeric dissection of the Nocturnes‚ a quality that invades the more urbane world of the Waltzes to a damaging degree. Here sentiment degenerates into sentimentality and if there are successes in the more inward numbers (Nos 3 and 7) where Chopin is lost in bittersweet reflection‚ there is so much rhetorical panting and puffing elsewhere that one ends wishing he would leave well alone. For the most part he gives us stiffjointed‚ flatfooted dancers quite without the patrician ease and grace of a Rubinstein or Lipatti. Lovers of brio and volatility (always central to Chopin’s storytelling) will note sluggish reflexes in both the Ballades and Scherzos (try the lilting principle subject of the Third Ballade‚ the central più lento from the First Scherzo or an impossibly bloated view of the Fourth Scherzo’s mercurial grace)‚ and despite intermittent triumphs it is difficult to reconcile Arrau’s powerful idiosyncrasy with Chopin’s directions in the 24 Preludes. Why such a detached view of the composer’s morbidity in No 2‚ why so plodding and literal in No 17‚ why such a taming of the furies at the start of No 24? The Philips transfers are admirable‚ and devotees for whom Arrau could do no wrong will have to have this box. But newcomers should be warned that Arrau’s Chopin is heavily teutonic (though born in Chile he was trained in Germany) with only fleeting glimpses of his earlier flexible and lighter genius.