Logowanie

Weekend z Julie LONDON

FUNDAMENTY jazz-kolekcji

Lou Donaldson, Herman Foster, 'Peck' Morrison, Dave Bailey, Ray Barretto

Blues Walk

85 lecie BaLUE NOTE - ceny jubileuszowe

Art Taylor, Dave Burns, Stanley Turrentine, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers

A.T.'s Delight

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Stanley Turrentine, Grant Green, Horace Parlan, Ben Tucker, Al Harewood

Up At Minton's

JEDNA Z 25 NAJLEPSZYCH PŁYT Z KATALOGU BLUE NOTE

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

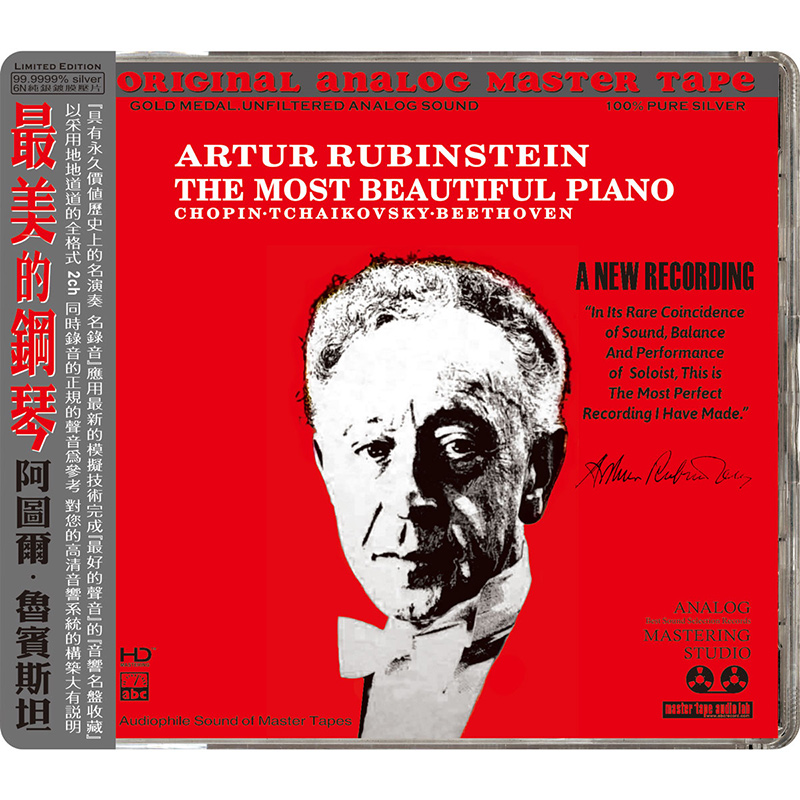

CHOPIN, TCHAIKOVSKY, BEETHOVEN, Arthur Rubinstein

Arthur Rubinstein - The Most Beautiful Piano

- Arthur Rubinstein - piano

- CHOPIN

- TCHAIKOVSKY

- BEETHOVEN

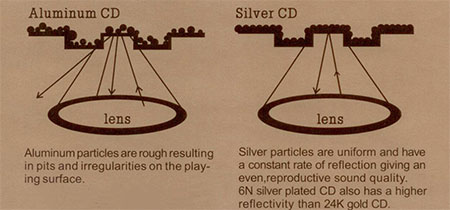

ULTRA Analog CD - AAD is a Digital Copy Of The Master Tape - SILVER CD

Cząsteczki srebra są jednolite i mają stały współczynnik odbicia, co zapewnia równą, reprodukcyjną jakość dźwięku. Posrebrzany `CD 6N ma również wyższy współczynnik odbicia niż 24-karatowe złoto.

“On stage, I will take a chance. There has to be an element of daring in great music-making. These younger ones, they are too cautious. They take the music out of their pockets instead of their hearts.”

Born in Lodz, Poland, in 1887, Arthur Rubinstein became one of the great pianists of the twentieth century. At age three, Rubinstein began to study piano, and within five years he had given his first public performance. When Rubinstein was ten, his mother took him to audition for the famous violinist, Joseph Joachim. Impressed by the young boy’s performance of Mozart, Joachim agreed to be responsible for his general and musical education. Leaving her son to study in Berlin, Rubinstein’s mother returned to Lodz. He would never return to live with his family.

Joachim, who remained the young Rubinstein’s close advisor, introduced him to Heinrich Barth. It was under Barth’s tutelage that Rubinstein made his first steps toward serious performance. After only three years of study in Germany, Rubinstein made his debut at the Beethoven Saal with the Berlin Philharmonic. He played works by Mozart, Chopin, and Schumann, as well as Camille Saint-Saens’s Concerto no. 2 in G, which he would continue to play throughout his career. Amazed by Rubinstein’s performance, one critic wrote “He played everything, not as a child prodigy, but as a mature, adult musician.”

Rubinstein continued to play throughout Europe to rave reviews. In 1906, he traveled to New York to perform at Carnegie Hall. The reception in New York was cool, but he finished the 75 concert tour of the country as he had planned. After returning to Paris, Rubinstein refrained from public appearances for four years. During this time, he lived a tempestuous existence — at times he was poor and without a place to sleep, and at others he lived among the cultured elite. He continued to practice, however, and became friends with the conductor Serge Koussevitzky and the composer Igor Stravinsky. In 1914, with the beginning of World War I, Rubinstein left Paris for Spain.

Rubinstein’s tour of Spain was a major turning point in his life. He had become a more mature and passionate pianist since his performance at Carnegie Hall and the people of Spain responded to him enthusiastically. While there, he learned Spanish and began to play the works of Spanish composers Manuel de Falla, Isac Albéniz, and Enrique Granados. His playing was not the controlled sedate playing of the traditional classical musician, but a wild unrestrained embrace of the piano. It was his charismatic and passionate playing, rather than his virtuosity, which drew large audiences. Rubinstein followed his visit to Spain with an equally well-received extended tour of South America. These performances gave him the money and encouragement to return to Europe and continue performing.

Once in Paris, he returned to the frenzied life he led before the war. With his friends, Cocteau and Picasso, he enjoyed the social life of the artist, but felt his own playing had come to a standstill. It was not until he was forty that he decided to settle down. It was then that he met the daughter of the great Polish conductor, Emil Mlynarski. Though Nela Mlynarski was nearly twenty years younger than he, they were married in London in 1932. More than anything else, it was this relationship and the beginning of family life that imposed upon Rubinstein a need to return to the rigors of study. Soon after the birth of their first child, Rubinstein rented a small farmhouse and began to practice twelve to sixteen hours a day.

In 1937, Rubinstein returned to Carnegie Hall at the height of his powers. It had been more than thirty years, and this time he was hailed as a genius. In his performance of Chopin, critics saw not only the master musician, but a revolutionary re-interpretation of the composer’s work. Rubinstein realized that the growing threat of Nazi occupation necessitated his family’s immediate relocation to America, where he found a home in Los Angeles among a number of other European refugees. Although he became a citizen in 1946, he lived most of his later life in Europe. After the war and the loss of his entire family in Lodz, he dedicated himself to performing publicly in support of the new state of Israel.

Despite his age and failing health, Rubinstein continued to perform throughout his seventies and eighties. Even after going blind, he traveled the world lecturing and teaching. At the age of eighty-three he finished his biography, MY MANY YEARS, and six years later left his wife for another woman. He died in Geneva, Switzerland in 1982, and his ashes were buried in an Israeli forest named after him. Among his many awards were the French Legion of Honor and the American Medal of Freedom. His life long commitment to music and his extensive body of work remain an inspiration to classical music lovers around the world.

“On stage, I will take a chance. There has to be an element of daring in great music-making. These younger ones, they are too cautious. They take the music out of their pockets instead of their hearts.”

Born in Lodz, Poland, in 1887, Arthur Rubinstein became one of the great pianists of the twentieth century. At age three, Rubinstein began to study piano, and within five years he had given his first public performance. When Rubinstein was ten, his mother took him to audition for the famous violinist, Joseph Joachim. Impressed by the young boy’s performance of Mozart, Joachim agreed to be responsible for his general and musical education. Leaving her son to study in Berlin, Rubinstein’s mother returned to Lodz. He would never return to live with his family.

Joachim, who remained the young Rubinstein’s close advisor, introduced him to Heinrich Barth. It was under Barth’s tutelage that Rubinstein made his first steps toward serious performance. After only three years of study in Germany, Rubinstein made his debut at the Beethoven Saal with the Berlin Philharmonic. He played works by Mozart, Chopin, and Schumann, as well as Camille Saint-Saens’s Concerto no. 2 in G, which he would continue to play throughout his career. Amazed by Rubinstein’s performance, one critic wrote “He played everything, not as a child prodigy, but as a mature, adult musician.”

Rubinstein continued to play throughout Europe to rave reviews. In 1906, he traveled to New York to perform at Carnegie Hall. The reception in New York was cool, but he finished the 75 concert tour of the country as he had planned. After returning to Paris, Rubinstein refrained from public appearances for four years. During this time, he lived a tempestuous existence — at times he was poor and without a place to sleep, and at others he lived among the cultured elite. He continued to practice, however, and became friends with the conductor Serge Koussevitzky and the composer Igor Stravinsky. In 1914, with the beginning of World War I, Rubinstein left Paris for Spain.

Rubinstein’s tour of Spain was a major turning point in his life. He had become a more mature and passionate pianist since his performance at Carnegie Hall and the people of Spain responded to him enthusiastically. While there, he learned Spanish and began to play the works of Spanish composers Manuel de Falla, Isac Albéniz, and Enrique Granados. His playing was not the controlled sedate playing of the traditional classical musician, but a wild unrestrained embrace of the piano. It was his charismatic and passionate playing, rather than his virtuosity, which drew large audiences. Rubinstein followed his visit to Spain with an equally well-received extended tour of South America. These performances gave him the money and encouragement to return to Europe and continue performing.

Once in Paris, he returned to the frenzied life he led before the war. With his friends, Cocteau and Picasso, he enjoyed the social life of the artist, but felt his own playing had come to a standstill. It was not until he was forty that he decided to settle down. It was then that he met the daughter of the great Polish conductor, Emil Mlynarski. Though Nela Mlynarski was nearly twenty years younger than he, they were married in London in 1932. More than anything else, it was this relationship and the beginning of family life that imposed upon Rubinstein a need to return to the rigors of study. Soon after the birth of their first child, Rubinstein rented a small farmhouse and began to practice twelve to sixteen hours a day.

In 1937, Rubinstein returned to Carnegie Hall at the height of his powers. It had been more than thirty years, and this time he was hailed as a genius. In his performance of Chopin, critics saw not only the master musician, but a revolutionary re-interpretation of the composer’s work. Rubinstein realized that the growing threat of Nazi occupation necessitated his family’s immediate relocation to America, where he found a home in Los Angeles among a number of other European refugees. Although he became a citizen in 1946, he lived most of his later life in Europe. After the war and the loss of his entire family in Lodz, he dedicated himself to performing publicly in support of the new state of Israel.

Despite his age and failing health, Rubinstein continued to perform throughout his seventies and eighties. Even after going blind, he traveled the world lecturing and teaching. At the age of eighty-three he finished his biography, MY MANY YEARS, and six years later left his wife for another woman. He died in Geneva, Switzerland in 1982, and his ashes were buried in an Israeli forest named after him. Among his many awards were the French Legion of Honor and the American Medal of Freedom. His life long commitment to music and his extensive body of work remain an inspiration to classical music lovers around the world.