Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

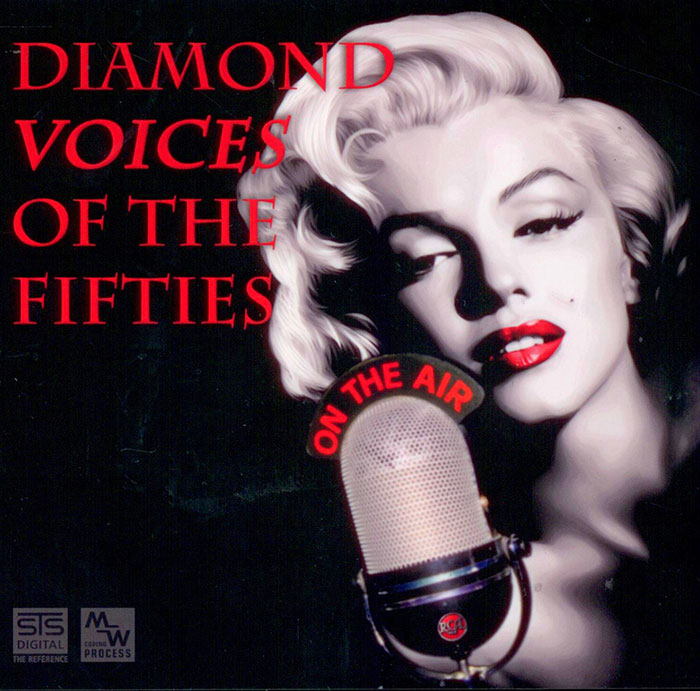

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

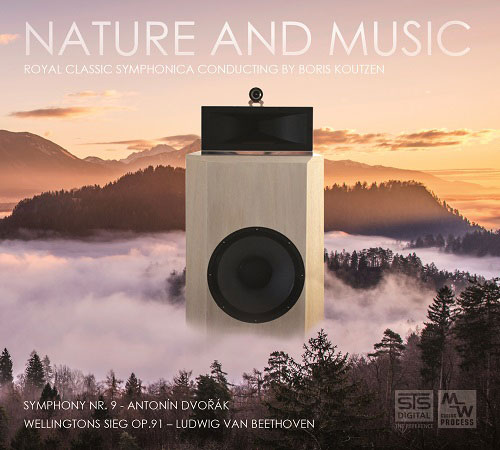

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

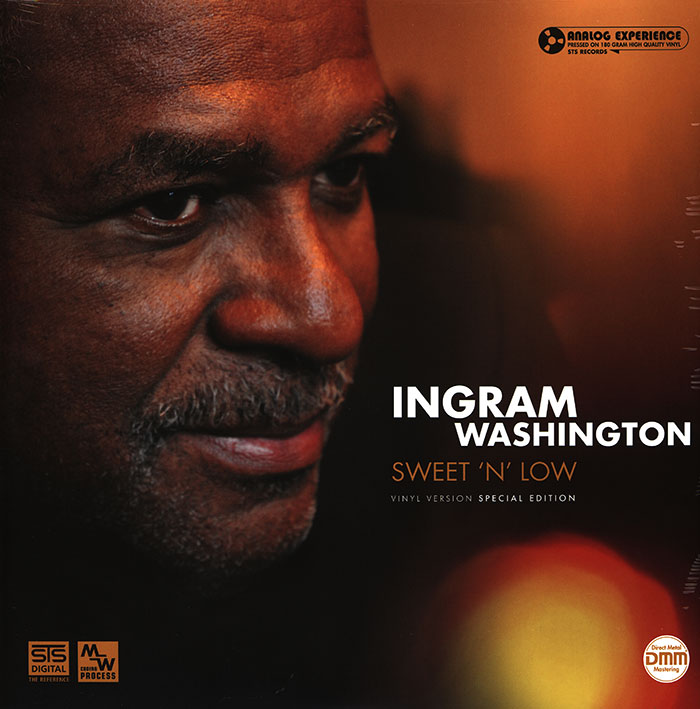

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

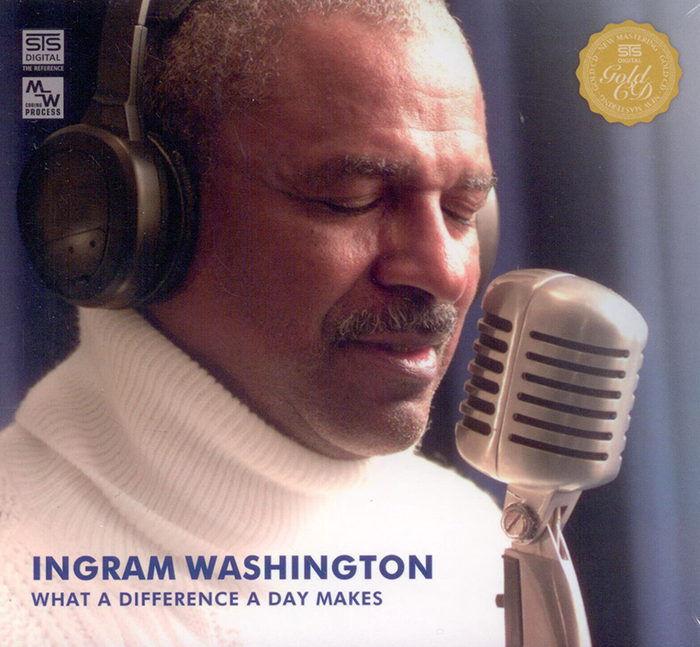

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

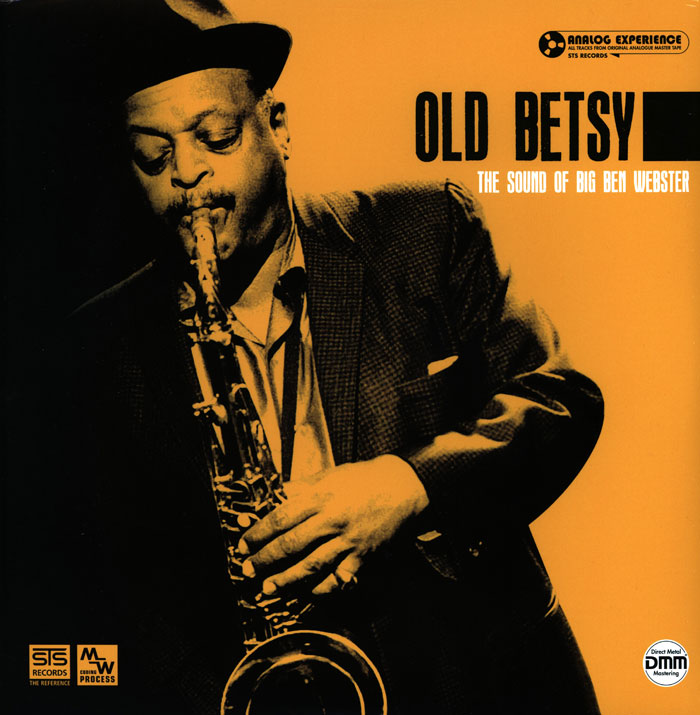

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

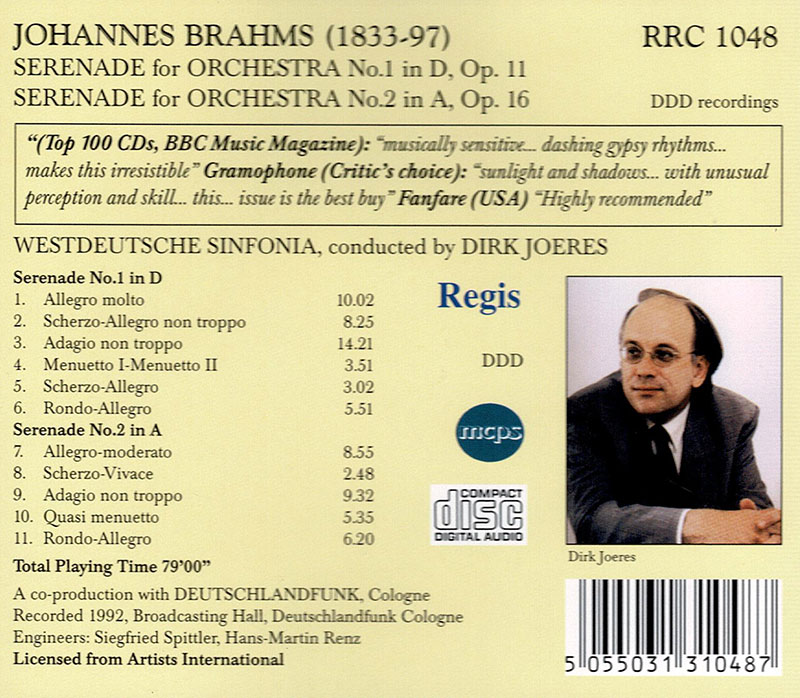

BRAHMS, Westdeutsche Sinfonia, Dirk Joeres

Serenades for Orchestra 1, 2

- Westdeutsche Sinfonia - orchestra

- Dirk Joeres - conductor

- BRAHMS

"musically sensitive... dashing gypsy rhythms... makes this irresistible" (BBC Top 100 CD ) "highly recommended" (Fanfare USA) "best buy" (Gramophone Editors Choice) Johannes Brahms (1833-97) Serenade No.1 in D, Op.11 Serenade No.2 in A, Op.16 Beethoven's genius stood before Brahms like a brilliant but frightening ideal. "I will never compose a symphony", the composer lamented (even as a mature man) to his friend, the violinist Joseph Joachim. "You have no idea what someone like me feels, always hearing this giant marching along behind". This father-figure particularly oppressed the young Brahms, for whom a performance of the Ninth in 1854 became a significant experience. Following this performance, Brahms transformed his symphony into the D Minor Piano Concerto, which was not a success when it was first performed at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1859. Plagued with self-doubt, he conceived and rejected many symphonic ideas; fourteen years lie between his first sketches for the C Minor Symphony and its completion. This was a time which was marked not only by struggles with symphonic form. The two Serenades were composed between 1857-60, and in their intimate transparent character, mark his first steps towards the large-scale orchestral compositions. The secluded, peaceful Residenz at Detmold offered the 24-year old an ideal setting for selfreflection and for concentration on smaller forms. Engaged by Princess Frederike as piano teacher and choir-master, Brahms the nature-lover found time to wander through the Teuteberg forest and think about the symphonies and divertimenti of Haydn and Mozart. Such studies inspired him to write vocal and chamber music for the "Kleine Gesangsverein" and for members of the Court Orchestra. The D Major serenade Op.ll was originally intended for solo instruments, as a nonet for strings and wind, which still adhered to the traditional form of the serenade, which was little more than a "little love song under the beloved's window". On the recommendation of Joachim, Brahms enlarged the instrumentation. Carl Bargheer, the delighted leader of the Detmold Orchestra, exclaimed that it would then be a "symphony"; but the composer denied this with the modest remark that "if one still dares to write symphonies after Beethoven, then they must look quite different". But Brahms still hankered after the larger musical form, as the two-fold character of the first serenade makes clear: while the expansive opening three movements takes up a good thirty minutes, the last three are dealt with in less than half the time. The opening reaches symphonic proportions not only because of its length; this allegro obviously inspired by Haydn's London Symphony. The serenade-like tone is set with its high spirits, and the coda makes a delightful finale in which the flute lets the main theme drift enticingly away, like a far-off wave of distant greeting. In the D Minor scherzo, the mood seems muted and curiously veiled; already, tones of the secondPiano Concerto can be heard. One expansive arch maintains the Adagio: a rocking melody begins softly, and is intricately varied by an elegaic horn melody. Brahms, however, runs out of symphonic breath in the last three movements. They are overtly serenade-like but they rush and meander along: the Menuetto with clarinets playing in sixths over the comically-plodding bassoon and the lyrical string theme: the short Scherzo with magnificent hunting-horn calls, and the gaily forwardpacing Allegro as a joyous finale. In contrast to this luminous creation in D Major, the Op.16 Serenade in A is more distinctively mellow: Brahms relinquished the sheen of the violins and used violas as the highest strings. Perhaps the overture to Mehul's opera Uthal still rang in his ears-(there, the viola is the leading instrument)-since he lets this dark timbre glow again in the first movement of his German Requiem. In the Allegro moderato (also in sonata form) bassoons and clarinets start off a chorale-like song of wonderful simplicity with delicate pizzicato accompaniment. The clarinets, always lovingly treated by Brahms, also have something to say in the second theme in the wave-like double-dotted figuration which is taken up by the strings in the recapitulation. The contrasting Scherzo is refreshingly robust with rolling 2/4 patterns over the carefree 3/4 metre. "The whole piece has something religious about it; it could be an Eleison" wrote a delighted Clara Schumann to her "dear Johannes" about the following Adagio; where, over a bass ostinato repeated eight times, rises a widely-arched wind cantilena. Interrupted by dramatic string accents in the central section, it continues throughout the whole movement, in which the Serenade becomes a notturno-passionate and intimate by turn. Already, the transparent but densely-woven golden-honed orchestral texture of the symphonic composer proclaims itself-with its balance of economy and riches, so warmly praised by Schoenberg. Echoes of the pensive mood still weave through the fourth movement, which Brahms called quasi menuetto, with good reason, since a cheerfully-paced minuet should not develop from the quiet clarinet tune and the hesitant oboe melody of the trio. Not until the Finale does a playful serenade feeling make itself clear, when even the piccolo is allowed to raise its cheeky voice. Brahms himself conducted the first performance of the Serenade Op.16 in Hamburg on 10 February 1860. How much he loved this "delicate piece"- which was always overshadowed by the sisterwork - can be seen in a letter written to the conductor Berhard Scholz, who performed the work in Breslau in 1875: "it would be really nice if you would spend some time on the Serenade and postpone the performance as long as possible, to put the players at their ease with more rehearsals" wrote Brahms who, following this with mild self-irony, notes his own "somewhat Wagnerian `tendency' to write very beautifully and lengthily about my beautiful opus." © Artists International 2001 DIRK JOERES Born in Bonn, Joeres was described by his teacher Nadia Boulanger as "a consummate musician with a charismatic presence on stage". Appearing initially as a pianist, he won first prize at the International Piano Competition in Vercelli, Italy in 1972, and notable acclaim when he took over a recital at short notice from Claudio Arrau. On the occasion of his New York debut, the New York Times characterised his "illuminating originality". His recordings have received superb reviews world-wide, with the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung highlighting his "profound insight" in both his solo and orchestral recordings. He began conducting in 1983, becoming Artistic Director of the Westdeutsche Sinfonia in 1987. When they visited the Kennedy Center, the Washington Post commented that he conducted "with authority, intelligence, and musicality." Dirk Joeres was appointed Associate conductor of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, London, at the beginning of 2000. The Orchestra's current plans together with him include a four disc Schumann Symphony Cycle coupled with largely unknown arrangements of works by Schumann.