Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

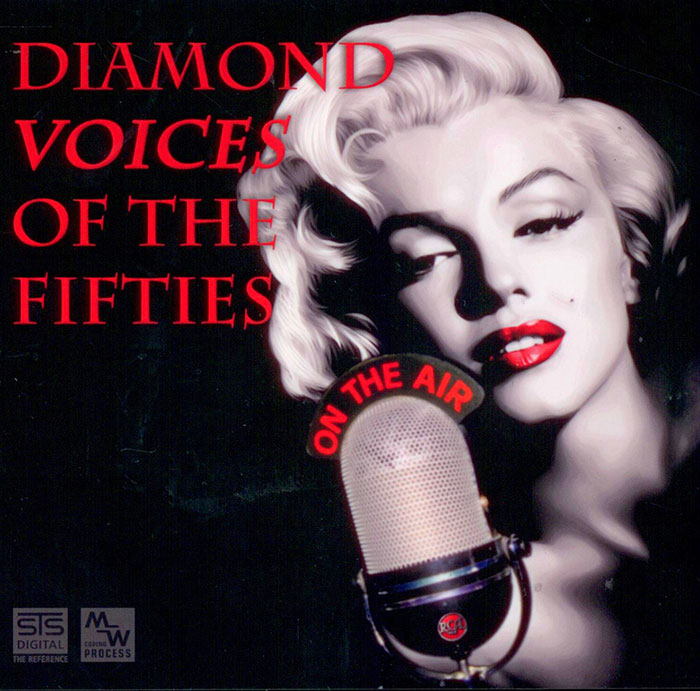

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

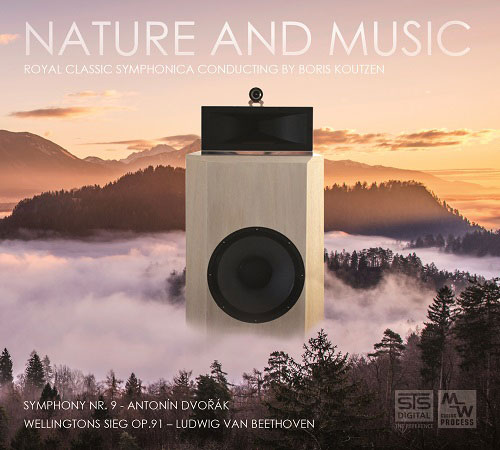

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

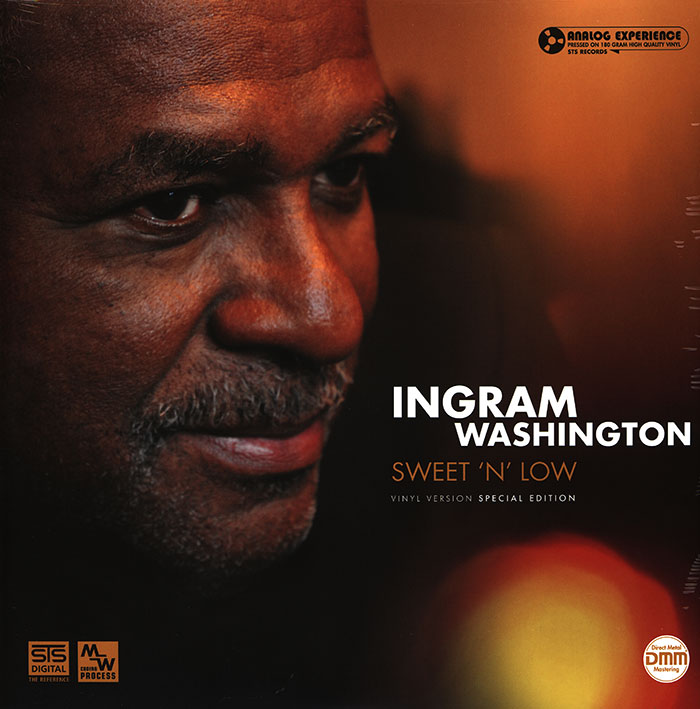

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

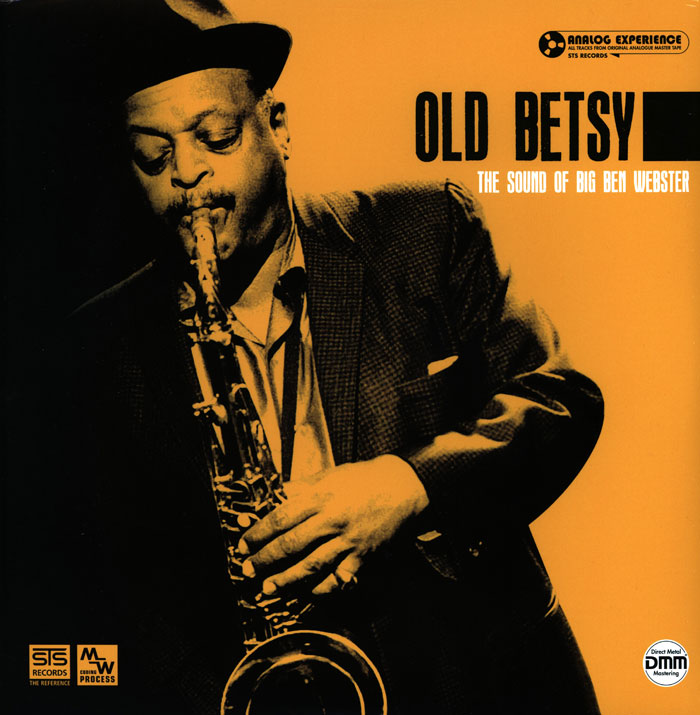

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

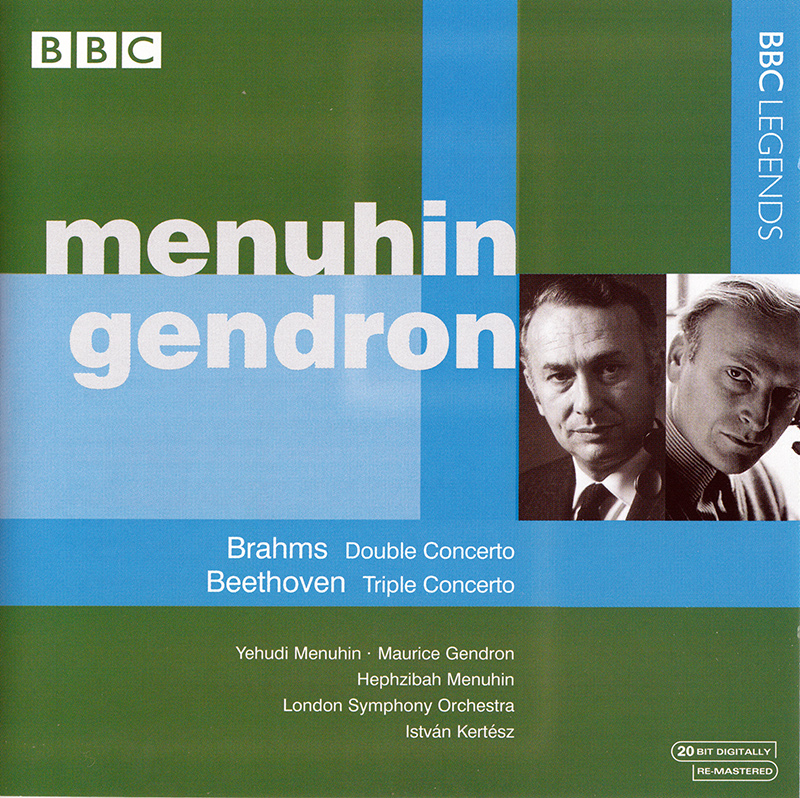

BRAHMS, BEETHOVEN, Yehudi Menuhin, Maurice Gendron, Hephzibah Menuhin, The London Symphony Orchestra, Istvan Kertesz

Double Concerto in A Minor / Triple Concerto in C Major, Op. 56

- Yehudi Menuhin - violin

- Maurice Gendron - cello

- Hephzibah Menuhin - piano

- The London Symphony Orchestra - orchestra

- Istvan Kertesz - conductor

- BRAHMS

- BEETHOVEN

A rare treat, even for the most scrupulous collectors of historical performances: the Beethoven Triple Concerto and Brahms Double Concerto with three esteemed principals and conductor, none of whom commercially inscribed the Beethoven concerto. Violinist Yehudi Menuhin (1916-1999) hardly requires another introduction; his violin tone for this 10 June 1964 concert from the Bath Festival, Colston Hall, Bristol proves deliciously, poignantly serviceable; and his colloquys with fellows Maurice Gendron (1920-1990) and sister Hephzibah Menuhin (1920-1981) move fluently and affectionately at every turn. The addition of Hungarian conductor Istvan Kertesz (1929-1973), a favorite with the London Symphony players, makes for adventurous, wholly energetic phrases rife with illuminated energy. We might recall that the Menuhin Trio (with Gendron) lasted for twenty-five years, so their innate sense of tempo and phrase has a plastic, athletic security of breath and release. The “baroque” formality of the Beethoven Triple Concerto–the cello leading every group of concertino entries–is offset by the spectacular bravura of the players’ individual prowess, supported by several blazing tuttis from Kertesz. For an immediate projection of intimate quietude, the chamber music ambiance of the Largo will long remain special to those happy collectors of this performance, whose sound from the Bristol Hall repays our audiophile sensibilities time and again. A lovely series of scales and trills lead to Gendron’s blissful statement of the Polonaise theme of the last movement; and with the two Menuhins in quick succession, we know we are in for a jolly good romp. The LSO play their often huge orchestral tissue with a decidedly warm panache, the strings and horns biting into the chords with resonant aplomb. The pomposo flair from the strings and bassoon under the sequential statements by the three soloists of the secondary, developmental theme communicates a piquant, deft charm worth the entire price of admission. Quite a subtle, flexible bow from Gendron, as his pupils–like members of the Emerson String Quartet will attest–along with Gendron’s lightning temper. The pages of the coda has the players moving in a steady flash of diaphanous runs and buzzing harmonies, a thoroughly grand and happy collaboration amongst peerless equals. The Brahms emanates a security of style and plastic sense of ensemble totally integral to the composer’s original intention to conceive a sinfonia-concertante as a reconciliation between him and the violinist Joachim. Big-toned, vibrant cadenzas alternate with virile dialogues from the principals, with Kertesz adding a sanguine, even convulsive, dimension in the orchestral utterances. The occasional, galant figure or staid march that insinuates itself into the mix alludes to the Viotti A Minor Violin Concerto. When an unkempt passage erupts out of this passionate froth, we feel the improvisational impulse at work, the searching quality on Brahms which long marked the Menuhin approach to this darkly introspective composer. The last pages of the opening Allegro movement combine as much passionate turmoil as they do sunny athleticism, always touched by the sense that Lot’s Wife ought not to be looking backwards to a more attractive past. The Andante maintains the elegiac tone in plaintive duet, the yearning after consolation, that likewise characterizes the E Minor Symphony. Kertesz lets the lower winds intrude upon the meditation, their valedictory coloring often complementing Gendron’s throaty, vocalized laments. The spirited Hungarian rondo has Gendron digging deep with his bow, matching the grueling intensity Menuhin’s idiosyncratic violin tone bestows on every bar. In three thematic groups, the movement meanders somewhat from its rustic flavor to a kind of euphoric wistfulness, only to rebound with dire punctuations from the Tragic Overture and back to the gypsy ritornello. The last pages invoke a combination of serenade and concertante swan-song whose huge, tympanic roll leads directly to an outburst of unbridled appreciation from the Bristol audience. –Gary Lemco