Logowanie

OSTATNI taki wybór na świecie

Nancy Wilson, Peggy Lee, Bobby Darin, Julie London, Dinah Washington, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls

Diamond Voices of the Fifties - vol. 2

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

DVORAK, BEETHOVEN, Boris Koutzen, Royal Classic Symphonica

Symfonie nr. 9 / Wellingtons Sieg Op.91

nowa seria: Nature and Music - nagranie w pełni analogowe

Petra Rosa, Eddie C.

Celebrating the art and spirit of music - vol. 3 - Pure

warm sophisticated voice...

Peggy Lee, Doris Day, Julie London, Dinah Shore, Dakota Station

Diamond Voices of the fifthies

Tylko 1000 egzemplarzy!!!

SAMPLER - STS DIGITAL, Buddy Tate, Milt Buckner, Walace Bishop

Jazz Masters - Legendary Jazz Recordings - v. 1

proszę pokazać mi drugą taką płytę na świecie!

Chesky! Niezmiennie perfekcyjny

Winylowy niezbędnik

ClearAudio

Double Matrix Professional - Sonic

najbardziej inteligentna i skuteczna pralka do płyt winylowych wszelkiego typu - całkowicie automatyczna

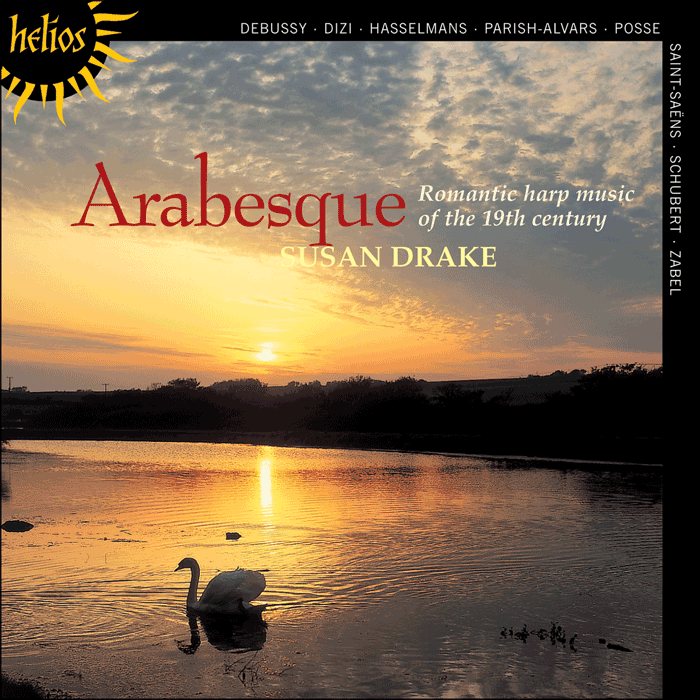

ANONYMUS, Susan Drake

Arabesque

- Arabesque No 1 Debussy [4’11]

- Will-o’-the-Wisp (Feux Follets) Hasselmans [2’26]

- Ar hyd y nos (All through the night) arr Drake [3’14]

- Romance in G flat major Op 48 No 3 Parish-Alvars [2’41]

- La Mandoline Op 84 Parish-Alvars [6’40]

- Ave Maria Schubert, arr Thomas [6’20]

- La fille aux cheveux de lin Debussy [2’33]

- Am Springbrunnen Op 23 Zabel [5’02]

- Variations on ‘The Carnival of Venice’ Posse [10’58]

- Romance (Jeux Interdits) anonymous, arr Drake [2’15]

- Etude No 21 (Allegro espressivo) Dizi [3’15]

- Marguerite douloureuse au rouet Op 26 Zabel [3’33]

- Le Cygne (The Swan) Saint-Saens, arr Hasselmans [2’17]

- Susan Drake - harp

- ANONYMUS

Romantic harp music of the 10th Century

'Will give much pleasure to harpists, day-dreamers, and the good old-fashioned romantics in our midst' (Gramophone)

---------------------------------------------

This recording presents a programme of romantic music, virtually unknown except to its performers, for perhaps the most romantic of all instruments—the harp. The ancestors of the instrument stretch long back into antiquity. Its forbear the lyre, for instance, can be seen among the stone paintings of ancient Egypt and on Greek earthenware from 2000BC, and there are references to it in the Bible (‘Praise the Lord with harp’—Psalm 33).

The simplicity of those early harps, though, has long since been left behind and their modern descendent is a very complex instrument indeed. The note given out by a vibrating string, on whatever instrument, is governed by its length: the longer the string, the lower the note. Clearly, then, a string of fixed length has to be shortened, or ‘stopped’, to change its note to a higher pitch. On the violin, cello or guitar, for instance, this is done by using the fingers to depress the string on to the neck or fretboard, and all that is required is a high degree of finger agility to play these instruments in a variety of keys, modulating from one to another with the highest speed. This, however, cannot be done on the harp for two main reasons: there is no fretboard to provide support, and in any case its player needs both hands to pluck the strings.

This limitation was solved in the nineteenth century with the invention of the pedal harp. The modern harpist, like the organist, now needs agile feet as well as hands, since the body of the instrument hides a complicated mechanism of levers, operated by pedals, which enables the player to alter the pitch of the strings and thereby play and modulate in a variety of keys previously inaccessible to it. The invention of this sophisticated instrument enabled composers to write music of much more colour and variety, and on this record will be found part of the subsequent legacy of music from the richest period of the harp’s history, the nineteenth century. Like other instruments, the harp had, and has, its share of virtuoso performers, many of them writing prolifically for it.

Alphonse Hasselmans was born in Liège, Belgium, in 1845 and studied in Strasbourg, Germany, with Gottlieb Krüger who himself had been a student of Parish-Alvars (see below). In 1884 he became professor of harp at the Paris Conservatoire, a position which he held until his death in 1912. Hasselmans played a major role in the revival of interest in harp-playing towards the end of the nineteenth century. A good many compositions by other composers were inspired by his virtuoso playing and were dedicated to him, among them being Fauré’s Impromptu, Op 86. Hasselmans himself did not attach much importance to his own compositions but his charming salon pieces added greatly to the harp’s repertoire, not least in their technical value.

Elias Parish-Alvars was born in Teignmouth, Devon, in 1808 and studied the harp with Theodore Labarre, François Dizi and Robert Bochsa before becoming the most celebrated performer of his day. He was greatly admired by Mendelssohn, and by Berlioz who called him ‘The Liszt of the harp’. He toured Europe from 1831 to 1836 and the near East from 1838 to 1841. His compositions include many of the national melodies of the countries he visited. He is reputed to have had a formidable technique (it is said that he played at sight, on the harp, the Chopin piano sonatas and the Beethoven and Hummel concertos) and many of his pieces must be among the most demanding in the harp’s literature. He was appointed chamber harpist to the Emperor of Austria in 1847 but died in Vienna only two years later of consumption.

The Grand Study in imitation of the mandoline was composed late in 1844 or early 1845, inspired by his visit to Naples. The Romance in G flat major, one of a set of pieces published as Op 48, is preceded by a few lines from Lord Byron:

It was enough for me to be

so near, to hear and—oh! to see

The being whom I loved the most.

John Thomas was born in Bridgend, South Wales, in 1826. At the age of eleven he won a harp at a national Eisteddfod and three years later, in 1840, Lord Byron’s daughter Ada, the Countess of Lovelace, sent him to the Royal Academy of Music in London, where he studied the instrument with J B Chatterton. In 1851 he played in the orchestra of the Opera and made the first of many tours of Europe, continued over the next fifty years. In addition to many appearances throughout Britain and the continent, he also adjudicated regularly at his native Welsh Eisteddfodau. On July 4, 1862, he gave a concert of Welsh music at St James’s Hall, London, with a chorus of four hundred, and twenty harps. Among his numerous compositions for harp, both solo and concerto, he published a collection of Welsh melodies and arrangements of Schubert songs and Mendelssohn’s ‘Songs Without Words’. Although he played the pedal harp rather than the triple-strung Welsh harp, he was given the bardic name of ‘Pencerdd Gwalia’—Chief Musician of Wales—in 1861. In 1872 he became harpist to Queen Victoria. He died in London in 1913.

Albert Zabel was born in Berlin in 1834. Through a scholarship obtained for him by Meyerbeer, he studied at the Berlin Institut fur Kirchenmusik where his harp teacher was Louis Grimm. From the age of eleven he toured for three years with Gungl’s band, travelling to Russia, England and the United States. At fourteen he was appointed solo harpist to the Berlin Opera and in 1855 he moved to St Petersburg to become solo harpist with the Imperial Ballet, remaining there for the rest of his life. In 1862 Anton Rubinstein founded the St Petersburg Conservatory and appointed Zabel as teacher of the harp. He became professor in 1879 and, subsequently, honorary distinguished professor in 1904. He died in 1910 in St Petersburg.

Zabel left a sizeable number of compositions for the harp, including a concerto in C minor, Op 35. Am Springbrunnen, or La Source as it is often called, is probably his most famous composition for the harp.

Franz Liszt considered Wilhelm Posse the greatest harpist after Parish-Alvars, and consulted him on the harp parts of his later orchestral works. He was born in Bromberg in 1852 and, after early musical training from his father, taught himself to play the harp. At the age of eight he appeared at the Italian Opera in Berlin accompanying Adelina Patti. He was solo harpist with the Berlin Philharmonic and Berlin Opera from 1872 to 1903, and taught at the Charlottenburger Hochschule in Berlin from 1890 to 1923, becoming ‘Royal Professor’ in 1910. He died in Berlin in 1925.

François Joseph Dizi was born in Namur, South Netherlands, in 1780, the son of a music teacher from whom he received his earliest musical training. He taught himself the harp and came to England at the age of sixteen to improve his technique. (He lost all his money and possessions on the way. Whilst his ship was in harbour he dived overboard to rescue a sailor who had fallen into the water; the ship went on without him, taking all his belongings.) Unable to speak English, and penniless, he somehow found his way to the London home of the famed maker of pianos and harps, Sebastian Erard. This led to an introduction to Clementi who, recognising his talent, helped him to establish himself. Before long he was regarded as the most renowned harpist in England, a reputation which he maintained for thirty years. Among his many pupils was Parish-Alvars.

Dizi left London in 1830 to join the firm of Pleyel in Paris with the intention of founding an establishment for the manufacture of harps. But this came to nothing. He died in Paris some time around 1840.

Of his various compositions for the harp, the 48 studies are considered the most important, being melodious and technically valuable. One of these, number 21, is included here.

Perhaps looking slightly out of place among these prominent harp musicians of the nineteenth century is Claude Debussy, since he is acknowledged to be among the most original and influential composers of the twentieth. He was, however, born long before the new century, in 1862, and wrote much music before 1900. The Arabesque is the first of two written for piano in 1888/9, but it sounds equally well on the harp without any sort of arranging. La fille aux cheveux de lin (The girl with the flaxen hair), though, is very much of the twentieth century, coming as it does from the first book of Preludes for piano, written in 1910. But it is a charming and endearing piece, and again transfers well and without alteration to the harp. Perhaps one can excuse its inclusion in a programme of nineteenth-century harp music on the grounds that without the championship of the harp by the other composers on the record, and their influence on harp construction and playing technique, it could not be heard in this very attractive form.

Susan Drake © 1983